News Category: Vaccination campaigns

The first of four large-scale immunization campaigns is set to kick off in Papua New Guinea next week, following last month’s confirmation of a circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1 (cVDPV1). More than 2900 health workers, vaccinators and volunteers have been mobilized to vaccinate almost 300 000 children under 5 years of age in Morobe, Madang and Eastern Highlands provinces. The campaign from 16-29 July is the first in a series of vital immunization campaigns planned every month for the next four months.

“Polio is back in Papua New Guinea and all un-immunized children are at risk,” said Pascoe Kase, Secretary of the National Department of Health (NDOH). “It is critical that every child under five years of age in Morobe, Madang and Eastern Highlands receives the polio vaccine during this and other immunization campaigns, until the country is polio-free again.”

As polio is a highly infectious disease which transmits rapidly, there is potential for the outbreak to spread to other children across the country, or even into neighbouring countries, unless swift action is taken. With no cure for polio, organisers of the immunization drive are calling for the full support of all sectors of society to ensure every child is protected. Parents living in the three provinces are encouraged to bring their children to local health centres or vaccination posts to receive the vaccine, free of charge, during the campaign.

“Everyone has a role to play in stopping this terrible disease,” commented Dr Luo Dapeng, WHO Representative in Papua New Guinea. “We call on parents to bring your children under five years of age for vaccination, irrespective of previous immunization status. Together, we can help ensure that this outbreak is rapidly stopped and that no further children are paralysed by polio.”

The Officer In Charge for UNICEF Representative, Ms. Judith Bruno, stressed, “As long as the polio virus persists anywhere, all un-immunized children remain at risk, and since polio carries enormous social costs, we must make it a key priority to stop its transmission so that children, families and communities are protected against this terrible disease.”

The immunization campaign is organized by the National Department of Health and the Provincial Health Authorities, with support from the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, Rotary International and other partners.

Campaign dates are:

• First Round: 16-29 July 2018

• Second Round: 13-26 August 2018

• Third Round: 10-23 September 2018

• Fourth Round: 8-21 October 2018

Following confirmation of the cVDPV1, on 22 June the National Department of Health of Papua New Guinea immediately declared the outbreak a ‘national public health emergency’, requiring emergency measures to urgently stop it and prevent further children from lifelong polio paralysis. The measures implemented by the government intend to comply fully with the temporary recommendations issued under the International Health Regulations ‘Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC)’.

Papua New Guinea has not had a case of wild poliovirus since 1996, and the country was certified as polio-free in 2000 along with the rest of the WHO Western Pacific Region. In Morobe Province, polio vaccine coverage is suboptimal, with only 61% of children having received the recommended three doses of polio vaccine. Water, sanitation and hygiene are also challenges in the area, which could contribute to further spread of the virus.

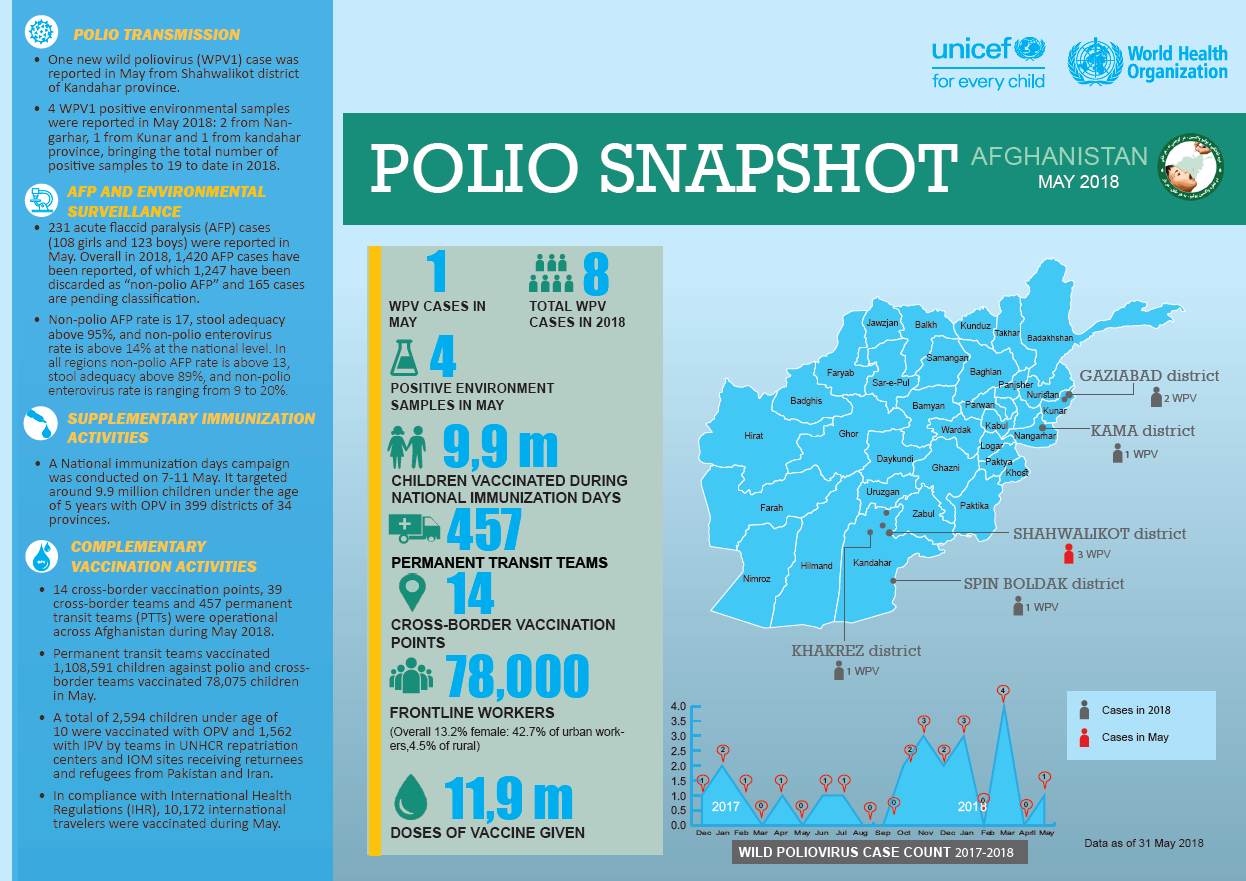

In May:

- There was one new case of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1).

- 9.9 million children under five years of age were targeted during national immunization days in 399 districts of 34 provinces.

- Permanent transit teams successfully vaccinated 1 108 591 children against polio, whilst cross-border teams vaccinated 78 075 children.

For full update please click on pdf below.

The environment

Dar es Salam refugee camp, in Bagassola district, Chad, is home to thousands of refugees. 95% of the population is Nigerian, displaced by years of violent insurgency, drought and insecurity in the Lake Chad basin. Some have lived in the camp since 2014.

Here, temperatures soar to 45 degree Celsius nearly every day. Dust is inescapable, colouring everything a shade of yellow. Houses are constructed from tents, tarpaulins and reeds, pitched onto sand. There is no employment, few shops, and no green areas.

Kilometers from the lake, residents have no access to the water around which their livelihoods revolved, as fishing people, as traders at the markets located around the island network, or as cattle farmers. This renders them almost entirely reliant on aid. The edge of the camp is an enormous parking lot, filled with trucks loaded with donations. Signs interrupt the landscape, attributing the camp’s schools, football pitches, and water stations to different funding sources.

Polio immunization is a core health intervention offered by the health centre here, with monthly house to house vaccination protecting every child from the virus.

“We vaccinate to keep them healthy”

In return for their work, vaccinators receive a small payment, one of the few ways of earning money in the camp. In Dar es Salam, there are thirty positions, currently filled by 24 men and six women, and applications are very competitive. Those chosen for the role are talented vaccinators, who really know their community.

Laurence speaks multiple languages, adeptly communicating with virtually everyone in the camp. He is a fatherly figure, engaging parents in conversations about the importance of vaccination whilst his colleague gives vaccine drops to siblings. Their mother is a seamstress, constructing garments on a table under one of the few leafy trees. Laurence engages her in conversation, explaining why the polio vaccine is so important.

Describing his work, he says, “I tell parents that the vaccine protects children from disease, especially in this sun, and that we vaccinate every month to keep them healthy.”

A precious document in a plastic bag

Chadian nationals living in nearby internally displaced persons camps don’t have the same entitlements as international refugees. Several hours’ drive from Dar es Salam, children lack access to even a basic health centre.

At a camp in Mélea, vaccinators perform routine immunization against measles and other diseases under a shelter made from branches. Cross-legged on the ground, they fill in paperwork, carefully administer injections, sooth babies, and dispose safely of needles. Other vaccinators give the oral polio vaccine to every child under the age of ten. These children are mostly from the islands, displaced by insurgency. Their vaccination history is patchy at best, and it is critical that they are protected.

One father arrives accompanied by his small, bouncy son. As the baby looks curiously at the scene in front of him, his dad draws out a tied plastic bag. Within is his son’s vaccination card, carefully protected from the temperatures and difficult physical environment of the camp.

A UNICEF health worker reads it, and realizes that the child is due another dose of polio vaccine. Squealing with confusion, the baby is laid back in his sibling’s arms, and two drops administered. The shock over, he is quickly back to smiling, rocked up and down as his dad folds up the card, and ties it up in the bag once more.

“Our biggest challenge”

Back in Dar es Salam, DJórané Celestin, the responsible officer for the health centre explains the wider challenges of vaccination in this environment.

“We don’t just vaccinate within Dar es Salam in our campaigns. We are also responsible for 27 villages in the nearby surroundings. Reaching these places proves our biggest challenge.”

Away from the main route to Dar es Salam, there are no roads or signs, and many tracks are unpassable. To reach the 539 children known to live in the villages, vaccinators walk, or rent motorbikes, travelling for many hours.

This month, another round of vaccination in the Lake Chad island region concluded. Hundreds more refugee and internally displaced children are protected, in some of the most challenging and under-resourced places to grow up.

Three-year-old Ibrahim wouldn’t stop crying. Suffering from ringworm, a fungal infection, his leg had become badly infected. Left untreated, he risked developing fever and scarring wounds.

For Ali Musa, his father, it was hard to know where to turn for help. Where he lives, in the nomadic community of Daurawa Shazagi in the Nigerian state of Jigawa, there is little access to professional medical treatment.

