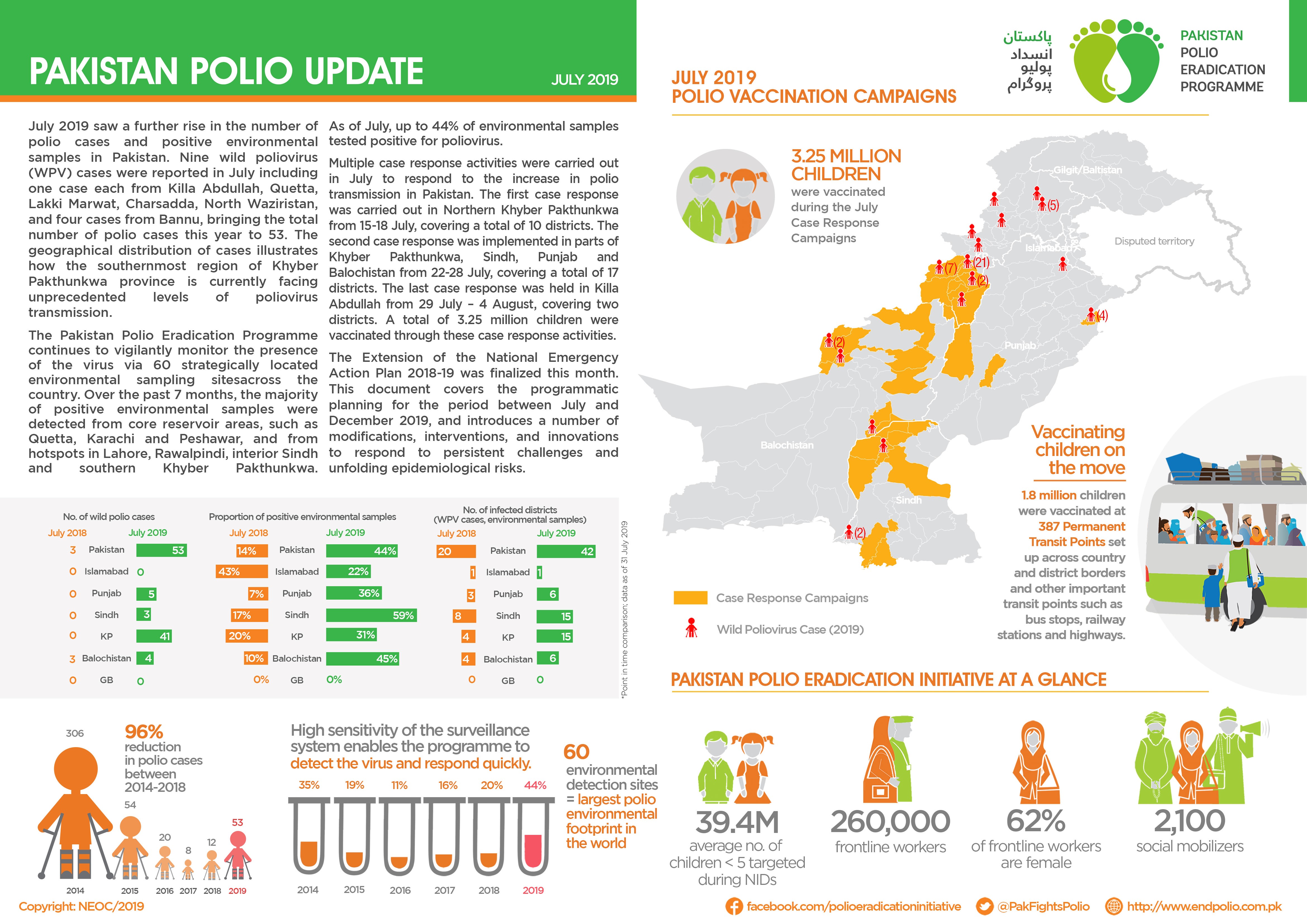

In July

- The Extension of the National Emergency Action Plan 2018-2019 was finalized in July.

- 3.25 million children were vaccinated during the July Case Response Campaigns.

- 1.8 million children were vaccinated at 387 Permanent Transit Points.

In July

In Union Council Kechi Baig, Quetta district, Balochistan province of Pakistan, Asma needs no introduction. When she talks, people listen. First, when she was one of the few female religious scholars at her local madrassa (school), and of late, as a champion for the polio programme.

For Asma, the segue into community health sensitization was quite natural. Her religious vocation as a teacher, also known as an Alima, and her life-long aspiration to help her community, came full circle when she became a religious support person (RSP) for the polio programme.

“I always wanted to become a doctor… but (it just so happened) I joined a madrassa and became an Alima…when I heard that the polio programme is looking for female RSPs, I took the opportunity. Even though I did not become a doctor, I can workwith doctors to serve humanity,” said Asma about her motivations.

As one of three female RSPs out of a team of 118, she has given unique credence to the polio efforts in her community. Kechi Baig accounts for a significant number of refusals to vaccinate. Community health workers are sometimes unable to make headway with refusal families. In such cases, Asma plays an important role as a faith-based counsellor, drawing upon her knowledge and expertise on religious teachings with communication skills and personal friendships within the community. Asma convinces 15-20 ‘hard refusal’ families in each vaccination campaign.

“I visit the households and leave with grandmothers convinced. As a madrassa teacher, I have seen that most females are unaware of religious teachings of Islam and the role of women to improve society. The polio fatwa (Islamic rulings) book proves to be very helpful because it contains authentic fatwas from venerated religious scholars.”

Re-appropriating polio through a religious lens

Asma realizes that bringing an attitudinal change through one-off encounters with refusal households is not enough. She saw the need for a long-term counselling relationship. Now, the polio programme team also conducts community engagement sessions with a cross-section of women across the community — from mothers to grandmothers to young students to women training at Asma’s madrassa—to raise awareness about polio.

“It is a great achievement being part of the training sessions about polio and health where I get to talk about the fatwa book. In almost every campaign I work with community health workers and convince 15 to 20 hard refusals for vaccination. It’s a big opportunity to save children from polio,” explained Asma.

Religious support persons, particularly women RSPs like Asma, play a very important role in mediating how people consider their choices for and against polio vaccination through the religious interface. By incorporating educative, spiritual, and medical knowledge, faith-based counselling goes a long way in neutralizing any refusal predispositions within the community.

