Spera clinic clings to a shaly mountainside in Khost province, in Afghanistan’s remote Southeast. In the shade of a walnut tree in the clinic’s leafy courtyard, Rezia clears her throat, and holds up a booklet of flip cards. Fifty women sit cross-legged at her feet, listening. The silence is broken only by children murmuring, and birds chirruping in the Spring morning.

Every day, Rezia delivers education sessions on a meticulous rota of topics relevant to the needs of the local women – nutrition, breastfeeding, general health and hygiene, and vaccination. This morning’s session is on the vaccine-preventable diseases that plague remote parts of the country – polio, measles and tetanus. Her rapt audience has walked miles to the clinic, some for two hours or more, carrying the smallest of their children. When Rezia pauses for breath, they waste no time in asking questions.

50 kilometres northeast, the town of Maidan sits in a lush valley where green ears of wheat bob in every spare patch of ground, a stone’s throw from the Pakistan border. In the district clinic, Spozmai is recording the day’s health education sessions in her register. Just today, she spoke to over a hundred women of all ages from the local community.

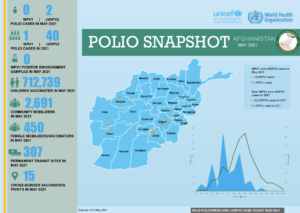

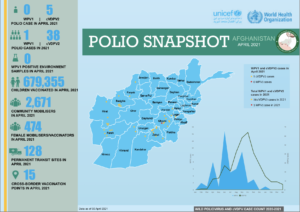

Rezia and Spozmai are part of the female mobilizer vaccinator (FMV) network – 656 women across Afghanistan whose daily work is to vaccinate children against polio and run health education sessions for women from the local community. In Khost, one FMV has been permanently assigned to every clinic for the last year. Each one is a member of the community she serves. Because of this, she has their ear. This is the FMVs’ superpower.

Maidan and Spera are in the so-called former “white areas”: parts of Afghanistan that, before August 2021, were inaccessible to outsiders, including other Afghans. The communities here are tight knit, self-sustaining and culturally conservative. After decades in isolation, trust is slow to build. This also extends to health care: turning these communities on to vaccination is painstaking work that is best done by an insider.