From his home, it would take Ali a full day to trek to the nearest primary health centre. He does not recall the last time anyone in his community made this “practically unthinkable” journey.

Reaching all children with vaccines

“But when I heard in the market that a medical team was coming to us to treat sick people, especially women and children, I went with the hope to at least get him some relief from the pain,” Ali recalls.

There, Ali met members of the mobile health teams supported by the UNICEF Hard-to-Reach (HTR) project – funded by the Government of Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development. These teams are helping to ensure that children receive polio vaccinations, whilst also providing basic health services – including medications to fight infections like ringworm – in hard-to-reach areas of Nigeria.

The teams vaccinate against measles, meningitis and other diseases, and provide vitamin A supplements and deworming tablets for children. They also carry out health promotion activities, teaching communities about important practices such as exclusive breastfeeding. During each clinic, members of the HTR team give two drops of polio vaccine to every child, ensuring that all are protected from the virus.

At the end of their visit, the team pack up the clinic, and travel home, taking hours to cross difficult terrain by foot, boat and motorbike.

2390 children vaccinated

The HTR project aims to reduce the immunity gap among children living in Nigeria. Since 2016, when cases of wild poliovirus last were detected in the country, determination and commitment have helped to strengthen eradication efforts, but many states still face an uphill task to increase historically low routine immunization rates. This is especially the case in rural areas, where there are few services, and communities have to travel far to the nearest health clinic.

So far in 2018, the project has reached thousands of previously unvaccinated children with the life-saving polio vaccine, including 2390 children in Ibrahim’s state, Jigawa.

“Why should I let anything stop me?”

Salamatu Kabir, who leads a HTR team assigned to take immunization and basic health care services across Jigawa, says “I look at it this way. If people from outside can come all the way to bring the hard-to-reach project to my country, why should I let anything stop me from delivering it to my own people who are most in need?”

A retired health worker, she says that she doesn’t think twice about the many hurdles that she will have to overcome to reach children in communities like Ali and Ibrahim’s.

Far more of a concern is planning meals for her four children whilst she is away, and packing all the equipment she will need for the journey. Experience over the years has taught her what items to add to her bag besides vaccines. She always carries an umbrella, an extra pair of clothes, insect repellant and depending on the season, either an additional pair of sandals or, most often, rain boots.

Salamatu asserts that for the team members, “visiting the settlements to administer health care is something we have come to love and look forward to”.

When the team finally does arrive at their destination they are greeted by an expectant community. Salamatu is motivated by the direct impact her work has on the lives of others.

Little Ibrahim is one of those to benefit. After treatment from the team, his condition improved quickly. His father Ali has since become a volunteer for the HTR project, and an avid advocate within his community for medical care.

“I will do my best to ensure every child in my village benefits from the help that is coming from far,” he says.

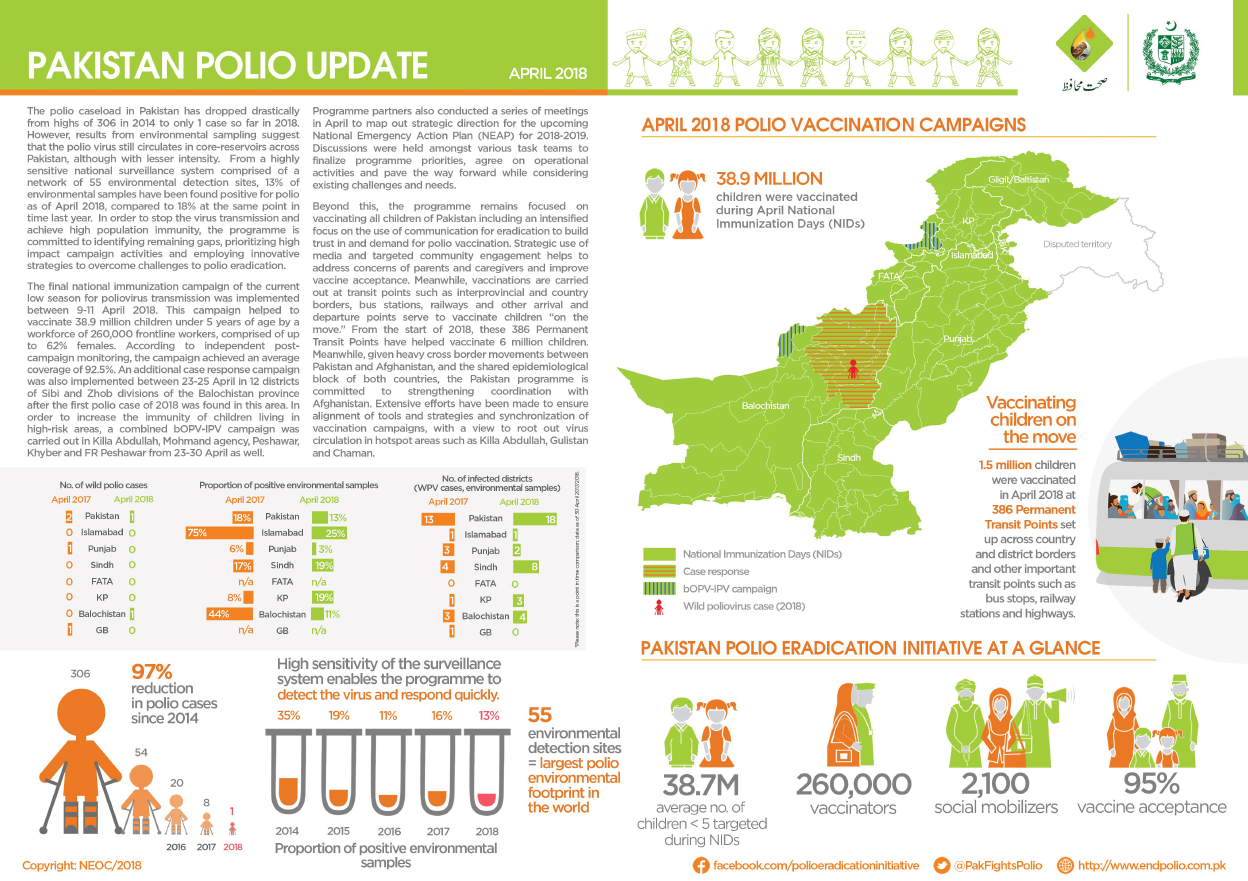

In April:

- No new cases of poliovirus (WPV1) were reported.

- 38.9 million children were vaccinated against poliovirus by a team of 260 000 dedicated frontline workers.

- Teams at transit points and borders successfully vaccinated 1.5 million children.

For full update please click on pdf below.

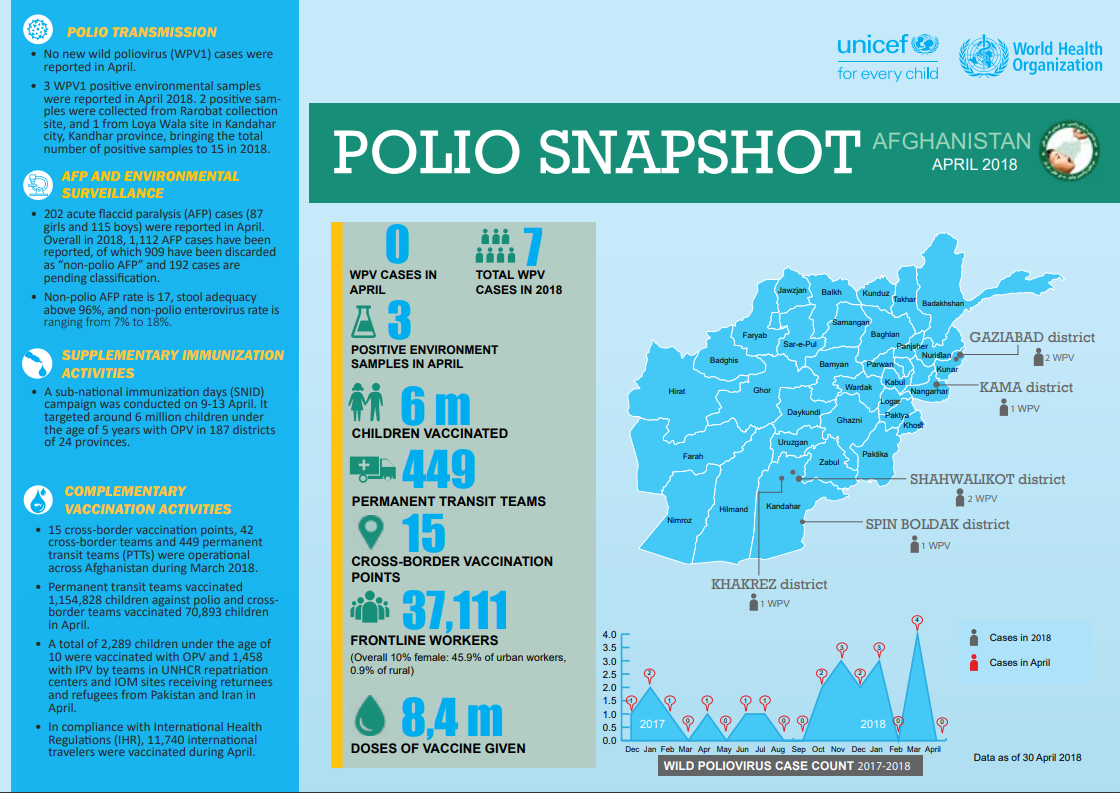

In April:

- No new cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) were reported.

- 6 million children under five years of age were targeted during sub-national immunization days in 187 districts of 24 provinces.

- Permanent transit teams successfully vaccinated 1 154 828 children against polio, whilst cross-border teams vaccinated 70 893 children.

For full update please click on pdf below.

Almost everyone in the Killa Saifullah district of Balochistan, Pakistan, knows and respects 35-year-old Taj Muhammad. A dedicated and passionate doctor by profession, Dr Taj spends his days working as a Union Council Medical Officer in his local public health facility, and his evenings running a free medical clinic for local residents.

In his capacity as Medical Officer, he coordinates polio eradication efforts at the Union Council level, which is the smallest administrative unit in Pakistan.

His role includes coordinating microplanning, training frontline health workers, and supervising polio vaccination campaign activities. Since the start of his medical career in 2007, he has supervised more than 100 polio vaccination campaigns.