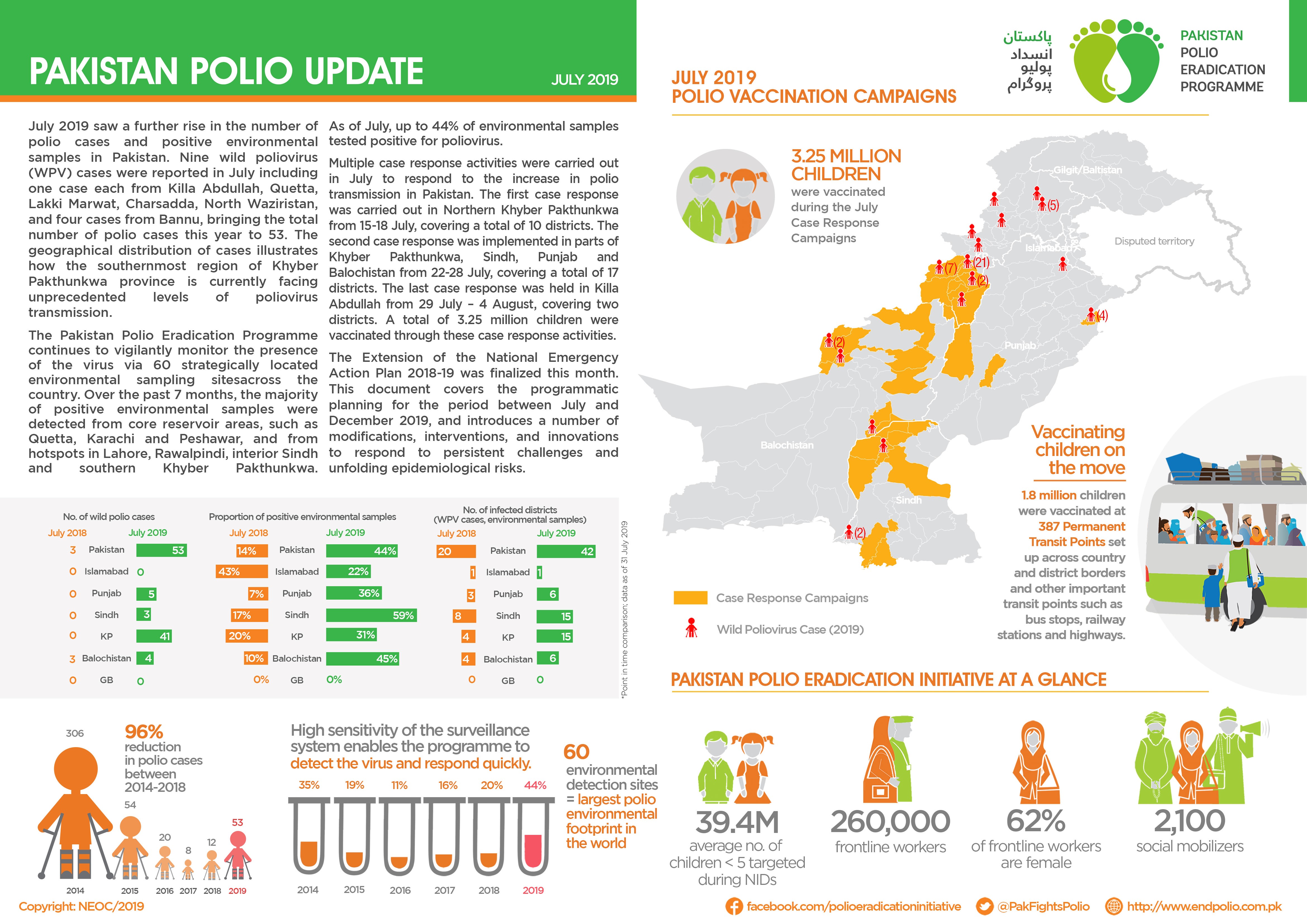

In June:

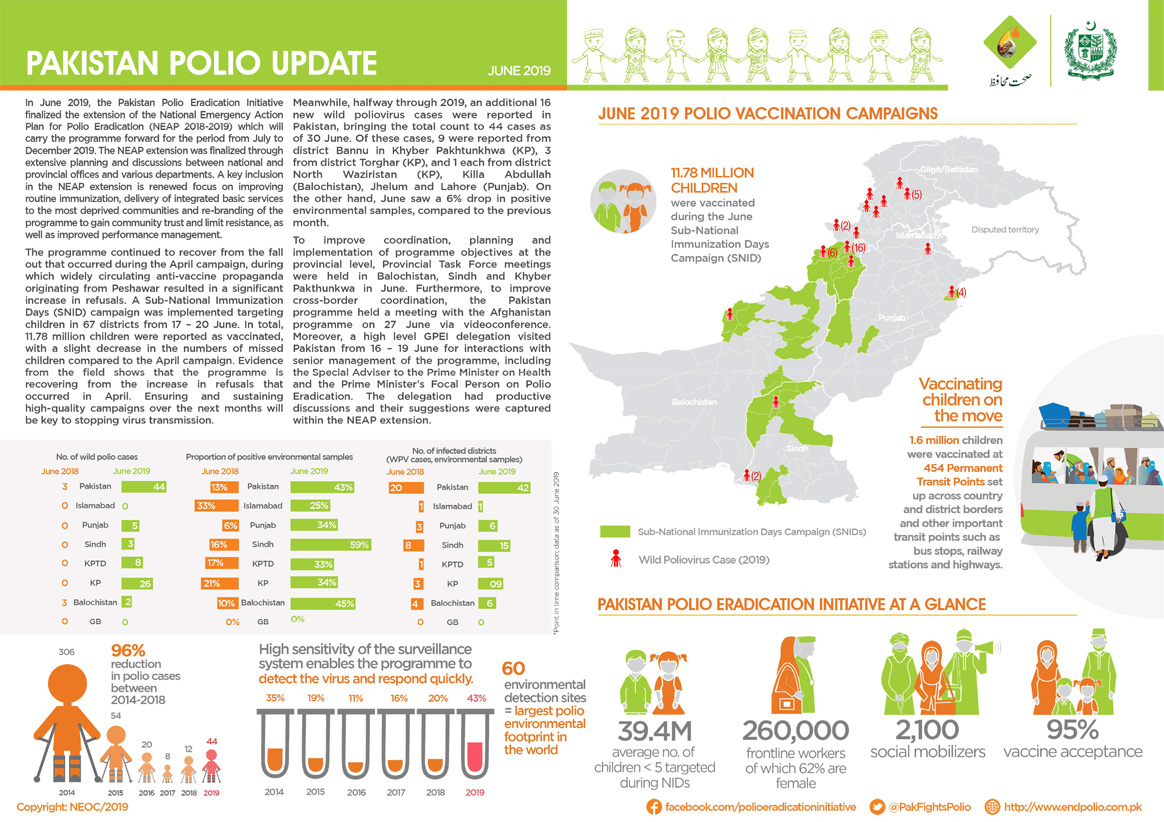

In May

“Our area is a pretty difficult terrain because we live in the water and it is not easy for the teams coming from outside the community to gain access. So, the (hand-drawn) maps make it possible for us to identify areas we have yet to reach during the immunization exercise”, says Peter Idowu, a veteran community mobilizer and team supervisor in Makoko — a riverine shanty town located on the coast of mainland Lagos city, southwest Nigeria. Native to the village, Peter is the man to go to whenever the polio immunization teams face challenges navigating the waterways or the community.

The sprawling water city Makoko is a slum located across the Third Mainland Bridge on the lagoon. It is a largely low-income community with half the population on water and the other half on land. Informal, makeshift houses with corrugated iron roofs sit precariously atop stilts. Down below, narrow wooden boats act as a form of aquatic taxi ferrying goods and people around the bustling community. Nobody knows the exact population of this slum district of Lagos, but it is estimated to be as high as 100 000. It is mostly a fishing community inhabited by the Egun people.