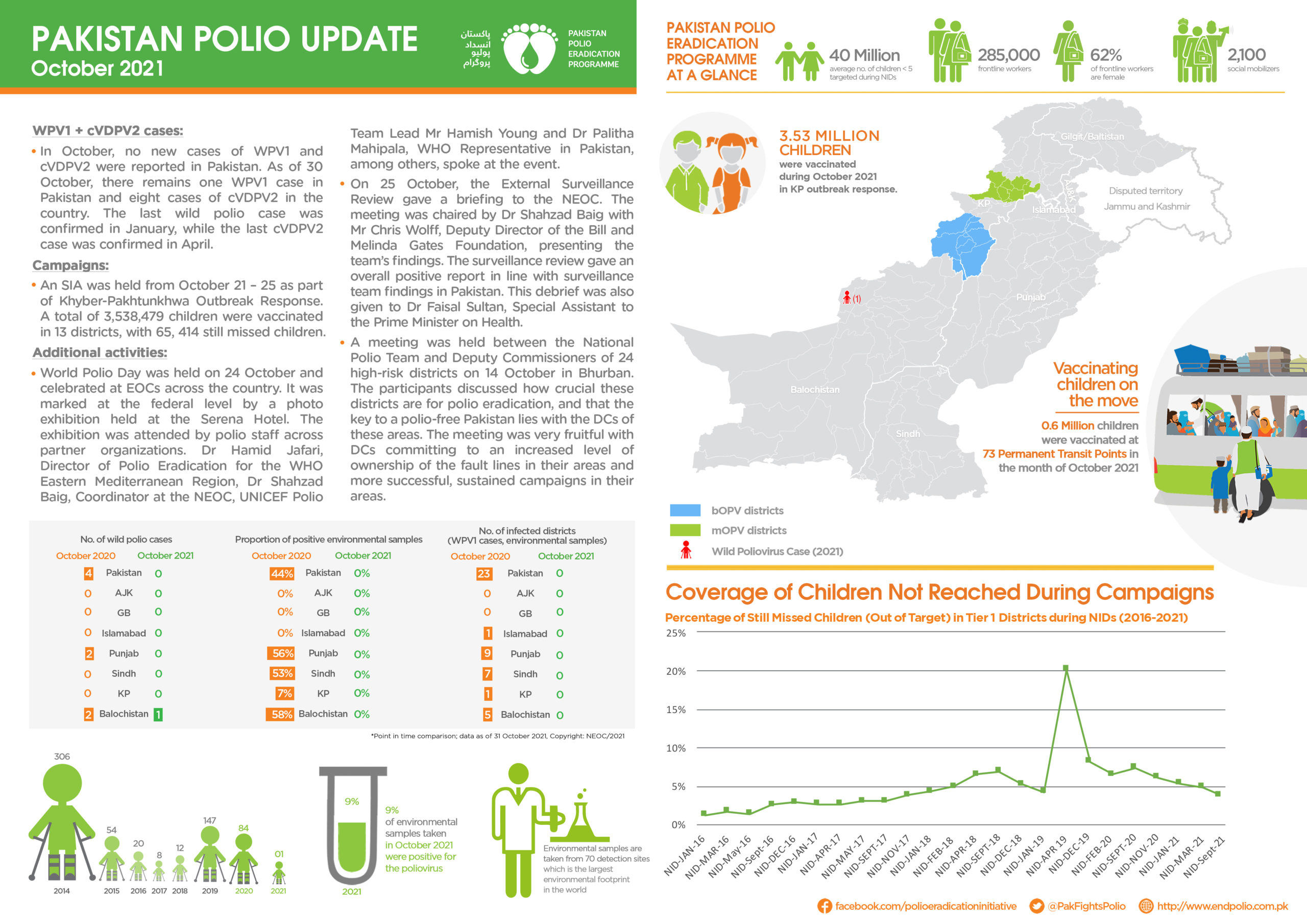

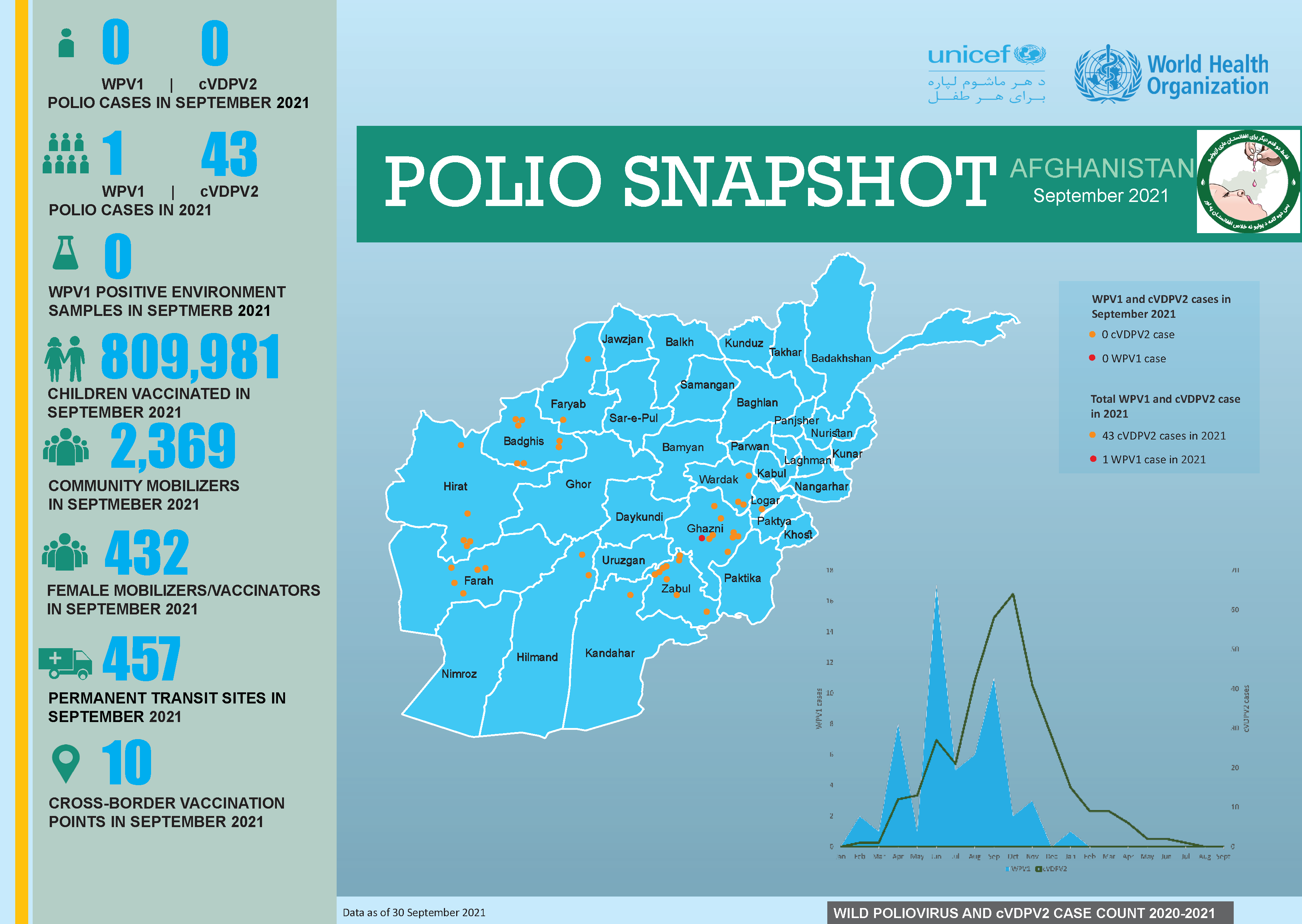

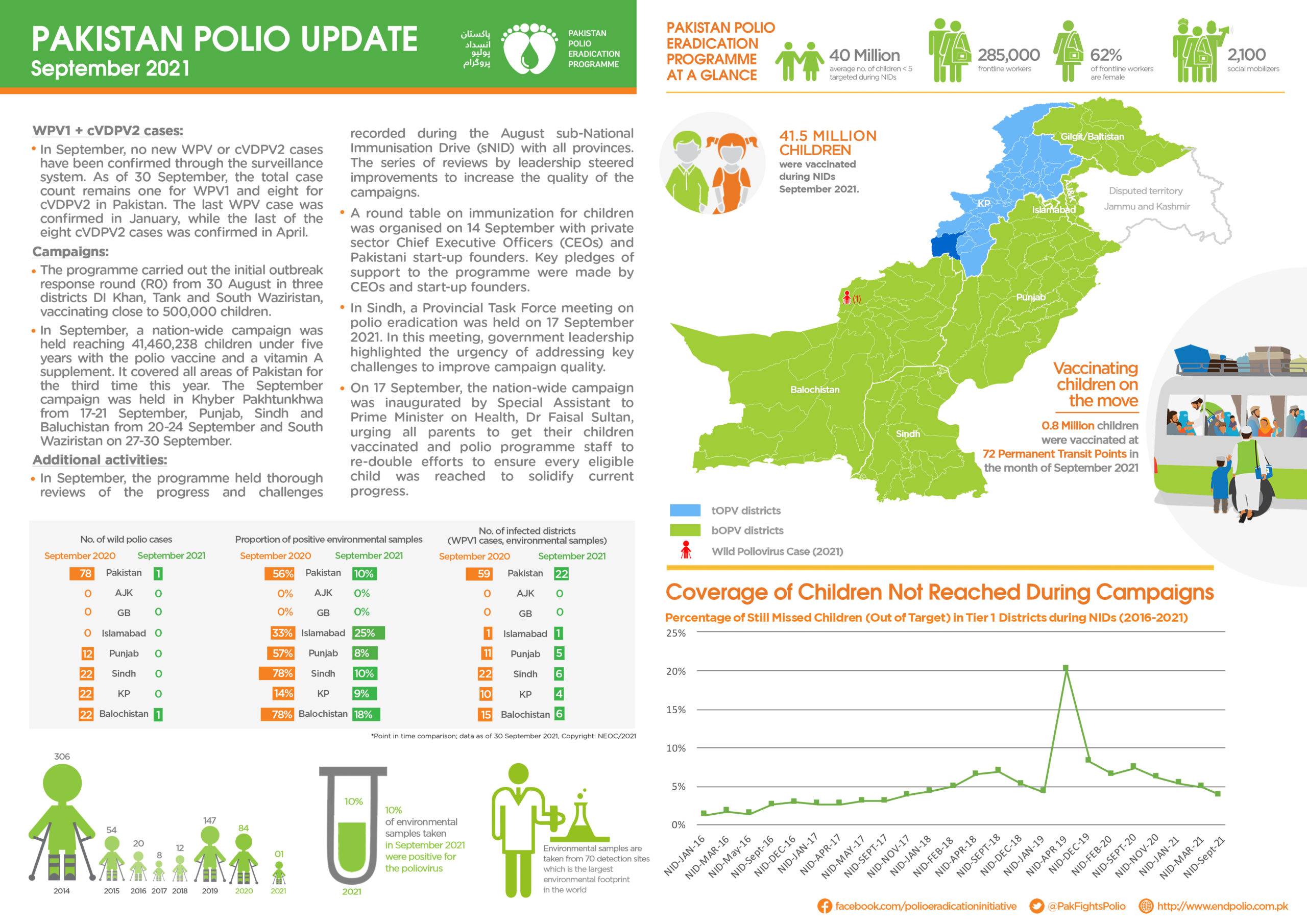

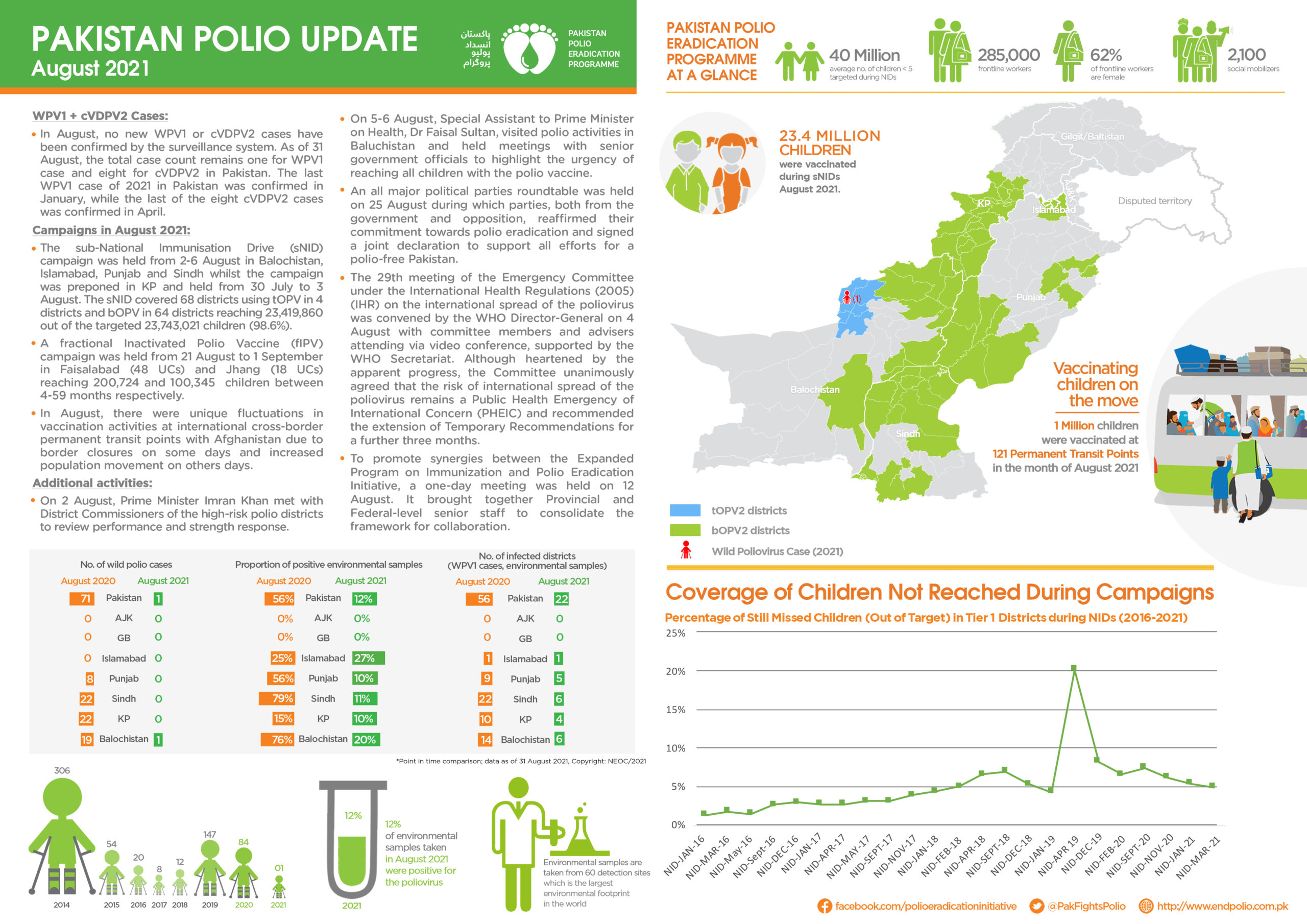

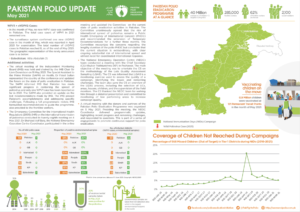

As well as being one of the last two polio-endemic countries, Afghanistan is among the top twenty countries for ‘zero dose’ children globally. The Southeast has the highest number of children missed in the regular polio vaccination campaigns, especially in Khost and neighbouring Paktika. Paktika also has one of the lowest rates of routine immunization countrywide.[1]

It’s a universal human truth that we are less likely to listen to outside voices than we are to trusted members of our own communities. This is especially true for those who live in historically isolated areas. This includes attitudes toward vaccination – for measles and tetanus, but most of all for polio.