Dr Taj says he became a doctor to fill the existing health care gap in his area. “During my childhood, my mother was seriously ill and she died because of the absence of medical facilities in our area. She often used to tell me that I must become a doctor to help poor people with their health. She died afterwards but her words are still in my heart,” he explains.

His hometown, Killa Saifullah, is located 135 kilometers away from Balochistan’s provincial capital Quetta. Economic and social deprivation is widespread, and the district lacks basic health facilities, particularly for women and children. “There is only one hospital, serving only 150 people per day in the district, whereas the current population is more than 200,000. In these conditions, working as a medical officer is quite challenging,” Dr Taj says.

His job is tiring, and the demands are huge, but Dr Taj perseveres. As well as supporting polio vaccination activities, and endorsing vaccination, each day he tends to the large crowd of people who gather outside his evening clinic, often desperately needing health care.

His work to serve his community is particularly important because Killa Saifullah lies close to Dukki, where the only case of polio in Pakistan so far in 2018 was reported. Nawabzada Dara Khan, who chairs the Killa Saifullah’s Municipal Committee, notes that the community feels “vulnerable” knowing that the virus is close by.

Since the first polio case of 2018 was detected, polio vaccination campaigns have been conducted in response in all neighboring districts, including Killa Saifullah. But whilst this has increased immunity to the virus, it has also caused vaccine hesitancy amongst some parents, who question the need for multiple vaccination campaigns.

“We are trying hard to vaccinate each and every child; however, repeated campaigns and misconceptions are posing a big challenge for us,” Dara Khan says.

Luckily, the efforts of dedicated doctors like Dr Taj are helping to remove misconceptions and doubt. With the immense trust and respect he enjoys from his community, he has been able to use his free evening clinic as a local platform to advocate for polio eradication and the safety of the vaccine, extending his critical role in the polio programme.

Dara Khan adds, “The contribution of Dr Taj in polio eradication is commendable. His goodwill is playing a very positive role within our community to remove these misconceptions.”

His impact is also wide ranging, reaching multiple different families.

The proof? In April, thanks to the intensive efforts of Dr Taj and others, no parents or caregivers in Killa Saifullah refused vaccination.

That’s 70,690 children who now have lifelong protection from polio.

How do vaccinators ensure that every child is reached?

Every child needs to be vaccinated to protect them from poliovirus. To achieve this, detailed plans are prepared for vaccination teams. The aim is to find each child under 5 years of age – in Afghanistan, that’s around 10 million – and to reach them with vaccines.

A heavy steel gate opens on a quiet suburban street in central Herat. The city lies in a fertile river valley in Afghanistan’s west, an area rich with history. Over the centuries, invaders from Genghis Khan’s army to the troops of the Timurid empire, the Mughals and the Safavids have opened the gates to rule the city once known as the Pearl of Khorasan.

Now, a far more peaceful group can be seen walking down the streets of Herat. Equipped with blue vaccine carrier boxes and drops of polio vaccine, the teams knock on one door after another to vaccinate any children they find inside. The aim is to eradicate polio in Afghanistan.

Four-year old girl Fariba peeks from behind the gate and steps out on the street, followed by her father Mashal.

Mashal encourages his daughter to open her mouth to receive two drops of polio vaccine, and a drop of vitamin A. Fariba looks at the vaccinators with suspicion, but follows her father’s guidance.

The vaccinators thank them and continue down the street.

Locating all children

In March, vaccinators in Herat gave oral polio drops to over 150 000 children.

In a country with one of the highest rates of population growth in the world and frequent population movement, it is no easy feat to tell how many children live in each province, district, village, block, house or tent.

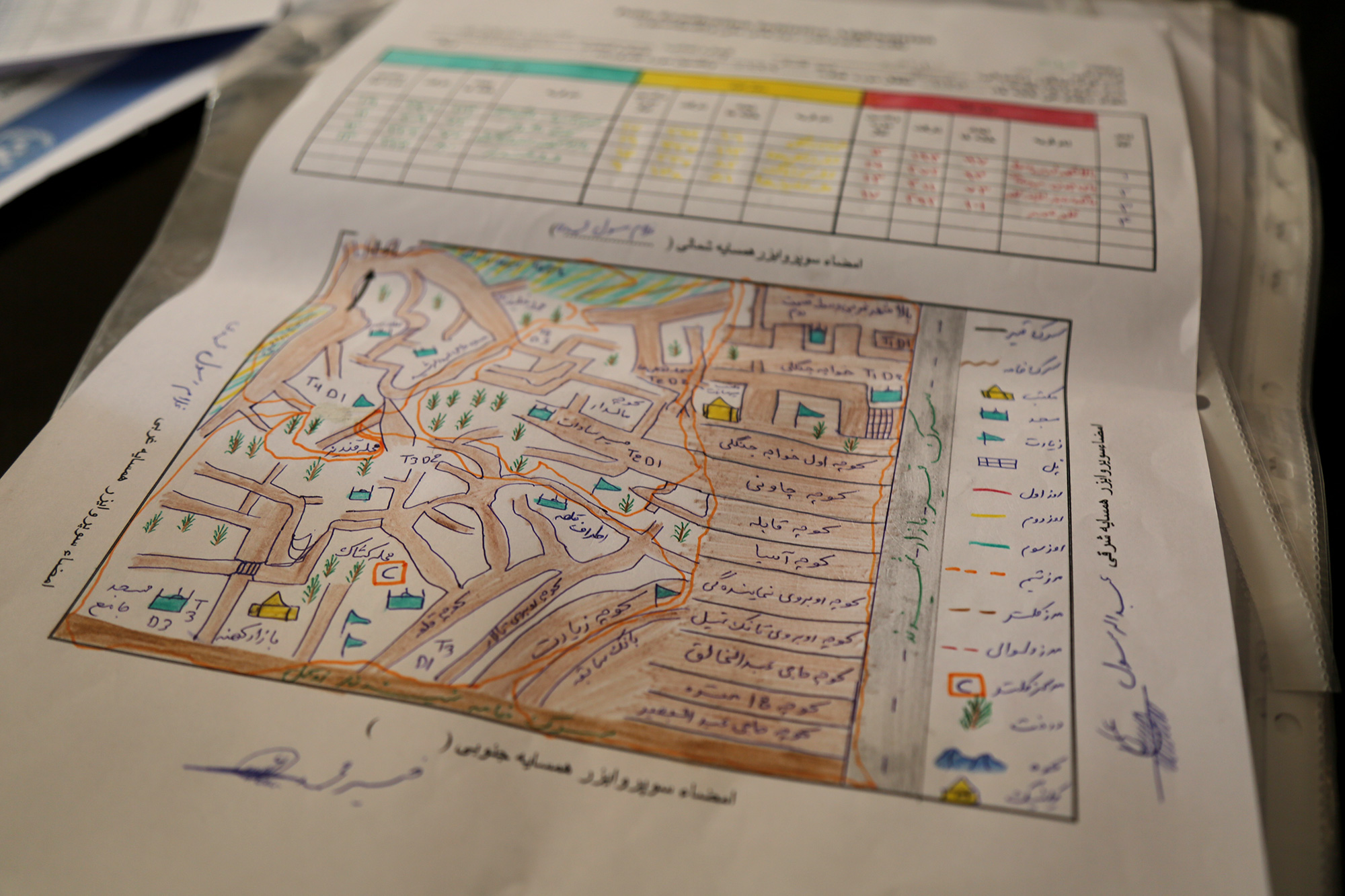

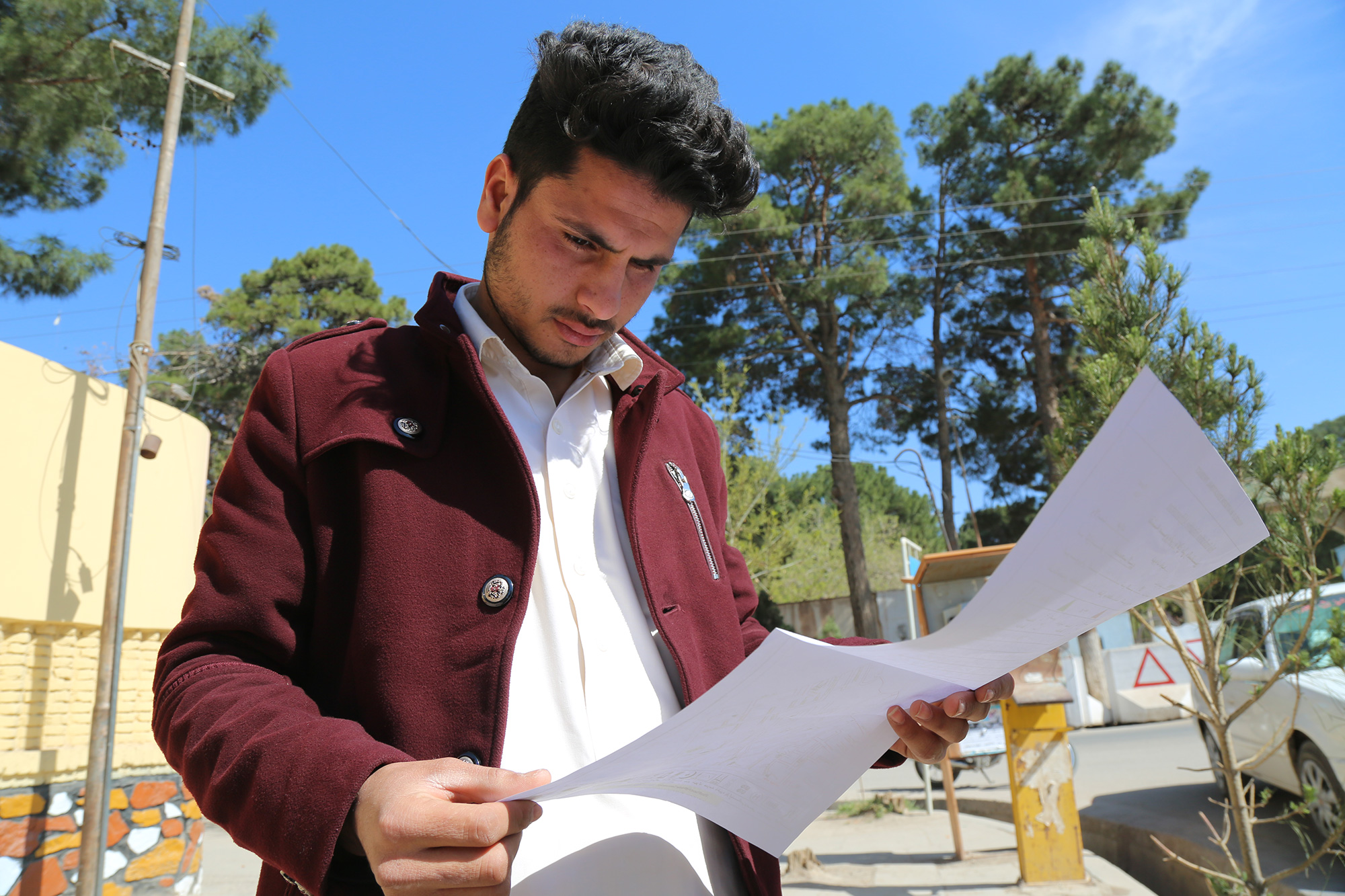

How do vaccinators know where the children in each area are located then? Through a simple but elegant guide known as a ‘microplan’. This is what the vaccinator follows: Where to start the day, how many children live on that street, which is the next house to visit?

