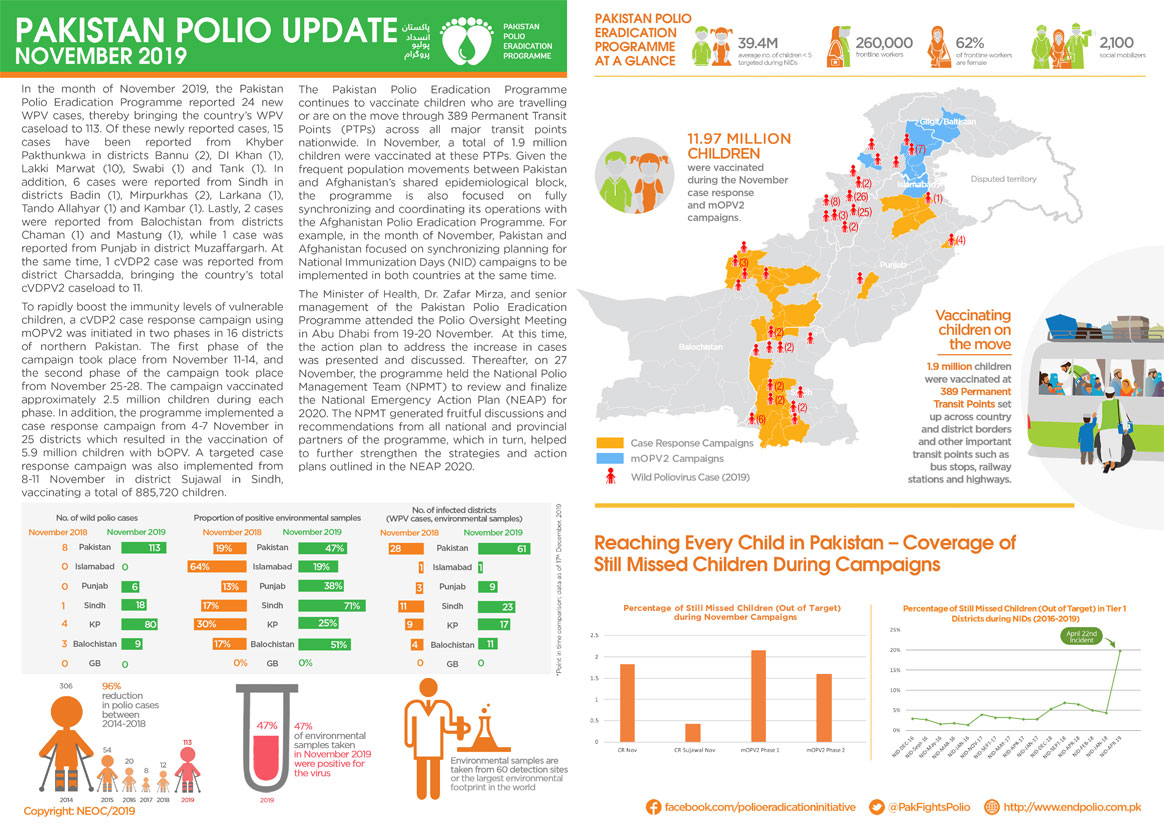

In November

- 11.97 million children were vaccinated during the November case response and mOPV2 campaigns.

- 1.9 million children were vaccinated at 389 Permanent Transit Points.