“My goal is to see that all the kids in our community are immunized and live healthy lives. That is why I engage our teams in sensitizing parents all the time on the importance of routine immunization and the dangers of polio. As a member of the community and with a passion of becoming a health worker myself, I kept on mobilizing our people for easy accessibility, because our language is different from Yoruba and most of the Polio teams can’t speak the language. It is always easy with me being in the Polio team as our people will readily accept the vaccine without rejecting,” says Peter.

Nigeria is the only country in Africa and one of the only three in the world endemic to wild poliovirus, alongside Afghanistan and Pakistan. Nigeria is also affected by circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) outbreaks.

UNICEF works closely together with Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), key polio partners and the Nigerian government. There is a vast network of over 20 000 community mobilizers focusing on demand creation and improving health-seeking behaviors of caregivers.

“We had not seen vaccination teams in our community for a very long time. Sometimes we go for months without vaccinating our children, if we don’t take our children to the mainland to get them vaccinated”, says Mr. Atebakuro Oton George, a fisherman and father of five, residing in Minibie ward of Nigeria’s Bayelsa State.

A largely riverine state, Bayelsa accounts for over 60% of the delta mangrove of the Niger Delta. Many children here continue to miss their chances at life-saving vaccination, as transport is precarious in the tangle of creeks and rivers that crisscross the state. In 2018 a number of innovative strategies such as, immunization boats at sea and community engagement through the traditional hierarchy and sensitization activities, supported by World Health Organization (WHO) through the Government of Bayelsa were introduced to reach a wider net of children.

“Now on weekly basis, health workers brave the seas and visit our communities to vaccinate our children”, an elated Mr. George continues.

Subsistence farming and fishing are the mainstay of the local population’s economy and diet. Health services are provided by primary health care centers located within the island communities.

“The difficulty of accessing healthcare services is due to suboptimal and expensive coastal and waterway transportation from the distant communities to healthcare centers, hence, innovative strategies are being employed to reach the underserved and vulnerable population with vaccination and other health interventions especially during Supplemental Immunization Activities (SIAs)”, says Dr Edmund Egbe, WHO State Coordinator in Bayelsa.

To reach ‘missed’ children, community engagement activities to increase demand for immunization have been initiated to bolster willingness of caregivers to readily access the interventions even when in the middle of the river or the ocean. The successful implementation of the community engagement framework has resulted in high-level acceptance of immunization services in the State. From April 2018 to April 2019, over 169 836 children received vaccination.

Routine immunization coverage has improved remarkably: the first quarter RI Lot Quality Assurance Survey (LQAS)— a quarterly activity organized by the National Emergency Routine Immunization Coordinator Centre (NERICC) to assess routine immunization performance, reasons for non-immunization as well as efforts to improve uptake and utilization of RI in Nigeria—conducted in April 2019 indicate that the State is second best in the country. Previously, the State was ranked amongst others in the country as poor-performing from the last National Immunization Coverage Survey (NICS) conducted in 2016; this led to the inauguration of an emergency response committee in March 2018.

King Diete-Spiff, the Chairman and the ‘Amanayanbo’ of Town-Brass, in his meeting with the State Traditional Rulers Council said, “Sustaining the innovative strategies of vaccinating vulnerable populations will undoubtedly increase immunity against vaccine preventable diseases and reduce the mortality and morbidity rate in difficult to access communities”. He described the polio infrastructure in Bayelsa, supported by WHO and partners, as the bedrock of driving successful healthcare intervention at the grassroots.

Support for polio eradication and routine immunization to Nigeria through WHO is made possible by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Department for International Development (DFID – UK), the European Union, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the Government of Germany through KfW Bank, Global Affairs Canada, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Rotary International and the World Bank.

A legion of supporters across neighbourhoods, schools, and households are creating a groundswell of support for one of the most successful and cost-effective health interventions in history: vaccination. These are everyday heroes in Pakistan’s fight against polio.

These thousands of brave individuals are championing polio vaccine within their communities to enlist the majority in the pursuit of protecting the minority — reaching the last 5% of missed children in Pakistan.

One of the major factors that determines whether a child will receive vaccinations is the primary caregiver’s receptiveness to immunization. The decision to vaccinate is a complex interplay of various socio-cultural, religious, and political factors. By educating caregivers and answering their questions, these Vaccine Heroes serve as powerful advocates for vaccination, even creating demand where previously there might have been hesitation. This is where everyday people step in to vouch for vaccination as a basic health right.

Here are some nuanced, powerful, and thought-provoking testimonies on their unwavering belief in reaching every last child:

In April

The sun often beats down on the humid forest corridors of Papua and West Papua—the easternmost provinces of Indonesia, thick with jungles and winding rivers with populations spread wide and far under these green canopies. Coupled with sketchy phone signals and the fact that electricity has yet to reach most parts of the two neighbouring provinces, a perfect storm was brewing, as poliovirus could sneakily circulate in ripe conditions.

On 8 February 2019, after extensive field investigations, Indonesia reported circulation of vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1 (cVDPV1) in Yahukimo District, Papua Province. A polio outbreak was officially declared.

Driven by the guiding ethos of reaching every last child, local public health authorities supported by the Global Polio Eradication Initiative have developed outbreak zone service delivery strategies to reach as many children as possible including at schools, at outreach and local health centres, door-to-door campaigns, or at churches and mosques.

Here are some inspiring testimonials and stories of the collective efforts to end the cVDPV in Indonesia:

Fasting? No problem

Mirnawati and Imelda are two ambitious immunization staff members at the Moswaren health centre in the South Sorong District of West Papua province. Once the mass immunization campaigns began in their district on 29 April, Mirnawati and Imelda headed to their local community school to vaccinate all children from ages 5-15 years.

Upon contacting the school administration, they realized that the school session would be out for a week-long break, right up to the beginning of the month of Ramadan—a period of fasting for the Muslim population in the community.

Thinking quickly and willing to accommodate the Muslim students, both the immunization officers quickly coordinated with the school principal to offer vaccination on the National Education Day ceremony on 2 May. Mirnawati and Imelda also went above and beyond by offering to stay past sun-down to vaccinate all Muslim students after they opened their fasts.

Adrian, 7 years old

“Hello, my name is Adrian Suu. I am 7 years old, and I am from Cenderawasih village in Yahukimo, Papua Province. I study in the first grade at the Lentera Harapan School, and I want to be a pilot when I grow up. I’m glad that I got vaccinated so I can be healthy and fly in a plane!”

The resurgence of poliovirus in Indonesia underscores the threat posed by low-level virus transmission and the need to maintain high routine immunization everywhere in the world to minimize the risk of circulation of the virus.

The first polio outbreak response rounds were conducted in March and April 2019, targeting around 1 million children each in Papua and West Papua provinces. While the immunization coverage has been high across West Papua and low-land districts of Papua, vaccine coverage has often been impeded in high-land districts, including the outbreak source—Yahukimo district – owing to mobile populations, dense forests and poor health infrastructure.