No coincidence: Who goes where

A few kilometres from Fariba and Malik’s home, Dr Khushal Khan Zaman is sifting through printed plans on his desk at the World Health Organization office.

Dr Khushal explains that once a year, health workers physically count the houses in their area. Then they check that the plans from the previous year still match the numbers.

Campaign supervisors know the approximate number of children in each house from the last campaign. But the data is complemented by their personal knowledge. As locals, they often know of any changes in the composition of their community – where new children have been born, or the location of nomadic groups who have settled in the area.

This helps keep the plans accurate. For instance, if a nomadic group has stayed in an area for a longer time, their tents may be added to the microplans. For shorter stays, a separate checklist is used instead to monitor nomadic population movement. This improves the programme’s ability to trace and reach every child with vaccines, even if they are on the move.

Once the plans have been updated, teams of vaccinators are assigned to visit specific homes on a particular day during the upcoming campaign.

The final plan indicates not only the numbers of houses and children, but also details on how many related items are needed for each team: vaccine vials, vaccine carriers, ice packs (to keep the vaccines at optimum temperature), chalk, tally sheets, pens, leaflets, finger markers, plastic bags and scissors.

This is a contrast to a few years ago, when the plans listed only the name of the area with the estimated number of children to be vaccinated. The newer plans include even the smallest houses, and information on the closest mosque and local elders.

“It needs to be clear to everyone, which team is responsible for which area. We mark where the teams start and which direction they take using arrows,” Dr Khushal explains.

And it is no coincidence who goes where. To ensure that parents allow their children to be vaccinated, vaccinators may be allocated parts of their community that they know well, to increase trust when they deliver the vaccine.

Children like Fariba might not understand yet why the vaccine is important, but their father does. When vaccinators knock, it is not chance that brings them, but care and commitment.

For 15 years Daeng Xayaseng has been travelling through rugged, undulating countryside by motorbike and by foot to deliver vaccines to children in some of the most remote villages in Laos.

It’s hard work but she is determined: “We have a target of children to reach and we’ll achieve that no matter how long it takes,” she says. “We’ll keep working until we reach every child.”

Today her team visits Nampoung village, 4 hours north of the capital of Laos, to deliver polio vaccines.

“For 15 years I’ve been working on campaigns like this,” she says. “Today we’re here with our outreach team to vaccinate children against polio. We’ll also go house to house to make sure no child misses out on being vaccinated.”

“We don’t want there to be another outbreak of polio so we have to reach everyone,” says Daeng. “In order to do that, immunizing every child in remote communities like this is a priority to ensure everyone is protected.”

UNICEF and other partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative are supporting the Lao Government to reach nearly half a million children under five with potentially life-saving vaccines. More than 7,200 volunteers and 1,400 health workers like Daeng and her team have been mobilized to deliver the oral polio vaccine as well as other vaccinations such as measles-rubella.

“I’m very happy and proud to do this job,” says Daeng once the team has packed up. “I’m proud to do this job to serve the community and help in any way I can.”

Read more:

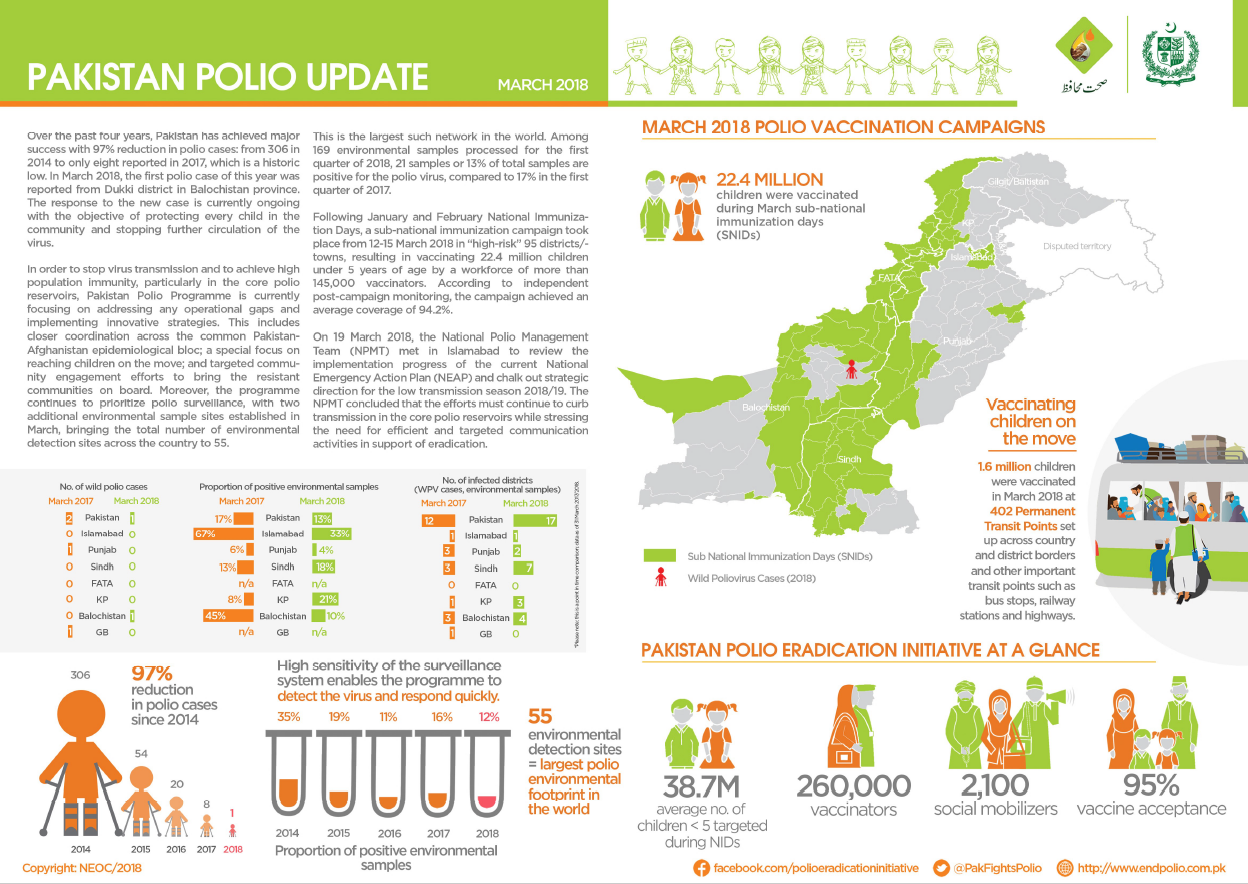

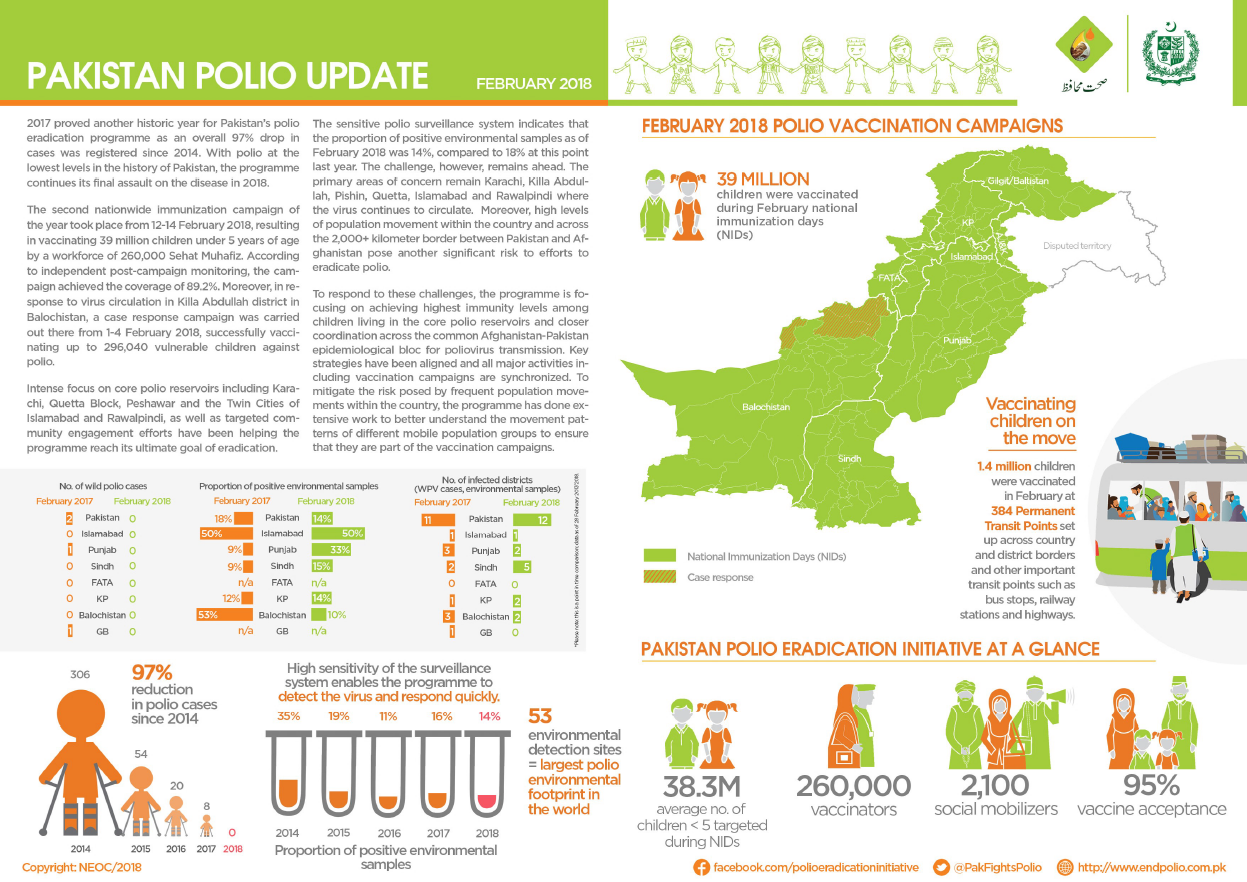

The Pakistan polio snapshot gives a monthly update on key information and activities of the polio eradication initiative in Pakistan.