In November

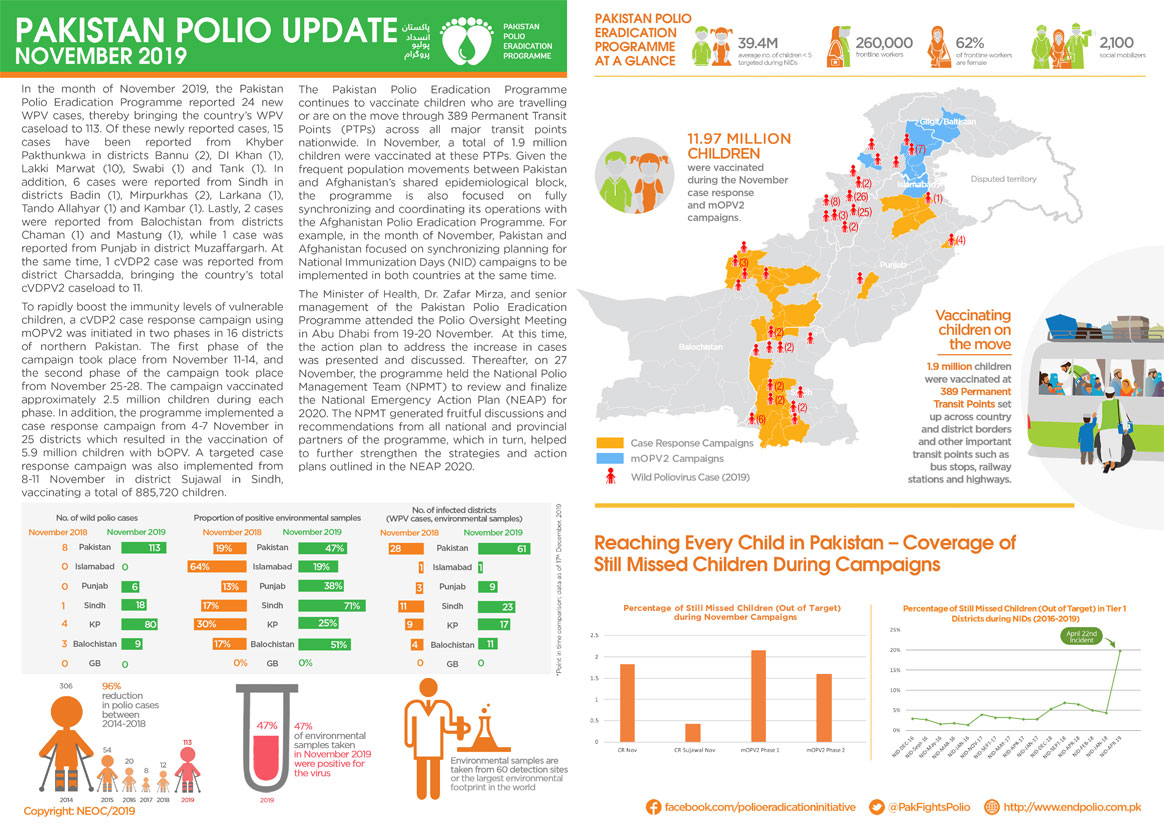

Amidst the extreme heat of the Afghan summer, Masooda, a polio outreach worker, moves with confidence between houses. Her aim is to talk to families that refuse to vaccinate their children against polio. Her energy is endless and she tops that with a smile and a warm way of talking with women and men.

Masooda has an impressive range of skills. She works as a skilled midwife with passion for her community. She is also a District Communications Officer for the polio programme, leading a team of 56 community outreach workers in her neighbourhood.

“I want to help my people – polio is a danger to every child, and we should eradicate it”, says Masooda.

Masooda recalls her early days with the programme, “I faced tough refusal families who denied their children the polio vaccine. A woman refused to vaccinate her younger sister. After one year, the sister died of measles as she hadn’t been vaccinated against it. Now, the same woman has a baby girl and she frequently takes her baby to the health centre for vaccination. Sadly, she learnt her lesson the hard way”.

Masooda leaves her house at 6:30am during immunization campaigns, just as the sun rises. She checks the outreach plans with her teams before they disperse around the town. Through the day, she makes supervisory visits to her teams and obtains updates on vaccine uptake issues. When she receives reports on absent and missing children, she converses with families in order to encourage them to vaccinate their children.

To eradicate polio from Afghanistan, Masooda thinks there is a lot more to do. She says, “I will continue to work hard, for every child to be able to walk, attend school and grow healthy. It is the whole community cause for generations to come.”

Sudan borders a number of countries facing outbreaks of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus, including Chad and the Central African Republic (CAR) to the west, and Ethiopia and Somalia to the east. Population movements between these countries increase the risk of importation of polio to Sudan. The World Health Organization and national health authorities in Sudan are scaling up efforts to reduce the risk of poliovirus transmission to the country.

To prevent a possible outbreak, health authorities have been working amidst immense operational challenges to carry out vaccination campaigns and strengthen disease surveillance. Public health teams in Sudan and CAR are collaborating to share details of vaccinated refugee children with their country of origin, and exchange information on upcoming supplementary immunization activities and reported cases of Acute Flaccid Paralysis.

Sudan was declared free of wild poliovirus in 2015, but remains at considerable risk for poliovirus importation or a VDPV outbreak. Much of the risk is shaped by Sudan’s unique population dynamics, and by the devastating effect of population movement, conflict and instability affecting routine immunization. Additionally, nomads, who account for around 10% of Sudan’s population, regularly move across borders to graze animals in Chad and CAR.

Over 8 million children under the age of five are estimated to live in Sudan – an age group considered to be most vulnerable to contracting and being paralyzed by poliovirus. Sudan also has large numbers of internally displaced people and refugees, many in the areas of the country with the lowest levels of routine immunization, such as the Darfur region.

In September and October 2019, states on the border between Sudan and CAR implemented accelerated routine immunization to provide children with coverage against a variety of vaccine-preventable diseases. Teams conducted reviews of vaccination facilities and posts in border areas, and orientation sessions were held in healthcare settings to reinforce reporting cases of Acute Flaccid Paralysis. Children received oral polio vaccine, pentavalent vaccine, and inactivated polio vaccine. Initial data from the campaigns suggests a spike in coverage, with teams reaching many children previously unprotected.