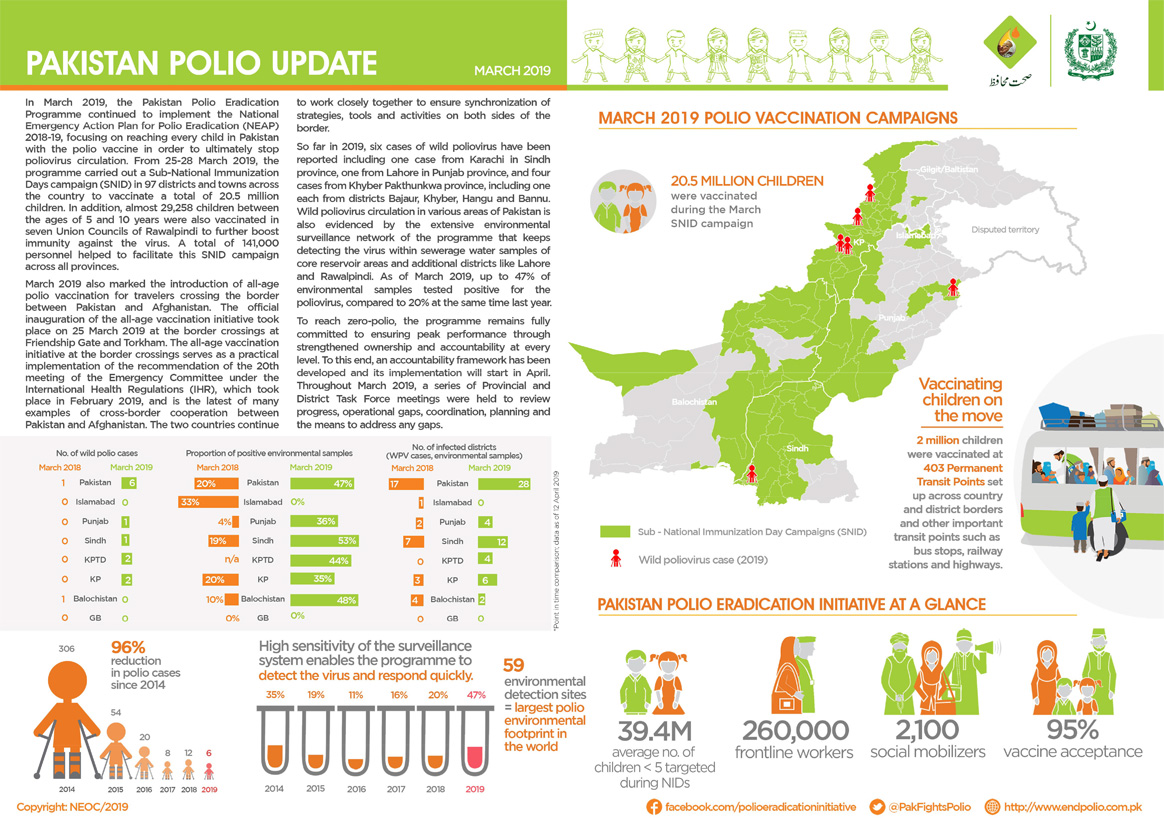

In March:

On both sides of the historical 2640-kilometre-long border between Pakistan and Afghanistan, communities maintain close familial ties with each other. The constant year-round cross border movement makes for easy wild poliovirus transmission in the common epidemiological block.

As a new tactic in their joint efforts to defeat poliovirus circulation, Afghanistan and Pakistan have introduced all-age polio vaccination for travellers crossing the international borders in efforts to increase general population immunity against polio and to help stop the cross-border transmission of poliovirus. The official inauguration of the all-age vaccination effort took place on 25 March 2019 at the border crossings in Friendship Gate (Chaman-Spin Boldak) in the south, and in Torkham in the north.

Although polio mainly affects children under the age of five, it can also paralyze older children and adults, especially in settings where most people are not well-immunized. Adults may play a role in poliovirus transmission, so ensuring that they have sufficient immunity is critical to simultaneously eliminating poliovirus from the highest risk areas on both sides of the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

This is particularly important at the two main border crossing points – Friendship Gate and Torkham – given the extensive amount of daily movement. It is estimated that the Friendship Gate border alone receives a daily foot traffic of 30 000. Travellers include women and men of all ages, from children to the elderly.

Pakistan and Afghanistan first increased the age for polio vaccination at the border in January 2016, from children under five years to those up to 10 years old. The decision was in line with the recommendations of the Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations (IHR) which declared the global spread of polio a “public health emergency of international concern”,

The all-age vaccination against polio at the border crossings serves a practical implementation of another recommendation of the IHR Committee: that Pakistan and Afghanistan should “further intensify crossborder efforts by significantly improving coordination at the national, regional and local levels to substantially increase vaccination coverage of travelers crossing the border and of high risk crossborder populations.”

As part of the newly introduced all-age vaccination, all people above 10 years of age who are given OPV at the border are issued a special card as proof of vaccination. The card remains valid for one year and exempts regular crossers from receiving the vaccination again. Children under 10 years of age will be vaccinated each time they cross the border.

Before all-age vaccination began at Friendship Gate and Torkham, public officials held extensive communication outreach both sides of the border to publicize the expansion of vaccination activities from children under 10 to all ages. Radio messages were played in regional languages, and community engagement sessions sensitized people who regularly travel across the border. Banners and posters were displayed at prominent locations.

Deputy Commissioner for Khyber District in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Mr Mehmood Aslam Wazir, inaugurated the launch of All-Age Vaccination by vaccinating elderly persons at the Torkham border crossing. “Vaccination builds immunity and it is necessary for children to be vaccinated in every anti-polio campaign. The polio virus is in circulation and could be a threat to any child. The elders in our community could be carrier of the virus and take along the virus from one place to another, therefore, vaccination of every traveller, of all ages and genders, crossing Pakistan-Afghanistan border will be the key determinant to interrupt polio virus transmission in the region, and the world.”

The introduction of the all-age vaccination at border crossings is the latest example of cross-border cooperation between Pakistan and Afghanistan. The two countries continue to work closely together to ensure synchronization of strategies, tools and activities on both sides of the border.