Changing people’s minds is the first, and biggest step toward reversing this trend, and women are critical players. “I’m respected in the community,” says Rezia. “I’m a mother, a grandmother – women listen to me. I can persuade the older women, and they want their daughters to have services they didn’t have. It trickles down.”

Afghan community structures are the framework along which information moves, how support is given, and how pressure is gently applied. To change attitudes and behaviours, you need to know how these structures fit together, and where to push. Rezia and Spozmai know who needs to be persuaded first to pass the message forward. Pass information to the right people and, like a drop of ink in water, it spreads.

According to the FMVs, the level of awareness among local women is a critical factor in bridging the immunization gap. Not just knowing when and why to vaccinate their children, but having their questions answered straightforwardly, and by a trusted neighbour, has contributed significantly to changing attitudes toward vaccination. Before the FMV programme began, health information was given by midwives or doctors, but this didn’t always work, especially if the doctor was a man. Rezia smiles: “Men can’t talk to us about things like this. And women wouldn’t listen if they tried.”

As the FMVs know well, change is coming slowly. As Spozmai says, “you can’t bring changes overnight.” Evidence of the impact of the FMVs’ work on vaccine acceptance in these insular parts of the country is to date mostly anecdotal, but copious, nonetheless. Certainly, the directors of clinics and hospitals in the polio high-risk regions of the South, East and Southeast attest to tangible changes in health seeking behaviours among their patient catchment populations since the programme began – especially among women.

When it comes to ending the grip polio and other vaccine-preventable diseases hold over Afghan communities and closing the gap on zero dose children, the FMVs’ role is critical. In health facilities in every corner of the country, these women are the mortar that is slowly filling the gap.

By Kate Pond, UNICEF Afghanistan

[1] From the forthcoming Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Polio in Afghanistan, UNICEF Afghanistan (December 2023).