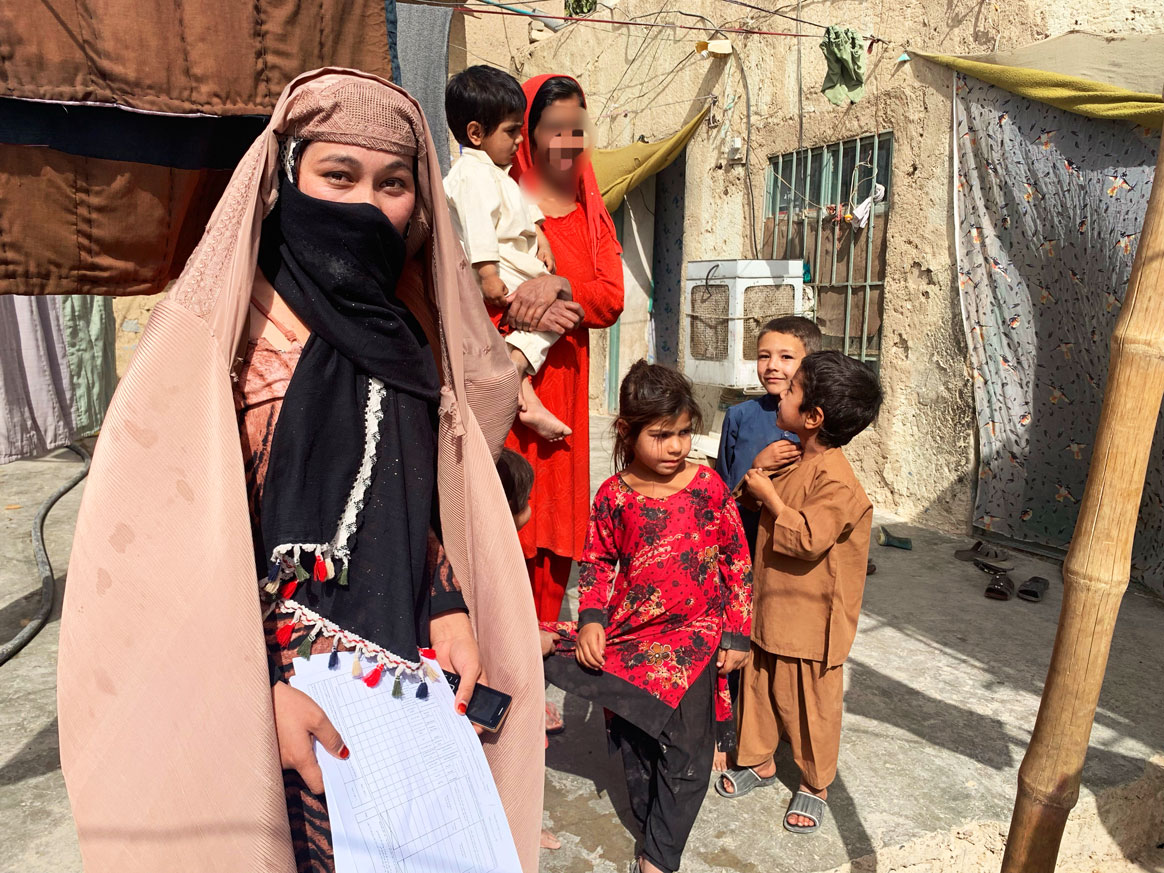

In October

In November:

Q: Outbreaks of circulating Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) are popping up in a lot of countries. How do you explain this? Did the programme know this would happen after the oral polio vaccine ‘switch’?

There have been 47 cVDPV2 outbreaks in 20 countries since the switch in April 2016. Some of these outbreaks are spreading over more than one country. Taking the three years before the switch as a frame of reference, there were 8 cVDPV2 outbreaks in five countries altogether in 2013, 2014 and 2015.

Based on epidemiological modelling studies, we anticipated cVDPV2 outbreaks following the removal of the type 2 component from oral polio vaccine in 2016, via the trivalent to bivalent OPV “switch”. And we anticipated that VDPV cases would outnumber wild poliovirus cases in the endgame. However, what the modelling did not predict was the number and scale of these outbreaks, some of which have proven very difficult to stop.

The reason we are seeing a growing number of cVDPV2 outbreaks, particularly in Africa, is the result of a growing cohort of children without mucosal immunity to type 2 poliovirus, while at the same time the [polio] programme uses monovalent oral polio vaccine type 2 (mOPV2) to respond to existing cVDPV2 outbreaks.

The monovalent vaccine [mOPV2] is currently our only tool to interrupt transmission of cVDPV2 and it is very effective when there is sufficient vaccination coverage in the communities we are targeting to avoid an outbreak. However, when campaign quality is poor and not enough children are reached with the vaccine, we run a risk of seeding new viruses among under-immunized populations. There has been evidence of this happening in and outside of outbreak response zones. We are currently developing a new strategy for stopping cVDPV2 outbreaks, and at the same time preventing new outbreaks.

Q: With a limited global stockpile of mOPV2, is there sufficient vaccine to respond to these and future outbreaks?

No. Current mOPV2 stock is insufficient to cater for the number of outbreaks and the sizes of populations requiring it. The GPEI is working with vaccine manufacturers to boost production of mOPV2 and we expect to meet targeted quantities in 2020.

The vaccine will continue to be used for cVDPV2 outbreak response until a new and more genetically stable oral polio vaccine, known as novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2), currently under clinical development, is available.

Q. What does increased production of mOPV2 mean for vaccine manufacturers in terms of containment? On one hand, the polio programme is asking for more live type 2-containing OPV. And on the other, it’s pushing for strict containment of all type 2 wild and Sabin polioviruses.