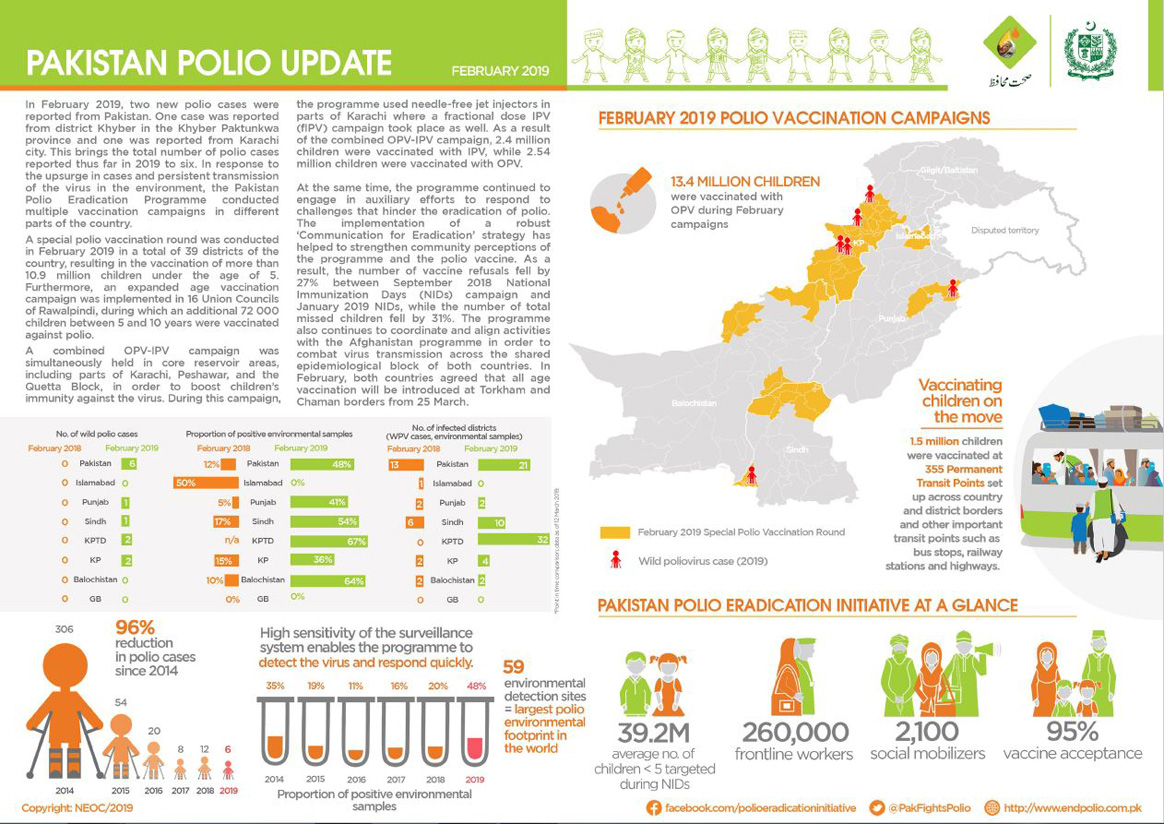

In February:

In February:

Thanks to the unbending resolve and resilience of women health professionals as they go door-to-door across villages and mountains administering vaccine in some of the most marginalized or remote communities, women are truly the backbone of the polio programme at the ground-level. We asked a few of these women about their most daunting and heartening moments in polio, and how they worked through them.

Julia Kimutai—Community Strategy Coordinator Nairobi, Kenya

For Julia Kimutai, a 38-year-old community strategy coordinator in Kenya, educating the public about the importance of vaccines is a constant project. As a specialist in dense urban areas with high rise buildings, Julia knocks on a lot of doors and is often greeted with refusals.

“To convince some mothers is not easy,” she says. “It has never been a smooth ride.”

But where some might just see a campaign-time encounter with skeptical parents as a one-off, Julia sees a long-term project.

“Where we have difficulties is where we double down our efforts to build relationships. We even go back when there is no polio campaign to try to talk with parents, emphasize why vaccination is important and try to do a lot of health education,” she says.

As a woman and as a mother, Julia believes she is uniquely qualified as she can relate, understand and convey the importance of polio vaccines to the numerous apprehensive mothers she meets daily.

“I am a good listener, a good communicator and patient. These tools help me daily as Polio Eradicator and a mother.”

Asha Abdi Dini—District Polio Officer, Banadir, Somalia

A district polio officer with over two decades of experience in Banadir, Somalia, for Asha Abdi Dini, refusals are always heartbreaking. “My worst moment was seeing a family who had three girls and a son. They vaccinated their daughters but refused to allow the boy to take the vaccine. The boy got the polio and the girls survived.”

But Asha takes pride in the challenges she has been able to overcome since joining the polio programme.

“My best moment is seeing the same children I once vaccinated all grown up and bring their own children for vaccinations. It gives me immense hope and happiness,” she says.

Bibi Sharifa—Health Communication Support Officer, Islamabad, Pakistan

A continent away, for 39-year-old Islamabad district health communication support officer, Bibi Sharifa, a big part of the job is demonstrating how women can do difficult work and stand firm in the face of adversity.

“People often think that women are incapable, but they really couldn’t be more wrong. The women on our programme are extraordinary – they are strong, gentle, dedicated, humble, passionate, disciplined and fierce at the same time,” she says. “They are driven by the love of their children and their community, and despite the challenges they face, people should realize that women are like grass, not like trees: where trees can be uprooted by floods, grass can face the brunt of flood easily.”

Like many Pakistani women, Hafiza and Sahiqa start their days in the early morning, when other household members are still asleep. They tackle their domestic chores before beginning their official duties – as polio frontline workers.

“I get up by 5:00 am, if I am to prepare properly for a productive day. I need to manage my home chores before I can set out for my official work. I have to prepare breakfast, lunch, lunch boxes for my children and do the dishes. After that I clean the house and then I have to prepare my kids for school. After sending them to school, I leave for the office around 7:30 am,” Sahiqa explained.

Sahiqa (29) is from Quetta in Balochistan province and Hafiza (22) is from Islamabad. In their careers as Pakistan’s cadre of Lady Health Workers, they deliver house-to-house preventative and curative care to underserved communities, in particular women and children in urban and rural slum areas Locally recruited and community-based, these female health workers are also central to progress against polio in Pakistan’s complex environment.

Across Pakistan, thousands of women do the vital work of immunization in an environment that can be harsh, distressing and even dangerous. They balance this work with the demands of their own children and families, and they put their own needs last.

The women’s official workday starts at 8:00 am and is marked by interactions with the community every day. As part of their work, Lady Health Workers educate women about the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, on better hygiene practices, supporting the advancement of women and children’s health and wellbeing. They knock on every door of their assigned areas to vaccinate children against polio during frequent immunization campaigns.

In Pakistan, women currently make up more than 56% of more than 260 000 frontline polio workers. Having women on the frontlines has been a game changer for polio eradication in Pakistan, given the trusted roles they have in communities and the fact that they are more likely to be allowed to take the crucial step across the thresholds of people’s homes and ensure access for all children to vaccines. Female polio frontline workers including vaccinators, campaign coordinators, supervisors and social mobilizers often work in extremely challenging circumstances to ensure children are protected against polio.

“I remember one chronic refusal family. It was such a difficult task to convince the women of the house to vaccinate their children. We engaged in many discussions and I explained to them that if the polio drops were not beneficial, would I give them to my own kids?

After a lot of convincing, I was able to persuade the women. I was so happy to have managed to convert a chronic refusal case and protect the kids in that house against polio,” Sahiqa said.

Despite multiple challenges, especially working in a conservative province like Balochistan, the health workers remain steadfast and intensely committed when it comes to achieving their goals. They have become creative problem solvers who are motivated by every refusal they convert. The challenges act as fuel and have helped them develop the skills they need to navigate the complexities of the job in this cultural context.

“While performing my job, remaining calm and controlling my emotions are the most difficult skills that I have drawn from these challenges. During this job, I learnt a lot how to avoid taking things personally as this helped me focus on the real objective. With the passage of time, I have realized the importance of maintaining firm boundaries in order to facilitate respectful communication with people,” said Hafiza.

There are different reasons why women in Pakistan make the choice to become polio frontline workers. Some have to support their families and some have to earn money for their studies. Many women take this job because it is the best opportunity to move ahead in life. The defining characteristic of most female polio frontline workers is a passion to serve humanity.