In March:

- One new case of wild poliovirus (WPV1) was detected.

- 4 million children were vaccinated against poliovirus by a team of almost 260 000 dedicated frontline workers.

- Teams at transit points and borders successfully vaccinated 1.6 million children.

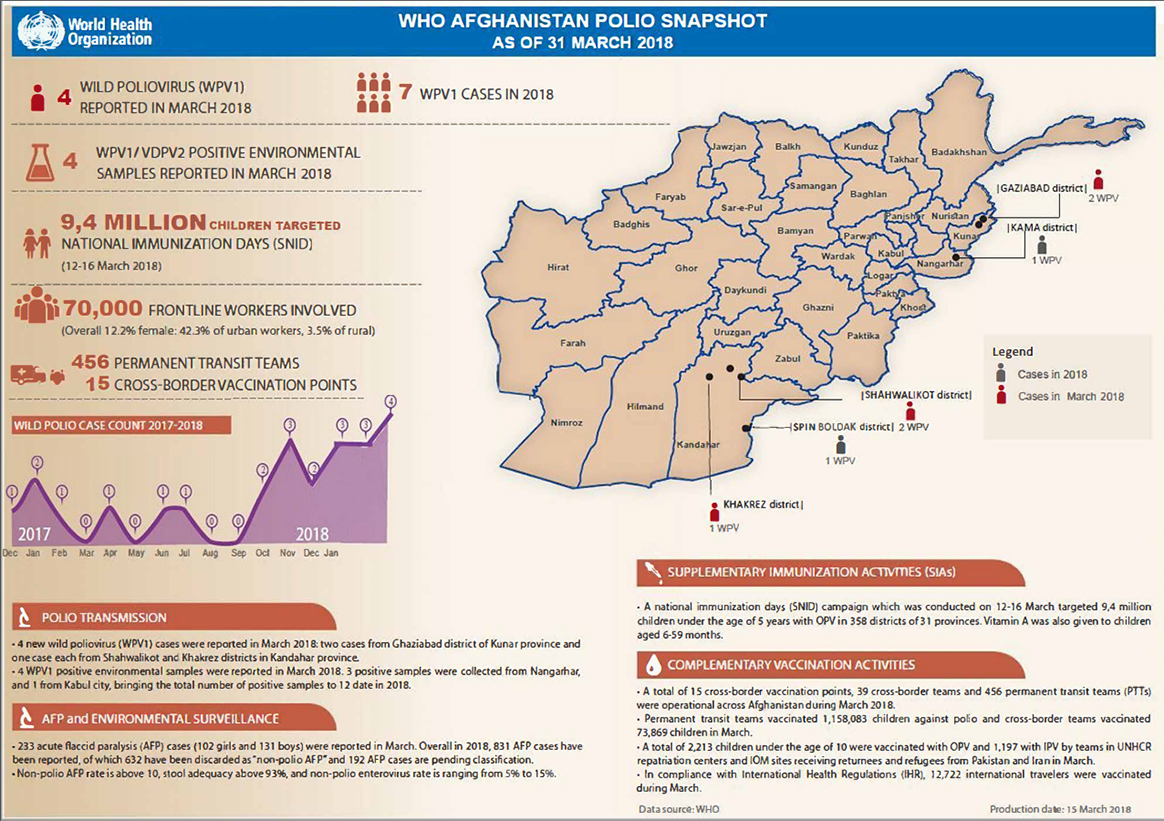

In March:

- Four cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) were reported, two cases from Ghaziabad district of Kunar province, and one case each from Shahwalikot and Khakrez districts in Kandahar province.

- 4 million children under five years of age were targeted during national immunization days in 358 districts of 31 provinces.

- Permanent transit teams successfully vaccinated 1 158 083 children against polio, whilst cross-border teams vaccinated 73 869 children.

For full update please click on pdf below.

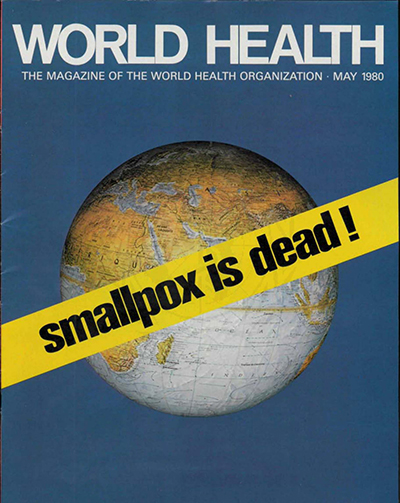

Fear of paralysis, severe illness, or death from polio and smallpox was a very real and pervasive reality for people worldwide within living memory.

In 1977, the world was close to finally being smallpox free. The number of people infected had dwindled to only one man; a young hospital cook and health worker from Merca, Somalia named Ali Maaow Malin.

Before Ali, smallpox had affected the human population for three millennia, infecting the young, the old, the rich, the poor, the weak and the resilient.

Spread by a cough or sneeze, smallpox caused deadly rashes, lesions, high fevers and painful headaches – and killed up to 30% of its victims, while leaving some of its survivors blind or disfigured.

An estimated 300 million people died from smallpox in the 20th century alone, and more than half a million died every year before the launch of the global eradication programme.

The power of a vaccine

Between 1967 and 1980, intensified global efforts to protect every child reduced cases of smallpox and increased global population immunity. Following Ali’s infection, the World Health Organization carefully monitored him and his contacts for two years, whilst maintaining high community vaccination rates to ensure that no more infection occurred.

Three years later, smallpox was officially declared the first disease to be eradicated. This was a breakthrough unlike any other – the first time humans had definitively beaten a disease.

But smallpox wasn’t the only deadly virus around

On March 26, 1953, Dr Jonas Salk announced that he had developed the first effective vaccine against polio. This news rippled quickly across the globe, leaving millions optimistic for an end to the debilitating virus.

Polio, like smallpox, was feared by communities worldwide. The virus attacks the nervous system and causes varying degrees of paralysis, and sometimes even death. Treatments were limited to painful physiotherapy or contraptions like the “iron lung,” which helped patients breathe if their lungs were affected.

Thanks to a safe, effective vaccine, children were finally able to gain protection from infection. In 1961, Albert Sabin pioneered the more easily administered oral polio vaccine, and in 1988, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative was launched, with the aim of reaching every child worldwide with polio vaccines. Today, more than 17 million people are walking, who would otherwise have been paralyzed. There remain only three countries – Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria – where the poliovirus continues to paralyze children. We are close to full eradication of the virus – in Pakistan cases have dropped from 35 000 each year to only eight in 2017.

Since there is no cure for polio, the infection can only be prevented through vaccinations. The polio vaccine, given multiple times, protects a child for life.

Better health for all

Thanks to vaccines, the broader global disease burden has dropped drastically, with an estimated 2.5 million lives saved every year from diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough), and measles. This has contributed to a reduction in child mortality by more than half since 1990. Thanks to an integrated approach to health, multiple childhood illnesses have also been prevented through the systematic administration of vitamin A drops during polio immunization activities.

Moreover, good health permeates into societies, communities, countries and beyond – some research suggesting that every dollar spent vaccinating yields an estimated US$ 44 in economic returns, by ensuring children grow up healthy and are able to reach their full potential.

Ali Maaow Malin, the last known man with smallpox, eventually made a full recovery. A lifelong advocate for vaccination, Ali went on to support polio eradication efforts – using vaccines to support better health for countless people.

Without the life changing impact of vaccines, our world would be a very different place indeed.

Efforts to protect children from polio take place all over the world, in cities, in villages, at border checkpoints, and amongst some of the most difficult-to-access communities on earth. Vaccinators make it their job to immunize every child, everywhere.