It’s a balance. The world needs enough mOPV2 stocks to help with the elimination of cVDPV2, and type 2 live attenuated poliovirus is needed to produce this vaccine. Yes, we are asking vaccine manufacturers to make more vaccine, but [vaccine] production and containment of type 2 virus are not mutually exclusive pursuits. Polio vaccine manufacture is costly, particularly when demand calls for rapid scale-up of outputs. Containment is also costly. But this is not a reason to put it on hold and stop efforts to ensure safe and secure handling and storage of virus. Quite the opposite: the impetus for putting in place adequate biorisk management systems should be greater, given the higher level of risk of human exposure to poliovirus in and around these facilities.

Q. What about manufacturers of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV)? Can they afford to relax?

IPV is made with killed, or inactivated strains of wild poliovirus types 1, 2 and 3, or their Sabin counterparts. Any facility manufacturing polio vaccines using the type 2 serotype – be it wild or Sabin ̶ and type 3 wild poliovirus since the declaration of its global eradication in October, is required to implement containment measures set out by WHO. This of course also applies to any other type of facilities holding the viruses, for example, research or diagnostic labs.

Holding on to these viruses is a risk and responsibility, and appropriate measures must be taken to protect communities from reintroduction and resurgence.

The world needs IPV and will continue to need it for the foreseeable future. We need vaccine production to continue in well-managed facilities that incorporate GAPIII approaches to biorisk management.

Q. of Sabin 2 remains a priority, while simultaneously, mOPV2 made up of Sabin 2 is being used in countries around the world. What gives?

First, we must be clear that use of mOPV2 is not a decision that is taken lightly. A thorough risk-benefit analysis is conducted before an advisory committee makes a recommendation and it is submitted to the Director-General of WHO for his approval.

It is never ideal to use mOPV2 and reintroduce Sabin 2, which should be under containment. However, as I mentioned earlier, mOPV2 is currently the only tool available to stop outbreaks of cVDPV2 and we must use it.

The reason we continue to push for containment of Sabin 2 viruses in countries not experiencing cVDPV2 outbreaks is precisely to prevent further emergences of VDPV2, which can cause outbreaks of cVDPV2 more easily now because of the very low population mucosal immunity to type 2 poliovirus.

Q. sounds like we are fighting fire with fire with mOPV2. Are we?

Many outbreaks have been stopped using mOPV2. However, in areas with low routine vaccination coverage, and thus low immunity, we are indeed reintroducing Sabin 2 in naïve populations and seeding new outbreaks. We are currently reviewing all aspects of our cVDPV2 approach and developing a new strategy that examines all options and tools ensuring we are using each for full impact. This includes improving our outbreak response so that it is appropriate in scope and effective, and accelerating the development and roll-out of a new vaccine that is less likely to seed outbreaks.

Q: When will nOPV2 be available?

Clinical trials are underway. There are numerous influencing factors but if all goes according to plan, our estimate is that approximately 100 million doses of the vaccine could be ready by mid-2020, with another 100 million by the end of the year. We are also working with the WHO prequalification team, which independently reviews all vaccine data to ensure a consistent quality in accordance with international standards to enable the vaccine to be used as quickly as possible by affected countries under an Emergency Use Listing (EUL), a risk-based procedure for assessing vaccines for use during public health emergencies—such as polio.

The vaccine is also being developed for types 1 and 3 polioviruses; however, this is further away in terms of production.

In September

“Tears were rolling down her cheeks. She was a true embodiment of pain and fatigue. She had huddled to her chest an eleven-year-old boy whose thin legs were hanging down, hampering her while she walked. I was stunned by the scene and stopped. I was curious to ask the woman what had happened to the child she was carrying. The poor woman wiped her tears to reply to me and revealed that out of her six children, three were suffering polio paralysis.”

Aziz Memon is narrating his first encounter with a child suffering from polio. The experience proved lifechanging. Over 22 years, he has risen to become one of the most influential philanthropists working to end polio in Pakistan.

22 years, 200,000 vaccine carriers, and millions raised to end polio

Aziz Memon is a good person to speak to if you want to get an insight into Rotary’s work in Pakistan. Chair of the Pakistan National PolioPlus Committee, Aziz is also a member of the International PolioPlus Committee. He has won multiple awards for his work to defeat the virus, and in October was announced as the first incoming Rotary Foundation Trustee to be appointed from Pakistan.

Aziz is most proud of his national committee’s work. He explains, “The committee has funded over 200,000 vaccine carriers for the entire EPI programme in Pakistan.”

“We have also supported vaccination at borders through permanent transit points, improved routine immunization at Permanent Immunization Centers, and helped provide basic medical care through female health workers. We have improved quality of life for families through solar filtration plants to provide clean water and have educated illiterate communities through providing speaking books. Rotarians create advocacy in schools, colleges, with Ulemas [Islamic religious scholars] and in their communities.”

With the support of Aziz and others, Rotary International has contributed millions of dollars to eradicate polio in Pakistan through the Government, WHO and UNICEF.

A chance to make history

The global drive to root out polio has some way to go still, with the poliovirus remaining in Afghanistan and Pakistan. To break the impasse an intensive, innovative and persistent effort is required.

“Rotary International’s mission to eradicate polio globally is our top priority and Rotary has taken this mission forward and helped and supported governments in other polio endemic countries to eradicate this terrible disease. It will be a privilege to be part of history when polio is eradicated, the second disease to be wiped out after smallpox,” Aziz explains.

Aziz reiterates that vaccine hesitancy and misinformation are two of the remaining challenges in the fight against polio in Pakistan.