“I feel lucky to have my husband beside me, supporting me in every endeavour. He is also a polio worker and he feels that women have better access to the homes in the communities and can relate to the mothers therefore they have a definite advantage in gaining the trust of the homemakers in the community,” Sahiqa said.

The women’s official duty ends with the setting sun, but at home domestic responsibilities await. They have to prepare dinner for the family and then help children complete homework. The idea of eight hours of uninterrupted sleep is a dream for them, but they sleep with the knowledge that they are doing important work, and doing it well.

Hafiza and Sahiqa are individual women, but they are also a reflection of every female worker who is part of the fight against polio. The polio eradication programme would not be where it is today without the contributions of hardworking women dedicated to ending polio.

If you ask the women who work in Somalia’s polio programme why they do what they do, most will tell you they do this to help Somali children, to build a stronger future for Somalia, and to support their own families. Somalia is a complex country with many cultural and institutional challenges for women who work outside the home. Perhaps, as a result, there is a sense of solidarity among the women to pull each other up and work together in the fight against polio.

From the senior member of the polio programme to the district-level polio officer (who chooses to remain anonymous for her own security), and for so many women in between, being part of the polio programme is not just a job, but a way to work together and support each other.

Dr Rehab Kambo—International Focal Point and Head of the Polio Programme, The World Health Organization, Garowe, Somalia

Dr Rehab Kambo wears two hats at The World Health Organization (WHO): International Focal Point and Head of the Polio Programme in the satellite office at Garowe, Puntland state of Somalia. After joining the polio programme, Dr Rehab set out to understand the context she was working in and one of the things she learned was about the strength of Somali women.

“It is easy not to notice that Somali women are stronger than men in their society, until you spend time with them,” she said.

For Dr Rehab, this realization was driven home on an early assignment. She and a colleague were conducting a surveillance review in a region known as Mudug. Dr Rehab had traveled to Galkacyo by road for eight hours during an active clan conflict, which was no easy feat. Movement was challenging, and the women had to travel with armed escorts. But they were determined, Dr Rehab explains, and they were on a mission.

The two visited transit points at the airport and health facilities to meet with Village Polio Volunteers, who serve the polio eradication initiative at the district level. Upon completing the mission, she and her colleague were elated. Dr Rehab looks back on this as one of the most satisfying – albeit stressful – experiences of her life as a polio eradicator.

Since then, Dr Rehab has taken on the challenge of two roles in one of the most operationally demanding regions in the world. For Dr Rehab inspiration comes easily from the women around her.

“In many instances, they are powerful, independent, and are decision-makers in their families,” said Dr Rehab of the Somali women. Even as a relatively privileged, educated woman, Dr Rehab admits there is a lesson in here for her, and for other women like her.

“Women are so strong, honestly. They can adapt to any role for the good of others,” she said.

Mira A—District Polio Officer, Somalia

Life in Somalia has been extraordinarily difficult since war broke out in 1991, and there is no doubt that it has been harder for women than for men. With an average fertility rate of 6.6 per woman, and high death rates in mothers – one out of every 12 women dies due to pregnancy complications – women are in need of timely and quality health services. A lack of education compounds the problem.

“Despite the challenges, women in Somalia have resiliently stood up to the task and engaged in small-scale businesses over the years to earn a living for their families,” said Mira A, a District Polio Officer in Somalia (we are not using her real name for security reasons).

For Mira A and women like her, taking work outside the home is a way to support not just their families, but themselves – and each other.

“Many women have no time to continue their education or look for other jobs, as they are so busy trying to earn money with their existing means,” she said.

When Mira A looks at the women around her, she sees that education is only part of the answer.

“There is a small sector of women who have managed to earn formal education, but even they do not earn money in most cases. They stay at home and look after their homes and children. Even they need to be empowered, even if it is just to help other women.”

Polio eradication efforts are as much rooted in the social realities as they are in the technological tools. The success of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative comes down to one simple action: the knock on the door, when the child’s caregiver greets the health worker.

Why do caregivers let vaccinators enter their homes? The caregiver’s decision to vaccinate is influenced by many moving parts: social, cultural, economic, and religious. Women health workers and leaders are able to transcend many of these boundaries as they are not only health workers; they are members of that community – someone’s neighbour, friend, aunt, cousin or grandmother.

Polio-endemic, at-risk, and outbreak countries regularly engage women as health officials in immunization activities, constituting about 68% of the frontline workforce. In Nigeria, 99% of frontline workers are women, followed by 56% in Pakistan and 34% in Afghanistan. But their strength in numbers is not the only reason why women are crucial to polio eradication efforts, they are, in fact, behavioural change agents.

Here’s a look at some of the resilient and inspiring women working to eradicate polio in their communities – in their own words:

Reposted with permission from Rotary.org

Dr Ujala Nayyar dreams, both figuratively and literally, about a world that is free from polio. Nayyar, the World Health Organization’s surveillance officer in Pakistan’s Punjab province, says she often imagines the outcome of her work in her sleep.

In her waking life, she leads a team of health workers who crisscross Punjab to hunt down every potential incidence of poliovirus, testing sewage and investigating any reports of paralysis that might be polio. Pakistan is one of just two countries that continue to report cases of polio caused by the wild virus. In addition to the challenges of polio surveillance, Nayyar faces substantial gender-related barriers that can hinder her team’s ability to count cases and take environmental samples. From households to security checkpoints, she encounters resistance from men. But her tactic is to push past the barriers with a balance of sensitivity and assertiveness.

“I’m not very polite,” Nayyar says with a chuckle. “We don’t have time to be stopped. Ending polio is urgent and time-sensitive.”

Women are critical in the fight against polio, Nayyar says. About 56% of frontline workers in Pakistan are women. More than 70% of mothers in Pakistan prefer to have women vaccinate their children.

That hasn’t stopped families from slamming doors in health workers’ faces, though. When polio is detected in a community, teams have to make repeated visits to each home to ensure that every child is protected by the vaccine. Multiple vaccinations add to the skepticism and anger that some parents express. It’s an attitude that Nayyar and other health workers deal with daily.

“You can’t react negatively in those situations. It’s important to listen. Our female workers are the best at that,” says Nayyar.

With polio on the verge of eradication, surveillance activities, which, Nayyar calls the “back of polio eradication”, have never been more important.

Q: What exactly does polio surveillance involve?

A: There are two types of surveillance systems. One is surveillance of cases of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP), and the second is environmental surveillance. The surveillance process continues after eradication.

Q: How are you made aware of potential polio cases?

A: There’s a network of reporting sites. They include all the medical facilities, the government, and the hospitals, plus informal health care providers and community leaders. The level of awareness is so high, and our community education has worked so well, that sometimes the parents call us directly.

Q: What happens if evidence of poliovirus is found?

A: In response to cases in humans as well as viruses detected in the environment, we implement three rounds of supplementary immunization campaigns. The scope of our response depends on the epidemiology and our risk assessment.

We look at the drainage systems. Some systems are filtered, but there are also areas that have open drains. We have maps of the sewer systems. We either cover the specific drainage areas or we do an expanded response in a larger area.

