A career spent chasing down polio

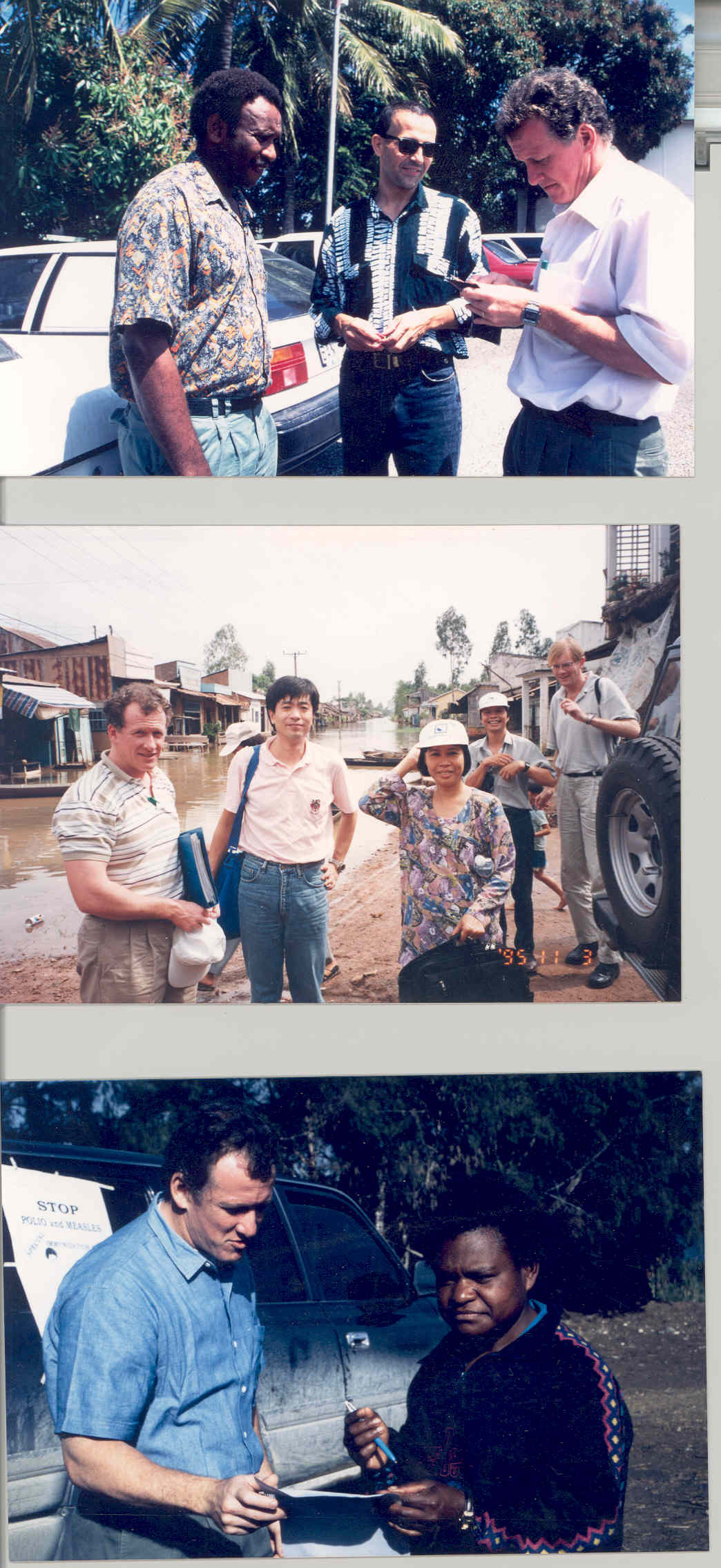

Meet WHO’s Chris Maher, who has spent 25 years following polio to its last hiding places.

After more than 25 years on the hunt for polio, it’s easier to list the things the World Health Organization’s Chris Maher hasn’t seen than the things he has. He began his career with WHO five years after the global health community vowed to eradicate polio, which was then found in over a hundred countries. Since then, Maher has progressed to spearhead on-the-ground operations for the global polio eradication initiative, a partnership that has seen the disease beaten back by 99%. In a ceremony in May 2018, the Australian Government awarded him the Order of Australia, recognizing his immense contributions to the fight against a disease that has gone from paralyzing more than 350 000 children every year in 1988, to fewer than 22 cases worldwide today.

In 1993, Maher had several years of experience in public health, but none in polio-endemic countries. “I don’t think I’d ever seen an active polio case,” he recalled. Upon joining the WHO immunization team in a region that spanned from Mongolia to the Pacific Islands, polio was suddenly at the top of his agenda.

Maher and his colleagues worked as disease detectives, stalking the wild poliovirus through hard-to-reach communities in south-east Asia. From immunizing small communities on the Pacific Islands to taking on massive campaigns targeting millions of children in China, the complexity made his head spin.

The Philippines was the first country to go polio-free on Maher’s watch, seeing its last case that year.

Tracking unimmunized children through a population maze

It was here that Maher came face to face with polio’s full force of devastation, after a Khmer nurse at a district health clinic invited him home to meet her son. Maher and a colleague followed the woman to a house on stilts in a flooded field, where a quadriplegic teenager lay on a rattan bed.

“I realized very early on, he had polio. It was typical of the kind of polio that had no rehabilitation whatsoever”, Maher said.

Maher recalls being struck by the young man’s intelligence and his interest in the world, despite his isolation. As polio destroyed his body, his mother bestowed constant care.

“While she was working every day, somehow she had managed to look after him, to provide for him. As an example of motherly love I had never seen anything like that in my life.”

By the 2000s, it seemed that the most challenging country to eradicate polio was India. With its vast population and sprawling slums, in Maher’s words, “If technically we couldn’t do it, India would be the place we’d fail.”

Maher recalls Bihar, India as “the most extraordinary place that I ever worked on polio.” Eighty million people live in the state. Widespread illiteracy, a lack of infrastructure and high levels of population movement compounded the complexity of polio eradication there.

Despite the daunting challenges, Maher and his colleagues developed systematic plans to administer vaccine to all children across the country, taking a critical step in a journey to eradication. By the end of 2011, India was polio-free.

The risk of doing something different

At the start of the global push to eradicate polio, those involved in the operation would sometimes encounter skepticism from those who thought it simply couldn’t be done. The scale of the project, the size of activities and the time, energy, effort and cost involved had never been seen before.

Today, wild polio is endemic in three countries: Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria. Immense efforts to battle the virus into extinction in these places are ongoing. Outbreaks of vaccine-derived polio virus (VDPV) add complexity to the end goal. Conflict, low routine immunization and population movement in the most at-risk areas complicate things further. Some of the approaches Maher and his eradication colleagues take to navigate these and myriad other challenges are astonishing – feats of logistics, diplomacy and detection that would not be out of place in a textbook.

“We’ve learned a lot about reaching every community, the most difficult access places, we’ve learned a lot about the importance about communicating what we are trying to achieve, to bring communities along with us in what we were doing. We’ve learned that there are certain things that are too big to do yourself. You need to build coalitions, you need partnerships to be able to make something happen, and the broader that partnership is, the greater the likelihood that you are going to be able to achieve something significant,” he said.

For Maher, the real risk is not that polio won’t be defeated, but that the world might one day forget how it was done. He sees the lessons learned during eradication as critical to the global health community.

“It would be a terrible pity if we lost that, if after eradication we kind of collectively heaved a sigh of relief and said, ‘well thank goodness that’s over, let’s do something else now’.”