“Misinformation spread through social media creates fear of the polio vaccine. Some security concerns still persist in tribal areas and there is weak accountability in places.”

In response, Rotary is supporting innovative strategies to address the challenges related to vaccine hesitancy. Aziz says, “Hesitancies must be skillfully addressed. We are working with Ulemas and religious scholars in all four provinces to create a positive image. Social media is playing a very strong role in averting misconceptions.”

Rotary is also a critical support to polio survivors who cannot afford their medical expenses. Aziz explains, “Rotary funds WHO to support a rehabilitation programme for polio victims. The Rotary Club of Karachi also sponsors a community project called the Artificial Limb Center which provided prosthesis, caliphers, crutches and wheelchair for polio victims and amputees as well as those injured in accidents.”

Dreaming of a polio-free Pakistan

Polio eradication in Pakistan has been a long journey but Aziz is motivated to overcome the remaining challenges.

“I motivate my fellows by nominating them for the Polio Free Service awards; publicizing their projects and activities in the monthly PolioPlus newsletter and honoring their services during the annual District Conference.”

A polio-free country is a dream for Pakistan. Reflecting on his feelings when India ended polio, to the joy of Rotarians worldwide, Aziz says, “It was good to know that a country like India could eradicate polio. It gives us hope that Pakistan can do it too, and we will soon be polio free.”

“Rotary was there at the beginning of the global effort to eradicate polio. If we stop now, polio may bounce back. We’ve done too much: we’ve made too much progress to walk away before we finish.”

The polio eradication campaign needs your help to reach every child. Thanks to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, your contribution to Rotary will be tripled. Donate now.

In October:

Abdullahi Mahamed Noor, hailing from Mogadishu in Somalia, wears multiple hats. By day, he is an experienced and dedicated polio programme zonal coordinator. By night, you can find him racing down the court as president of the Somali Basketball Federation.

Mahamed’s journey to end polio started in 1999, as a vaccinator in Adale District of Middle Shabelle in Southern Somalia. Since then, he has worked to combat multiple polio outbreaks in his country, including the current cVDPV outbreak.

Mahamed strongly believes that eradicating polio isn’t just about delivering the vaccine. To maintain high immunity levels, the programme must deliver a clear message about the safety and importance of the vaccine and help communities become better informed. To achieve this goal, Mahamed uses his sporting connections to combine basketball with innovative polio immunization messages, with the objective of increasing awareness throughout his community.

Last year, Mahamed took advantage of a Vaccination Week to deliver messages on polio eradication at several basketball games held in Mogadishu. “When people come to the stadium, they see messages on polio awareness and how important it is to vaccinate children to build their immunity against polio virus. They pass those messages to family and community members,” he explains.

From 1999 to 2010, a period during which Somalia suffered several polio outbreaks, the inaugural ceremonies of most of the major sports activities in Somalia would begin with statements encouraging people to vaccinate their children against polio.

Currently, Mahamed supports polio officers to develop comprehensive microplanning for immunization campaigns in Somalia. He emphasizes fostering trust between frontline workers and communities, since the polio workers in Somalia travel door to door to deliver vaccine. The basketball games that he organizes in his spare time help to increase acceptance of polio workers in the community.

“Part of my job is to convince the families who refuse to vaccinate their children. I quite often use my experience of being involved in basketball to educate them on benefits of polio vaccination and preventing disability related to poliovirus.”

Sportspeople are active in the fight to end polio the world over. Ade Adepitan, a British Paralympian, wheelchair basketball player and broadcaster, who is himself a polio survivor, is a strong advocate for polio eradication. In Pakistan, cricketers often promote polio eradication campaigns during the highly watched and well-attended matches.

In many parts of Somalia, poverty, conflict, internal displacement and weak health infrastructure often mean that vaccination levels remain relatively low. Amidst these trying circumstances, dedicated workers like Mahamed are playing a critical and innovative role in educating communities about polio and the absolute importance of vaccination to defeat the disease.

In August:

Compared to the busy streets of Hargeisa, Somaliland, just 20 kilometres outside of the city are broad stretches of barren land—home to the nomads. Nomadism is part of Somalia’s culture, and there are thousands of families throughout the country who lead pastoral lifestyles, raising livestock and moving their animals and families as the seasons change. Their frequent movement means that children are not always nearby a health clinic to receive their scheduled vaccinations on time. Such disruption or delay in receiving vaccines can result in low or no protection against common childhood infections.

If children are not immunized against polio, they risk contracting the virus and developing paralysis. They also risk passing polioviruses to other under-immunized children. But the polio eradication teams are committed to reach every last child with polio vaccine notwithstanding challenging terrains.

Look through the lives of polio vaccinators in Somaliland on the third day of the vaccination campaign activities as part of the larger efforts to reach over 1.1 million children with the oral polio vaccine.

As the sun sets across Sindh province, exhausted polio eradication volunteers head home after a busy vaccination campaign. Each has personally vaccinated hundreds of children. In total, it has taken just a week for 9 million children under the age of five to receive two drops of oral polio vaccine, boosting their immunity against the virus.