Q: What are the special challenges in Pakistan?

A: We have mobile populations that are at high risk, and we have special health camps for these populations. Routine vaccination is every child’s right, but because of poverty and lack of education, many of these people are not accessing these services.

Q: How do you convince people who are skeptical about the polio vaccine?

A: We have community mobilizers who tell people about the benefits of the vaccine. We have made it this far in the program only because of these frontline workers. One issue we are facing right now is that people are tired of vaccination. If a positive environmental sample has been found in the vicinity, then we have to go back three times within a very short time period. Every month you go to their doorstep, you knock on the door. There are times when people throw garbage. It has happened to me. But we do not react. We have to tolerate their anger; we have to listen.

Q: What role does Rotary play in what you do?

A: Whenever I need anything, I call on Rotary. Umbrellas for the teams? Call Rotary. Train tickets? Call Rotary. It’s the longest-running eradication program in the history of public health, but still the support of Rotary is there.

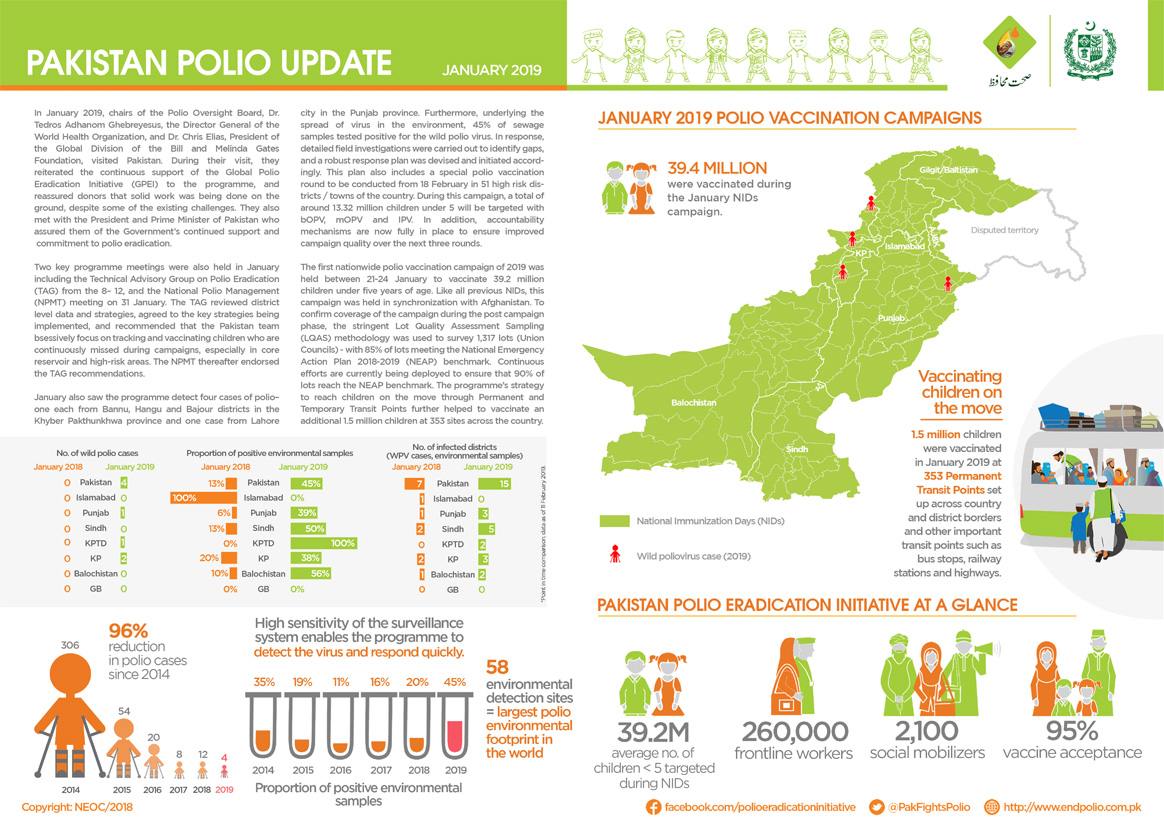

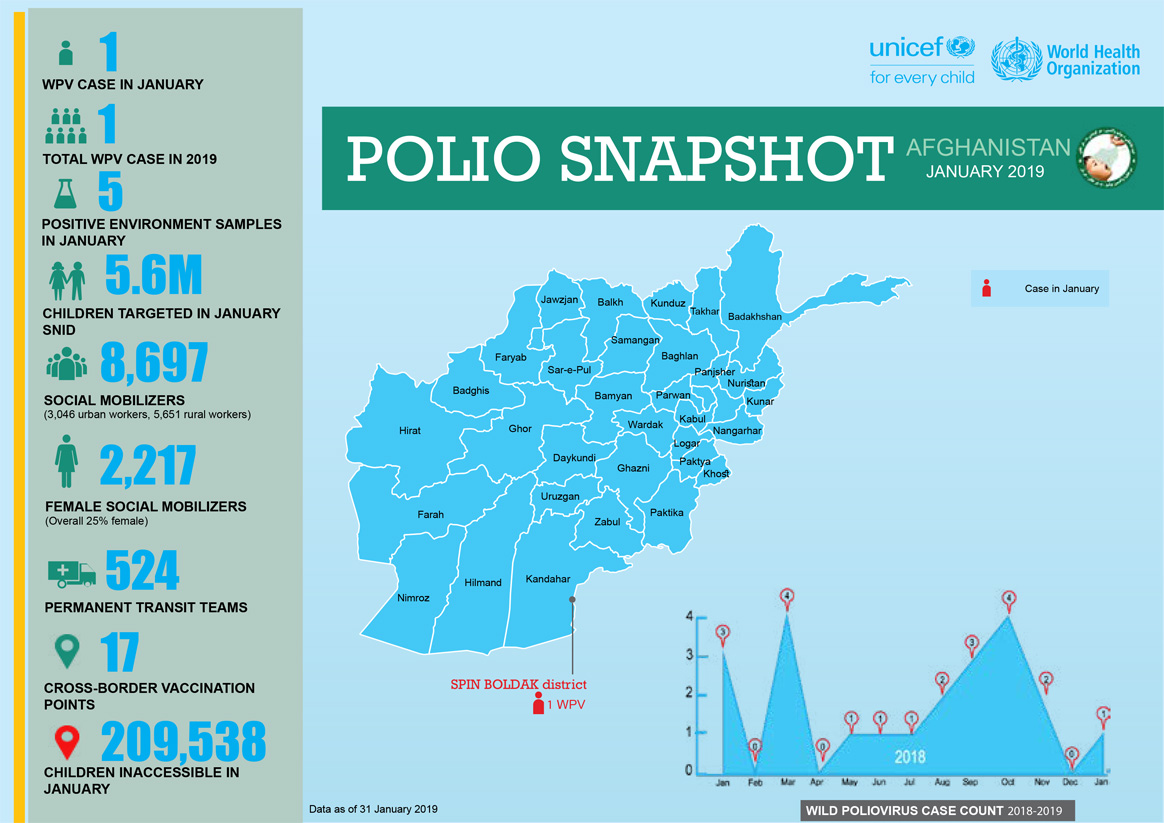

In January:

Pakistan’s polio programme relies on the efforts of thousands of specialized workers, but there is one group almost everyone relies on: the drivers.