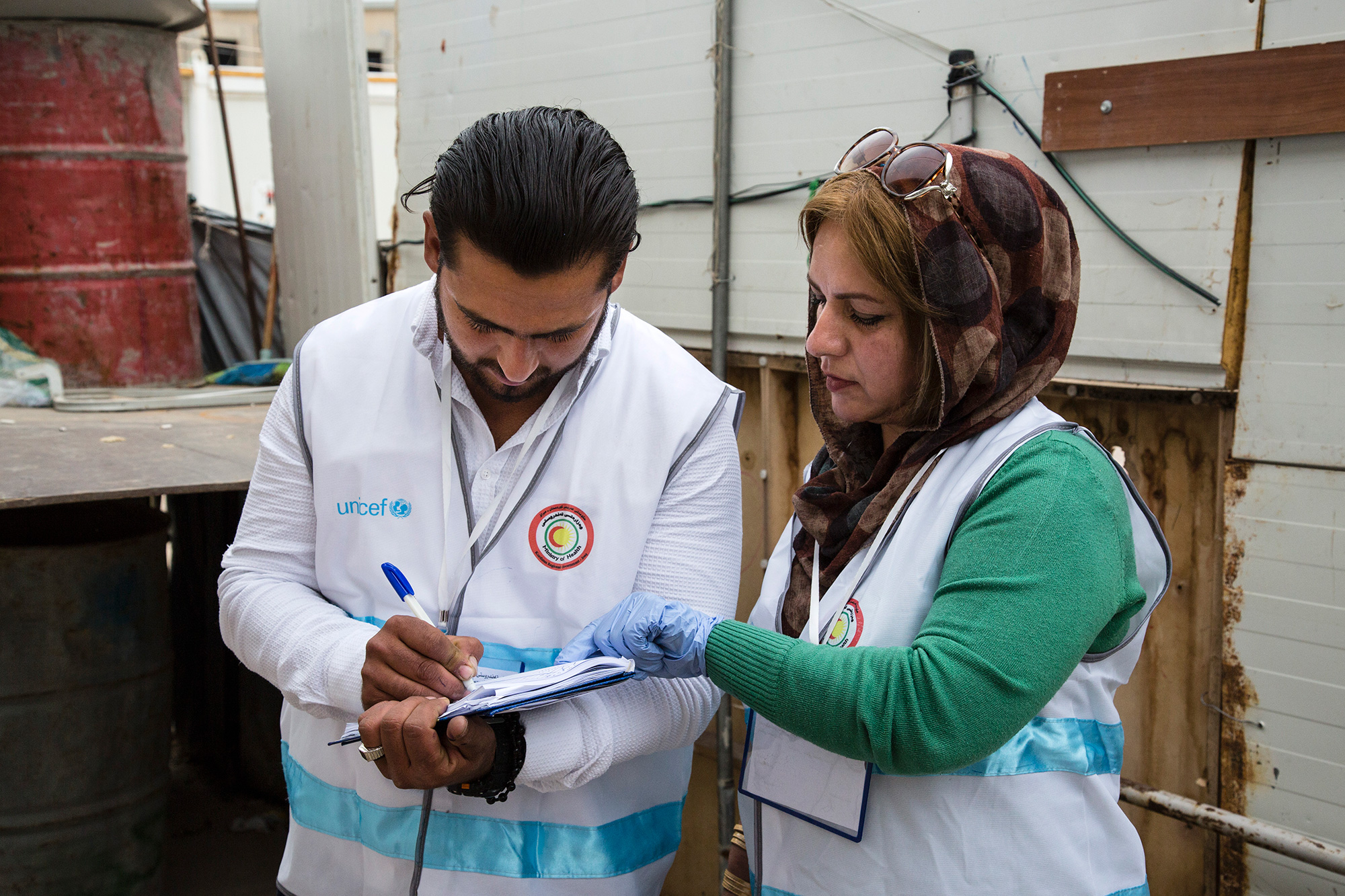

In places where families are displaced and on the move due to conflict, it is especially important to ensure high population immunity, to protect all children and to prevent virus spread. In Iraq last month, vaccinators undertook a five-day campaign in five camps for internally displaced people around Erbil, in the north of the country, as part of the first spring Subnational Polio campaign targeting 1.6 million children in the high risk areas of Iraq (mainly in internally displaced person camps, and newly accessible areas).

Binta Tijjani works to eradicate polio in her native Kano state of Nigeria. She is one of the over 360 000 frontline workers dedicated to ending polio in her country, the vast majority of whom are women. Nigeria is one of only three countries in the world yet to stop poliovirus circulation, together with Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Binta has worked in polio eradication for over 14 years. Starting as a house-to-house vaccination recorder, she was soon promoted to the role of polio campaign supervisor and now works as an independent polio campaign monitor.

“My biggest strength is my ability to work closely with our teams to ensure we reach every last child with vaccines, and advising teams so they can ask the right questions and raise important issues in each household they visit,” Binta says.

Working with the polio programme often opens up other opportunities for women to enter the workforce and utilize their skills to contribute to their communities, leading to positive investments beyond polio eradication.

“My work with the polio programme has enabled me to buy land and take care of my children’s school fees and our household needs. Currently I’ve enrolled in a course to get a certificate in catering. My dream is one day to open a restaurant,” Binta says.

Similar to Binta, Halima Waziri has been serving the polio eradication cause in different roles since 2005. Currently Halima works as a lot quality assurance sampling interpreter in Kano state, assessing the quality of vaccination coverage after immunization campaigns in her area.

“I am most proud of engaging in many productive dialogues about polio vaccination in remote and hard-to-reach areas and high-risk communities in Nigeria. This has helped me to improve my interpersonal communication skills and given me confidence in public speaking and influencing people,” Halima says.

With the money she has earned as a polio worker, Halima has opened a medicine store where she sells medicines and also acts as a community informant and focal point for disease surveillance.

Nigeria was on the brink of eradicating polio when a new wild poliovirus case was reported in 2016 after two years without any confirmed cases. Low overall routine immunization coverage is a key stumbling block to eradication, combined with ongoing violent conflict in the northeast where over 100 000 children remain inaccessible for vaccination teams.

Nigeria continues to implement an emergency response to vaccinate all children under the age of 5 to ensure they are immunized and protected, including implementing vaccination campaigns whenever security permits, vaccinating children at markets and cross-border points, and conducting active outreach to internally displaced people.

Without the critical participation of women as vaccinators, surveillance officers and social mobilizers, Nigeria would not be as close to eradicating polio as it is today. The latest nationwide immunization campaign, synchronized with countries in the Lake Chad basin, aimed to reach over 30 million children in Nigeria in April.

No wild poliovirus cases have been reported in 2017 or 2018. Binta and Halima, together with an army of frontline workers, are determined to keep it this way and secure a polio-free future for Nigeria.

From the front passenger seat of a small utility truck, Mahmoud Al-Sabr hangs out the window, looking for families and any child under five years old to be vaccinated against polio. As the car he travels in dodges rubble and remnants of buildings that once stood tall in Raqqa city, he flicks the ‘on’ switch for his megaphone.

“From today up to January 20, free and safe vaccine, all children must be vaccinated to be protected from the poliovirus that hit Syria for the second time,” he calls, beckoning families with young children who have recently returned to Raqqa city to come outside of their makeshift homes amongst destroyed buildings, to have their children vaccinated.

In 2017, amidst the protracted conflict and humanitarian crisis in Syria, an outbreak of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) was detected, threatening an already vulnerable population.

Due to ongoing conflict, Raqqa city, which was once host to half of the governorates population, had been unreached by any vaccination activity or health service since April 2016. During the first phase of the outbreak response, more than 350,000 resident, refugee and displaced children were vaccinated against polio in Syria, but “Raqqa city remained inaccessible,” says Mahmoud.

In January 2018, polio vaccinators conducted the first vaccination activity in the city since it became accessible again, following the end of armed opposition group control.

There were no longer accurate maps or microplans that vaccinators could use to guide them in their work. Unrecognizable, the city was a picture of devastation with few dwellings untouched by the violence that once caused families to flee. The house-to-house vaccination campaign that usually helps the programme to reach every child under five wouldn’t work here. Teams knew they would have to innovate to seek out families wherever they were residing to vaccinate their children.

“All children must be vaccinated to protect against poliovirus,” Mahmoud echoes around shelled out buildings, and slowly mothers and fathers carrying their children start to appear in the street.

Mahmoud and Ahmed Al-Ibraim are one of 12 mobile teams that are going street by street, building by building, by car in search of children to vaccinate. Carrying megaphones to alert families of their presence and to tell them of the precious vaccines they carry that will protect their children from the paralysing but preventable poliovirus, they slowly cover areas of the city now unrecognizable.

“No one could enter Raqqa City now for two years,” says Abdul-Latif Al-Mousa, a lawyer from the city who joined the outbreak response as a Raqqa City supervisor for polio campaigns. “So children have not been vaccinated here since that time. Now that people have returned, we are learning where they have returned from and we vaccinate them regardless.”

“We must reach each child with the vaccine to protect them – polio is preventable, why should they suffer more?” Ahmed appeals.

Campaign brings vaccines and familiar faces

Vaccines were not the only thing to return to Raqqa City in January. It was the first time that WHO polio focal point Dr Almothanna could return to Raqqa City after being force to flee under the rule of the armed opposition group. Imprisoned for refusing the demands of the group, friends and neighbours of Dr Almothanna facilitated his escape from the city in 2016.

Dissatisfied but not deterred, Dr Almothanna continued to work with the polio programme, serving the whole governorate except his own city. Over the course of the January 2018 campaign, he worked tirelessly with vaccination teams to ensure more than 20 000 children under the age of five in Raqqa City received a dose of mOPV2 to protect them against polio. For many, it was the first vaccination they had received. In the additional campaigns that followed in March 2018, even more children were reached.

The microplans developed by vaccinator teams in the first vaccination round have become a critical road map for reaching children and families with health services, accounting for the locations of returned families and information about neighbouring families that teams had not yet located. In the second round, the microplans were updated to include new families who had returned.

Syria reported 74 circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus cases between March and September 2017. It has been more than six months since the last case was reported (21 September 2017). Efforts are continuing to boost immunity in vulnerable populations, maintain sensitive surveillance for polioviruses and strengthen routine immunization to enhance the population immunity.

Forty-year-old Auta A. Kawu says the only thing predictable about working in the conflict-affected northeastern Nigerian State of Borno is its unpredictability.

“No two days in my week are alike,” he says.

As a Vaccine Security and Logistics facilitator, Auta is one of 44 specialists working with the Government, UNICEF and partners in Nigeria, who strive to ensure sufficient vaccine stock, appropriate distribution and overall accountability for vaccines in the country. Through careful management, Auta works to give every accessible child in Borno protection from vaccine-preventable diseases, including polio.

Describing a typical week in his life, he explains that if on Monday he is arranging for the vaccination of eligible children among a group of Nigerians returning back from neighbouring countries where they had fled due to fear of violence, by Tuesday he could be speaking with government personnel to find a way to safely send vaccines to security compromised areas. On Wednesday, he may find himself rushing extra vaccines to an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp, where more people have arrived than initially expected, whilst on Thursday you may find him trying to locate a cold chain technician to fix a fridge where the heat-sensitive polio vaccine must be stored.

Evidencing the energy and commitment required to work on the frontline of vaccination, Auta notes that the work never lets up. Despite an exhausting week, on a typical Friday, you might find him on the road again, travelling to a remote location where health workers have just been given access. When he gets there, he will help out once more – trying to ensure that vaccines are distributed as effectively as possible to maximize the number of children reached.

He recounts a recent story of reaching the reception area of an IDP camp in Dalori, which is located in a highly volatile area of the state. Arriving with 300 doses of oral polio vaccine, and 200 doses of measles vaccine, he was told that new arrivals were expected later that day. Many of the people coming had been under siege by non-state armed groups since 2016, and had taken the opportunity of improved security and mobility to flee to the nearest town. Very few of the young children arriving had ever been reached with vaccines.