In the crowded office of Jan Sayyed, Ali Raza and Muhammad Bilal Wasi Jan however, work is only just beginning. They work in the Polio Eradication Data Support Centre, located in Pakistan’s biggest city Karachi. During the campaign, vaccinators fill in paperwork every time they distribute vaccine drops. They record the number of children reached with vaccines, their existing vaccination status, any vaccine refusals and whether the children are local to the area, or visiting.

Across a typical vaccination campaign, this generates data referring to over two million children, recorded on thousands of forms. It is the challenging job of Jan, Ali, and Bilal to label and classify all this data so that it can be uploaded to an online system and analyzed to improve the next campaign.

Data is the lifeblood of the polio programme

Waqar Ahmad, Technical Officer for Data at WHO Pakistan, believes that if immunization and disease surveillance represent the heart of the programme, then data is the lifeblood that helps the programme inch closer to vaccination.

Different kinds of reliable data help the programme make decisions based on evidence. For instance, data that shows a high rate of vaccine refusals in one area allows the programme to investigate the cause further and act to persuade parents of the importance of vaccination.

But creating effective systems for gathering, sorting, and analyzing high-quality data hasn’t been easy. It has required rethinking approaches, overcoming bumps in the road, and thinking beyond the usual parameters of data management.

Pakistan’s polio data journey

Data collection and record keeping in Pakistan’s polio eradication programme began in 1997. Originally, data was collected only in very specific circumstances, such as when cases of Acute Flaccid Paralysis were detected. Such limited data collection meant that broader programme activities could not be analyzed, which increased the chances that vaccination campaigns could be ineffective. Data on other aspects could ensure that logistics were right-sized, and that human resources were deployed where they were most needed.

In November 2015, the programme introduced an online database designed to provide real-time data, named the Integrated Disease Information Management System (IDIMS).

The IDIMS database is used to store pre-, intra- and post-campaign data relating to multiple areas, including vaccination, disease surveillance, human resource planning, logistics planning, and mobile data collection. Data inputted into IDIMS is directly available for viewing and analysis at the provincial, national, and regional level. It can be cross-referenced with other polio eradication databases.

Young Pakistanis like Jan, Ali and Bilal are part of the workforce that keeps the whole system online. Once they have labelled and classified the paper forms, they pass the data onto their colleagues to be digitized and analyzed.

What’s next for polio eradication data management?

Open Data Kit software

In the Data Support Centres, employees are constantly thinking about how to further improve the IDIMS system. Jan, Ali and Bilal note that digitizing the whole data collection and management process would make the system more efficient, as well as environmentally friendly.

Data collection using Open Data Kit (ODK) software offers a way to do this. The data collection process is the same as with paper forms, except information is recorded in a mobile based application. Once vaccinators are in an area with internet, the data is directly uploaded to the ODK server and the IDIMS server. The ODK system has been rolled out in some areas of Pakistan.

Gender innovations

Gender-disaggregated data represents a new area of work for the data management teams. Data included in the IDIMS database assists with gender-conscious campaign planning at the provincial level, while a separate system analyses gender-disaggregated information at the country level. Ensuring female vaccinators are recruited for campaigns is crucial, as women can often vaccinate children in places where for cultural reasons, men cannot.

Increasing user-friendly interfaces

As part of efforts to make systems user friendly, one year ago the polio programme launched online data profiles for Union Councils (UCs), the smallest administrative units in Pakistan. These profiles are available on the National Emergency Operation Centre data dashboard and allow polio programme staff to easily extract sizeable amounts of data about the local epidemiological situation within 30 seconds, as well as compare and analyze data for the past six years.

One of the most useful, innovative aspects of the UC profiles is that they collate information on children who were persistently missed during the last six campaign rounds, with information like contact details and the immunization history of the child. Such information assists the programme in follow-up engagement with the child’s parent or caregiver to encourage vaccination.

This requires speedy information sorting and uploading. Jan notes that his team is filing information more efficiently than they used to. This helps to ensure that details are up to date for nearly every town and village.

Over the coming months and years, further innovations will be introduced to improve data efficiency, range and quality.

Campaign by campaign, form by form, data handlers like Jan, Ali, and Bilal are helping to end polio.

In July

In Union Council Kechi Baig, Quetta district, Balochistan province of Pakistan, Asma needs no introduction. When she talks, people listen. First, when she was one of the few female religious scholars at her local madrassa (school), and of late, as a champion for the polio programme.

For Asma, the segue into community health sensitization was quite natural. Her religious vocation as a teacher, also known as an Alima, and her life-long aspiration to help her community, came full circle when she became a religious support person (RSP) for the polio programme.

“I always wanted to become a doctor… but (it just so happened) I joined a madrassa and became an Alima…when I heard that the polio programme is looking for female RSPs, I took the opportunity. Even though I did not become a doctor, I can workwith doctors to serve humanity,” said Asma about her motivations.

As one of three female RSPs out of a team of 118, she has given unique credence to the polio efforts in her community. Kechi Baig accounts for a significant number of refusals to vaccinate. Community health workers are sometimes unable to make headway with refusal families. In such cases, Asma plays an important role as a faith-based counsellor, drawing upon her knowledge and expertise on religious teachings with communication skills and personal friendships within the community. Asma convinces 15-20 ‘hard refusal’ families in each vaccination campaign.

“I visit the households and leave with grandmothers convinced. As a madrassa teacher, I have seen that most females are unaware of religious teachings of Islam and the role of women to improve society. The polio fatwa (Islamic rulings) book proves to be very helpful because it contains authentic fatwas from venerated religious scholars.”

Re-appropriating polio through a religious lens

Asma realizes that bringing an attitudinal change through one-off encounters with refusal households is not enough. She saw the need for a long-term counselling relationship. Now, the polio programme team also conducts community engagement sessions with a cross-section of women across the community — from mothers to grandmothers to young students to women training at Asma’s madrassa—to raise awareness about polio.

“It is a great achievement being part of the training sessions about polio and health where I get to talk about the fatwa book. In almost every campaign I work with community health workers and convince 15 to 20 hard refusals for vaccination. It’s a big opportunity to save children from polio,” explained Asma.

Religious support persons, particularly women RSPs like Asma, play a very important role in mediating how people consider their choices for and against polio vaccination through the religious interface. By incorporating educative, spiritual, and medical knowledge, faith-based counselling goes a long way in neutralizing any refusal predispositions within the community.

In June:

In May

A legion of supporters across neighbourhoods, schools, and households are creating a groundswell of support for one of the most successful and cost-effective health interventions in history: vaccination. These are everyday heroes in Pakistan’s fight against polio.

These thousands of brave individuals are championing polio vaccine within their communities to enlist the majority in the pursuit of protecting the minority — reaching the last 5% of missed children in Pakistan.

One of the major factors that determines whether a child will receive vaccinations is the primary caregiver’s receptiveness to immunization. The decision to vaccinate is a complex interplay of various socio-cultural, religious, and political factors. By educating caregivers and answering their questions, these Vaccine Heroes serve as powerful advocates for vaccination, even creating demand where previously there might have been hesitation. This is where everyday people step in to vouch for vaccination as a basic health right.

Here are some nuanced, powerful, and thought-provoking testimonies on their unwavering belief in reaching every last child:

In April

The sun often beats down on the humid forest corridors of Papua and West Papua—the easternmost provinces of Indonesia, thick with jungles and winding rivers with populations spread wide and far under these green canopies. Coupled with sketchy phone signals and the fact that electricity has yet to reach most parts of the two neighbouring provinces, a perfect storm was brewing, as poliovirus could sneakily circulate in ripe conditions.

On 8 February 2019, after extensive field investigations, Indonesia reported circulation of vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1 (cVDPV1) in Yahukimo District, Papua Province. A polio outbreak was officially declared.

Driven by the guiding ethos of reaching every last child, local public health authorities supported by the Global Polio Eradication Initiative have developed outbreak zone service delivery strategies to reach as many children as possible including at schools, at outreach and local health centres, door-to-door campaigns, or at churches and mosques.

Here are some inspiring testimonials and stories of the collective efforts to end the cVDPV in Indonesia:

Fasting? No problem

Mirnawati and Imelda are two ambitious immunization staff members at the Moswaren health centre in the South Sorong District of West Papua province. Once the mass immunization campaigns began in their district on 29 April, Mirnawati and Imelda headed to their local community school to vaccinate all children from ages 5-15 years.

Upon contacting the school administration, they realized that the school session would be out for a week-long break, right up to the beginning of the month of Ramadan—a period of fasting for the Muslim population in the community.

Thinking quickly and willing to accommodate the Muslim students, both the immunization officers quickly coordinated with the school principal to offer vaccination on the National Education Day ceremony on 2 May. Mirnawati and Imelda also went above and beyond by offering to stay past sun-down to vaccinate all Muslim students after they opened their fasts.

Adrian, 7 years old

“Hello, my name is Adrian Suu. I am 7 years old, and I am from Cenderawasih village in Yahukimo, Papua Province. I study in the first grade at the Lentera Harapan School, and I want to be a pilot when I grow up. I’m glad that I got vaccinated so I can be healthy and fly in a plane!”

The resurgence of poliovirus in Indonesia underscores the threat posed by low-level virus transmission and the need to maintain high routine immunization everywhere in the world to minimize the risk of circulation of the virus.

The first polio outbreak response rounds were conducted in March and April 2019, targeting around 1 million children each in Papua and West Papua provinces. While the immunization coverage has been high across West Papua and low-land districts of Papua, vaccine coverage has often been impeded in high-land districts, including the outbreak source—Yahukimo district – owing to mobile populations, dense forests and poor health infrastructure.

Amidst a poliovirus outbreak in Papua New Guinea, legions of women health workers and leaders are playing a critical role in ensuring children are fully protected from lifelong paralysis. In the current emergency outbreak response, women have emerged as a strong, reliable, and a decisive group that continue to administer key services in the outbreak response implementation. From medical doctors to surveillance officers to community mobilizers to health workers, women are active and present on all fronts.

World Immunization Week—celebrated in the last week of April— aims to encourage the use of vaccines as one of the safest methods to protect against diseases, including poliovirus. This year’s theme – Protected Together: Vaccines Work! – highlights “heroes” who are ensuring that people of all ages, all across the world are protected through vaccines. Women on the frontlines of the outbreak response in Papua New Guinea are a fitting example who continue to inspire the public health community across the world.