With the screening of children eligible for measles and polio vaccines starting around 9 am, and plenty more children yet to arrive, it was quickly clear that the available doses would not be enough.

Springing into action, Auta notified the head of the security team accompanying him of the need to go to nearest health facility to bring additional doses. Once clearance was given, he rushed to Jere Local Government, a district nearby, to collect more vaccines.

In the meantime, however, there were sudden changes in the security environment. The return journey to Dalori was not cleared until late noon.

Luckily, giving up isn’t in Auta’s nature.

By the end of the day, he had successfully delivered 580 doses of oral polio vaccine and 460 doses of measles vaccines for the children in the camp, providing some of them with their first ever interaction with a health system.

The crucial role of Vaccine Security and Logistics facilitators like Auta cannot be over-emphasized. In addition to his central work, Auta also conducts advocacy visits to traditional and religious leaders and supports the planning and implementation of vaccination campaigns in inaccessible areas.

Vaccine facilitation may be unpredictable work, but Auta is secure on one thing. Thanks to the work of him, and thousands of other determined health workers, community mobilizers and with support from donors and partners including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Government of Canada, the Dangote Foundation, the European Union, Gavi – The Vaccine Alliance, the Government of Germany, the Government of Japan, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Bank and others, Nigeria is steadily on its way to being declared polio-free.

Le jour se lève dans le district sanitaire de Bol, au Tchad, et la Dre Adele commence sa journée. Elle monte dans son canoë et, après avoir jeté un coup d’œil à sa carte, commence un long voyage sur les eaux du lac Tchad. Dans quatre à six heures, se frayant un chemin parmi les roseaux, elle aura atteint une île isolée où les enfants n’ont encore jamais été vaccinés.

La Dre Adele Daleke Lisi Aluma vit dans l’une des régions du monde où la vaccination est la plus difficile. Dans le district de Bol, 45 pourcent des enfants vivent dans des îles isolées et difficiles d’accès où les obstacles géographiques, la violence, l’insécurité et la pauvreté empêchent le plus souvent de prodiguer à la population les services de santé et les autres services publics.

Son travail consiste à surmonter ces obstacles en cherchant chaque enfant non encore vacciné, tout en mettant à profit son expérience pour que le programme fasse le meilleur usage des ressources en vue d’atteindre à chaque fois le plus d’enfants possible.

Un itinéraire à planifier

La première étape de chaque campagne consiste à planifier l’itinéraire. En étudiant les cartes, en en comparant les informations, la Dre Adele et son équipe s’efforcent de trouver la façon la plus efficace d’atteindre les nombreuses îles où les vaccinateurs doivent se rendre.

« L’équipe prévoit souvent ses campagnes lors du marché hebdomadaire, car on peut alors vacciner les enfants qui accompagnent leur mère pour l’achat et la vente des produits de base », explique-t-elle.

Afin que le vaccin soit mieux accepté, la Dre Adele et ses collègues téléphonent aux anciens et aux chefs de village quelques jours avant chaque campagne afin de leur expliquer pourquoi il est si important de se protéger contre la poliomyélite et les autres maladies évitables par la vaccination.

Cette approche permet d’accroître la portée du programme. Auparavant, les vaccinateurs parcouraient parfois de longues distances, pendant de nombreux jours, avant d’arriver sur des îles où se trouvaient en réalité très peu d’enfants. Cela entraînait des gaspillages, les vaccinateurs ne parvenant pas à maintenir, sur le trajet de retour, les vaccins à une température suffisamment froide pour qu’ils puissent profiter à d’autres enfants. Aujourd’hui, une meilleure planification et l’achat de réfrigérateurs solaires pour le stockage des vaccins contribuent à résoudre le problème.

« Pour tirer le maximum d’une session de vaccination, nous devons nous assurer que nos opérations sur le terrain soient efficientes et efficaces, en manquant le moins possible d’occasions », ajoute-t-elle.

Un voyage difficile

Le lac Tchad n’est pas un plan d’eau dégagé : les voies navigables y sont entravées par des roseaux et des arbres et par la vie animale. Pour atteindre les îles, la Dre Adele utilise un canoë, naviguant adroitement dans ces eaux difficiles pendant plusieurs heures. Les équipes doivent faire preuve de la plus grande vigilance. Il leur faut avancer, maintenir les vaccins au froid et éviter les piqûres d’insectes, voire les rencontres avec les hippopotames.

Malgré ces difficultés, elle trouve son travail extrêmement gratifiant.

« À chaque fois que j’atteins un village isolé, je me sens plus motivée que jamais à poursuivre mon action. »

Opérationnelle dès son arrivée

Dès qu’elle est arrivée sur l’île, la Dre Adele commence à vacciner. La majorité des enfants qui vivent dans des villages insulaires isolés ont reçu moins de trois doses de vaccin antipoliomyélitique oral, et sont donc vulnérables face au virus. La Dre Adele s’efforce de protéger chacun d’eux.

Un membre de la famille proche de la Dre Adele a été touché par la poliomyélite et cette expérience est pour elle un véritable moteur. Auparavant, elle a participé à des campagnes de vaccination et à la surveillance épidémiologique de cette maladie en République démocratique du Congo et en Haïti, dans le cadre d’une carrière qui l’a menée partout dans le monde.

Des résultats tangibles

À chaque campagne, la Dre Adele vaccine des centaines d’enfants, mais recherche également des signes du virus.

Lors d’un récent déplacement dans les îles, elle et son équipe ont découvert un enfant atteint de paralysie flasque aiguë, un signe potentiel de poliomyélite, qui n’avait pas été signalé au réseau de surveillance de la maladie. Il s’est finalement avéré que l’enfant n’avait pas la poliomyélite, mais cet exemple montre que le programme doit absolument continuer d’intervenir dans ces zones difficiles d’accès, de vacciner les enfants et d’inciter les communautés à signaler tout cas présumé.

La Dre Adele contribue d’ores et déjà à renforcer la surveillance en formant les habitants de chaque village à reconnaître les signes d’un cas de poliomyélite potentiel.

Elle prévoit également de futurs déplacements : « Nous pensons revenir bientôt encadrer et accompagner les équipes de vaccination dans les zones insulaires. »

Ces efforts sont indispensables pour atteindre les communautés les plus isolées du lac Tchad.

Pour plus d’informations sur les femmes en première ligne de l’éradication de la poliomyélite (en anglais)

The Pakistan polio snapshot gives a monthly update on key information and activities of the polio eradication initiative in Pakistan.

In February:

- No new cases of wild poliovirus (WPV1) were detected.

- 39 million children were vaccinated against poliovirus by a team of almost 260 000 dedicated frontline workers.

- Teams at transit points and borders successfully vaccinated 1.4 million children.

In March, the Afghanistan polio eradication initiative conducted its first nation-wide immunization campaign for polio eradication in 2018. In just under a week, around 70 000 workers knocked on doors and stopped families in health centres, city streets and at border crossings to vaccinate almost ten million children. What an incredible achievement.

But what does a huge campaign like this take?

We had a look behind the scenes and followed the week in Herat, western Afghanistan. See what the campaign looked like from beginning to end through this photo essay.

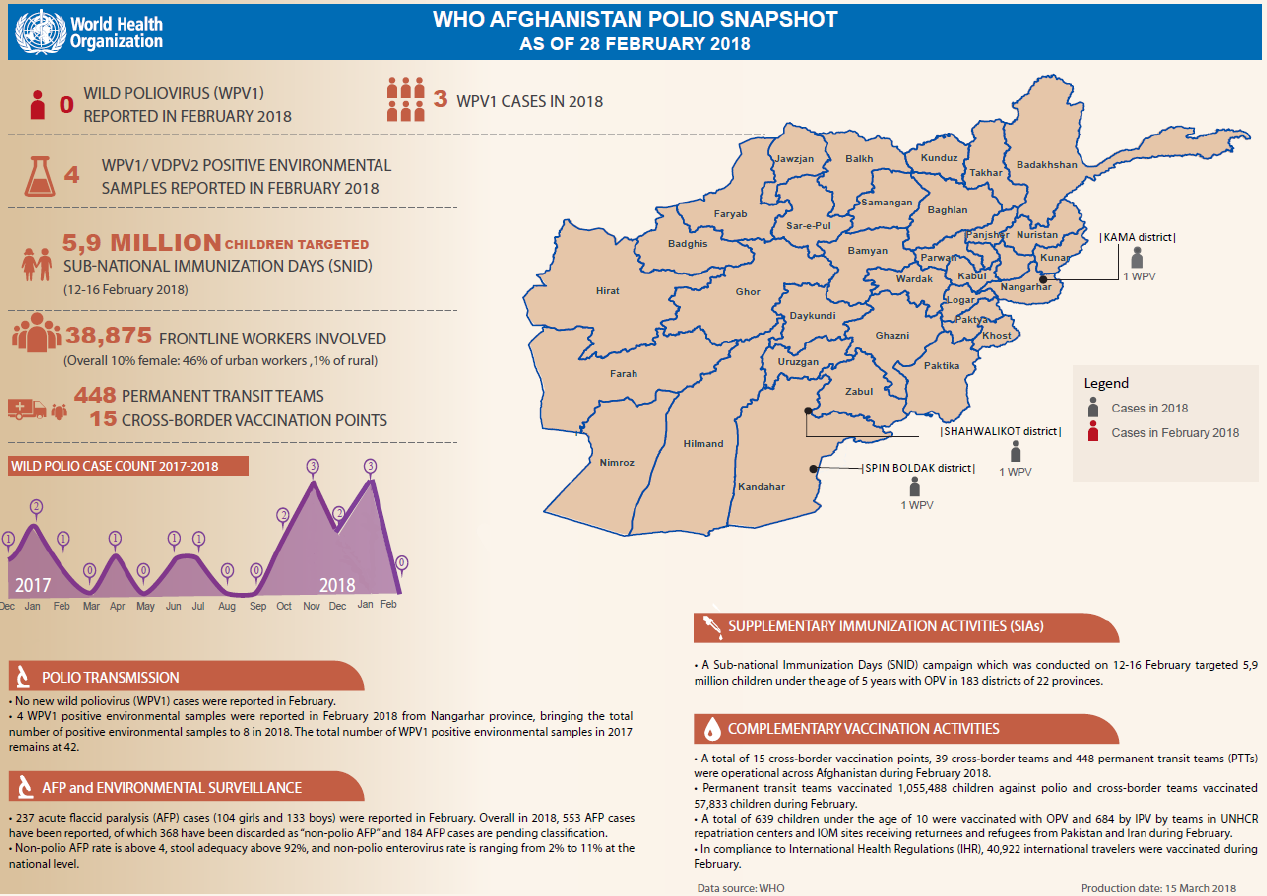

The Afghanistan polio snapshot gives a monthly update on key information and activities of the polio eradication initiative in Afghanistan.