Here is a roundup of some of the extraordinary vaccine “heroes”:

Dr Fiona Kupe

Dr Fiona Kupe is a Paediatric Medical Officer at the Gerehu General Hospital in the National Capital District, Papua New Guinea. She is, in effect, a one (wo)man army as she dons multiple hats in the polio eradication efforts in her home country by searching for children with acute-flaccid paralysis (AFP) at Port Moresby General Hospital and Gerehu General Hospital. She also leads the mapping of communities – or microplanning – for all Supplementary Immunization Activities (SIAs) across three districts.

Along with that, she finds time to train vaccinators and community volunteers, all the while carrying out her clinical duties as a child specialist.

“As a paediatric doctor and a mother…every day, I keep (my) passion alive to overcome challenges and basically to do everything I can to check on children’s vaccination status whenever they come to see me for check-up. As a mother, I know that vaccines save lives. I want my child to survive with good health and I would definitely want the same for all the mothers and children I see.”

Melanie Serei

Seen most days with her trusty pet dog by her side, Melanie works in one of the most challenging areas for immunization activities as a health worker in a remote village of Terapo in Kerema, Gulf province. Geographical inaccessibility aside, Melanie constantly juggles issues of insecurity, violence and community vaccine hesitancy. But, she tries every single day to overcome barriers in her mission to reach every last child with the life-saving polio vaccination.

Building community trust and demand for vaccination were considered key tenets in the risk communication for the polio outbreak response. Melanie successfully carried out door-to-door checks on all the children in the village. Thanks to her diligence, she was quickly able to notice polio symptoms in a child that allowed adequate and rapid actions.

Dr Winnie Sadua

Working as a paediatrician in Angau Memorial General Hospital in Morobe province, Dr Winnie treats one very special patient: six-year-old Gafo—the first reported case of polio in PNG in over 18 years, triggering a national outbreak emergency.

Since his diagnosis, Gafo has gone on to become somewhat of a celebrity, a symbol of hope, and a staunch advocate for polio eradication. Through timely treatment and physiotherapy by Dr Winnie, Gafo can now walk with his signature gait. He is now healthy and excited to start school next year.

With all the patients that come to her, Dr Winnie makes sure to remind all the parents to take heed from Gafo’s case and get their children vaccinated.

In March:

On both sides of the historical 2640-kilometre-long border between Pakistan and Afghanistan, communities maintain close familial ties with each other. The constant year-round cross border movement makes for easy wild poliovirus transmission in the common epidemiological block.

As a new tactic in their joint efforts to defeat poliovirus circulation, Afghanistan and Pakistan have introduced all-age polio vaccination for travellers crossing the international borders in efforts to increase general population immunity against polio and to help stop the cross-border transmission of poliovirus. The official inauguration of the all-age vaccination effort took place on 25 March 2019 at the border crossings in Friendship Gate (Chaman-Spin Boldak) in the south, and in Torkham in the north.

Although polio mainly affects children under the age of five, it can also paralyze older children and adults, especially in settings where most people are not well-immunized. Adults may play a role in poliovirus transmission, so ensuring that they have sufficient immunity is critical to simultaneously eliminating poliovirus from the highest risk areas on both sides of the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

This is particularly important at the two main border crossing points – Friendship Gate and Torkham – given the extensive amount of daily movement. It is estimated that the Friendship Gate border alone receives a daily foot traffic of 30 000. Travellers include women and men of all ages, from children to the elderly.

Pakistan and Afghanistan first increased the age for polio vaccination at the border in January 2016, from children under five years to those up to 10 years old. The decision was in line with the recommendations of the Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations (IHR) which declared the global spread of polio a “public health emergency of international concern”,

The all-age vaccination against polio at the border crossings serves a practical implementation of another recommendation of the IHR Committee: that Pakistan and Afghanistan should “further intensify crossborder efforts by significantly improving coordination at the national, regional and local levels to substantially increase vaccination coverage of travelers crossing the border and of high risk crossborder populations.”

As part of the newly introduced all-age vaccination, all people above 10 years of age who are given OPV at the border are issued a special card as proof of vaccination. The card remains valid for one year and exempts regular crossers from receiving the vaccination again. Children under 10 years of age will be vaccinated each time they cross the border.

Before all-age vaccination began at Friendship Gate and Torkham, public officials held extensive communication outreach both sides of the border to publicize the expansion of vaccination activities from children under 10 to all ages. Radio messages were played in regional languages, and community engagement sessions sensitized people who regularly travel across the border. Banners and posters were displayed at prominent locations.

Deputy Commissioner for Khyber District in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Mr Mehmood Aslam Wazir, inaugurated the launch of All-Age Vaccination by vaccinating elderly persons at the Torkham border crossing. “Vaccination builds immunity and it is necessary for children to be vaccinated in every anti-polio campaign. The polio virus is in circulation and could be a threat to any child. The elders in our community could be carrier of the virus and take along the virus from one place to another, therefore, vaccination of every traveller, of all ages and genders, crossing Pakistan-Afghanistan border will be the key determinant to interrupt polio virus transmission in the region, and the world.”

The introduction of the all-age vaccination at border crossings is the latest example of cross-border cooperation between Pakistan and Afghanistan. The two countries continue to work closely together to ensure synchronization of strategies, tools and activities on both sides of the border.