In February:

- No new cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) were reported.

- 5.9 million children under five years of age were targeted during subnational immunization days across 22 provinces.

- Permanent transit teams successfully vaccinated 1 055 488 children against polio, whilst cross-border teams vaccinated 57 833 children.

For full update please click on pdf below.

Somalia, which stopped indigenous wild polio in 2002, is currently at risk of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2, after three viruses were confirmed in the sewage of Banadir province in January 2018. Although no children have been paralysed, WHO and other partners are supporting the local authorities to conduct investigations and risk assessments and to continue outbreak response and disease surveillance.

Underpinning these determined efforts to ensure that every child is vaccinated are local vaccinators and community leaders – nearly all of whom are women.

Bella Yusuf and Mama Ayesha are different personalities, in different stages of their lives, united by one goal – to keep every child in Somalia free from polio. Bella is 29, a mother of four, and a polio vaccinator for the last nine years, fitting her work around childcare and the usual hustle and bustle of family life. Mama Ayesha, whose real name is Asha Abdi Din, is a District Polio Officer. She is named Mama Ayesha for her maternal instincts, which have helped her to persevere and succeed in her pioneering work to improve maternal and child health, campaign for social and cultural change, and provide care for all.

Protecting all young children

Working as part of the December vaccination campaign, which aimed to protect over 700 000 children under five years of age, Bella explains her motivation to be a vaccinator. Taking a well-deserved break whilst supervisors from the Ministry of Health and the World Health Organization check the records of the children so far vaccinated, she looks around at the families waiting in line for drops of polio vaccine.

“I enjoy serving my people. And as a mother, it is my duty to help all children”, she says.

For Mama Ayesha too, the desire to protect Somalia’s young people is a driving force in her work. A real leader, she began her career helping to vaccinate children against smallpox, the last case of which was found in Somalia. Since then, she has personally taken up the fight against female genital mutilation, working to protect every girl-child.

She joined the polio programme in 1998, working to establish Somalia as wild poliovirus free, and ever since to oversee campaigns, and protect against virus re-introduction. In her words, “My office doesn’t close.”

Working in the midst of conflict

The work that Bella and Mama Ayesha carry out is especially critical because Somalia is at a high risk of polio infection. The country suffers from weak health infrastructure, as well as regular population displacement and conflict.

For Bella, that makes keeping children safe through vaccination even more meaningful.

“Through my job I can impact the well-being of my children,” she says. “For every child I vaccinate, I protect a lot more”.

Mama Ayesha echoes those words when she contemplates the difficulties of working in conflict. For most of her life, the historic district where she works, Hamar Weyne, has been affected by recurrent cycles of violence and shelling. With her grown children living abroad, she could easily move to a more peaceful life. But she chooses to stay.

“This is my home, and this is where I am needed. I am here for my team, and all the children.”

Ongoing determination

Looking up at a picture of her husband, who died many years ago, Mama Ayesha considers the determination and courage that drives her, Bella, and thousands of their fellow health workers to protect every since one of Somalia’s children. Behind her thick wooden desk, she is no less committed than when she began her career. “If I had to do it again it would be my pleasure.”

Bella has a similar professional attitude, combined with the care and technical skill that make her a talented vaccinator. Returning to her stand below a shady tree, she greets the mothers lined up with their children. As she carefully stains the finger of the first small child purple, showing that they have been vaccinated, she grins.

“I am the mother of all Somali children. I am just doing my job”.

For more stories about women on the frontlines of polio eradication

When the sun rises in the health district of Bol, in Chad, Dr Adele’s day begins. Launching her canoe into the reed-filled waters of Lake Chad, and taking a look at the map, she readies herself for the long journey ahead. In four to six hours time she will arrive at a remote island, where there are children never before reached with vaccines.

Dr Adele Daleke Lisi Aluma works in one of the most challenging areas of the world in which to vaccinate. In Bol, 45% of children live on difficult-to-access, remote islands, where geographical barriers, violence, insecurity, and poverty mean people usually do not receive health or other government services.

Her job is to overcome these barriers, seeking out every last child for vaccination, whilst using her experience to ensure that the programme makes the best use of resources to reach the most children, every time.

Planning the route

A first step for every campaign is to plan the route. Studying maps, and comparing information, Dr Adele and her team find the most efficient way to reach the multiple islands that must be visited by vaccinators.

“The team often plans campaigns to take place at the same time as the weekly market, to vaccinate children when they are with their mothers buying and selling necessities,” she says.

To increase acceptance of the vaccine, a few days before each campaign, Dr Adele and her colleagues telephone village elders and leaders, explaining why protection against polio and other vaccine-preventable diseases is so important.

This helps to improve the programme’s reach. In the past, vaccinators sometimes travelled long distances over many days to islands where there are very few children. This meant wasted vaccine, as vaccinators were not able to keep the spare vaccines cold enough on the return journey to be used for other children. Today, better planning, as well as the purchase of solar refrigerators for vaccine storage, helps to solve this issue.

“To maximise a vaccination session, we need to make sure our field operations are efficient and effective, minimizing missed opportunities” she says.

The journey

Lake Chad is made up of waterways filled with reeds, trees, and wildlife: not a flat stretch of water. To get to the islands, Dr Adele uses a paddle canoe, deftly navigating the difficult terrain for hours at a time. The teams need to be careful – while steering straight and keeping the vaccines cold, they must also watch out for insect bites – and even hippos.

Despite the challenges, she finds a huge sense of achievement in her work.

“Reaching a difficult to access village gives me every time a sense of motivation to continue.”

Arrival

Upon reaching an island, Dr Adele begins vaccination. The majority of children in remote island villages have received less than three doses of oral polio vaccine, leaving them vulnerable to the virus. One by one, Dr Adele works to protect them.

Dr Adele is driven in her work by her experience of a close family member with polio. Previously, she conducted immunization and epidemiological surveillance for polio in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in Haiti, as part of a career that has taken her all over the world.

The results

With each campaign, Dr Adele vaccinates hundreds of children, but she also looks for signs of the virus.

On a recent trip to the islands, she and her team discovered a child with acute flaccid paralysis, a potential signal of polio, who had not been reported to the polio surveillance network. While the child didn’t have polio, this underlines the crucial need for the programme to continue to access these difficult to reach places, vaccinate children, and encourage communities to report any suspected polio cases.

Dr Adele is already helping to strengthen surveillance through training community members in each village to recognise the signs of a potential polio case.

She is also planning her next journeys: “We plan to return soon to supervise and accompany vaccination teams in the island areas.”

To reach the remotest communities in Lake Chad, this is what it takes.

For more stories about women on the frontlines of polio eradication

In eastern Afghanistan, one family is helping to vaccinate every last child in their community

Zahed, his daughter Sahar, and son Mohammad all work together. But they are not working for themselves, they are working to eradicate polio.

The family lives in an indigent village in eastern Afghanistan with a diverse community. It is close to the border with Pakistan and many residents are returnees from Pakistan, families displaced by insecurity and nomads passing through. With a population that is often on the move, it is a community with high risk of poliovirus transmission – making it extremely important to vaccinate every child.

Zahed’s family are well-known. Each month, they knock on doors giving free vaccinations and educating their community about the virus.

Although sometimes they don’t have doors to knock – only tents. Known in Afghanistan as Kuchis, nomads are particularly vulnerable to polio, because they move seasonally and often miss vaccination campaigns. Historically underrepresented and often neglected, they are also isolated from health services.

Nomads at risk

Laden with water jugs, cooking equipment and clothes, the Kuchi travel with their livestock and move between provinces depending on the climate. Their goats, sheep and camels are often exchanged or sold for grain, tents and other essential items. There are an estimated two million nomads in Afghanistan.

Over 120 nomad families with 194 children under the age of five recently arrived in Zahed’s village from shelters along the Kabul River. They come in the winter because it offers warmer, more fertile ground for their animals to graze. They return to Kabul and Bamiyan during the spring, when the land is more arable.

To eradicate polio in Afghanistan, every child must be vaccinated – including the nomads. And this is exactly what Zahed’s family are doing. They go to each tent, and ensure every child is protected against polio. Last week, Zahed’s 20-year-old son Mohammad vaccinated 719 children, including nomads. “My community are happy with my service. I’m young, and it is a privilege to make a difference,’’ says Mohammad.

The family is not only protecting children, they are also contributing to community cohesion and bridging divides between nomads and residents. The challenge, however, is continuing to vaccinate nomads when they are on the move.

The motivation of Zahed’s family is impressive, but it is not always easy. A handful of people in the village reject the vaccine because they think that it is unsafe or not halal – permissible in traditional Islamic law. But watching an entire family working to eradicate polio helps break misconceptions. At the start of each vaccination campaign, Mohammad gives one of his own children the vaccine to prove that it is safe.

Becoming advocates

Zahed’s family have turned almost all the families who were refusing the polio vaccine into advocates for vaccination. Mohammad was already a prominent member of the community and was previously given a ‘Turban’ – headwear used to recognize a person who makes decisions on behalf of their community and country – to honour his relentless work to improve water, sanitation and development in his village. Now his role as a polio eradication ambassador is developing trust and increasing acceptance of the vaccine.

In 2017, three polio cases and 14 positive environmental samples were reported in eastern Afghanistan. A positive sample indicates that the polio virus is present, and that children with low immunity are at risk of contracting the disease. The first polio case of 2018 was also reported in eastern Afghanistan, making it an urgent priority location for nationwide eradication.

In the village, polio has almost been eradicated. But this is not enough for Zahed’s family. As they prepare for their next vaccination round, they are determined not to stop their work until everyone in their community – wherever they are from – is safe from polio.