In the endgame of eradication, reaching zero transmission requires a vast network of expertise— from epidemiologists to community advocates to data managers and health workers. But without drivers, many of these people would not be able to do their work.

Polio eradication entails wide-ranging nationwide vaccination campaigns. In Pakistan, this means targeting more than 38 million children under the age of five. Reaching every single child without an organized fleet of vehicles is almost impossible. Polio programme drivers do not plan activities in operations centres, but they have a real on-ground impact in the fight against polio.

“ I think whether you are a polio eradication officer, data personnel, technical staff, a consultant, a member of the communication team or a driver, every single employee is playing a very significant role in polio eradication efforts.”

Bahudar Shah (53), Islamabad, Pakistan

“It doesn’t matter whether you’re in the driver’s seat or the passenger seat, driving is an unavoidable and essential part of the polio programme, especially here in Pakistan, where the push for eradication is at such a sensitive and critical point. I have spent the last 20 years as a driver with WHO’s polio programme, always with the same focus: saving Pakistani children from this disease and securing a better future for them.”

“For polio field officers, duty starts around 8 am, but the driver’s duty starts early in the morning whether they are traveling directly to field or to the office. I personally feel that when I am in the field, I am responsible for the safety of my assigned vehicle as well as that of the officer.”

Alam Sher Khan (52), Islamabad, Pakistan

“I joined in 2002 and since then I have learned, I am working for the welfare of future generations. At work, I apply the “safety first” approach to every part of my job. I think, I am not only driving but I also act as a guide and security guard for my field officer. Because I drive with different field officers at different places, before the commencement of field work I orient my officer about the social norms, customs and security situation of the area. I also advise them to remain close to the vehicle. It is very essential to remain close to the vehicle for a possible quick escape in case of some emergency situation.

“The thing I enjoy as a driver with the polio programme is the satisfaction of my passenger: the field officer. When my field officer is satisfied, I am satisfied, and for this I have worked to enhance my skills.”

Ghulam Asghar (59), Islamabad, Pakistan

“For the last 16 years, I have played a significant role in polio eradication in Pakistan. My level of responsibility as a driver is very high. Polio eradication is a programme that requires strong teamwork. While performing my duty with different field officers, I assist them in finding local vaccination teams and convincing the community of the importance of vaccination, and I clear any hurdles so they can do their jobs during case investigation, campaign monitoring and LQAS.

“When my officer covers refusals during campaign monitoring, it gives me the most satisfaction as I feel that we have saved a child from permanent disability. When there is some refusal I actively assist my officer to counter that refusal. I also advocate within my local community and try to satisfy them about the efficacy of the vaccine.”

Jamil Abbasi (46), Islamabad, Pakistan

“I have been a driver for the polio programme for the last 14 years. I think whether you are a polio eradication officer, data personnel, technical staff, a consultant, a member of the communication team or a driver, every single employee is playing a very significant role in polio eradication efforts.

“I have a strong wish to see Pakistan polio free. Although I am not directly involved in eradication activities, indirectly I am contributing to better implementation and success of routine immunization efforts by safely transporting field officers to their assigned duty areas. I am proud that I am a part of hardworking team who are trying to defeat the polio virus.”

In January

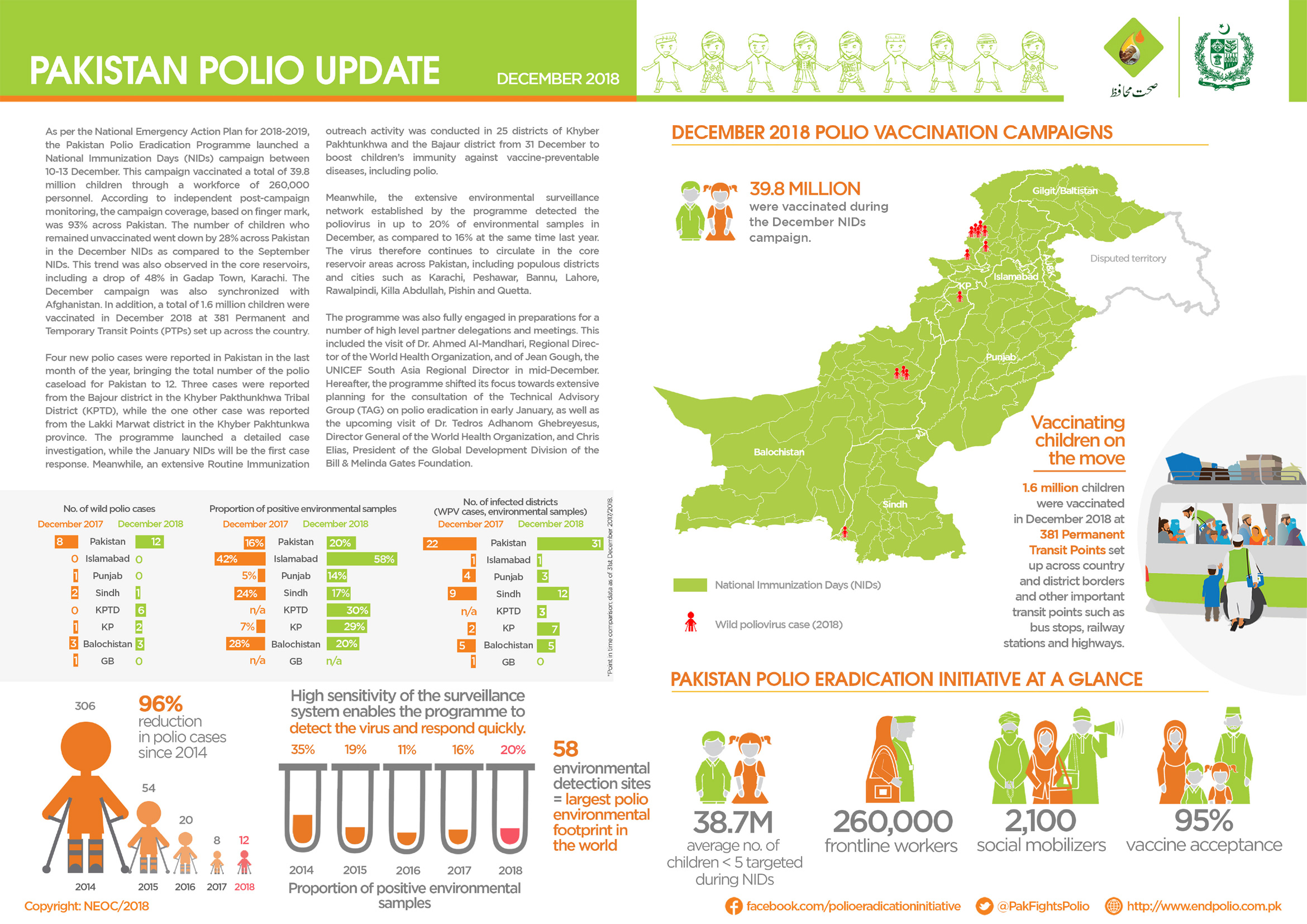

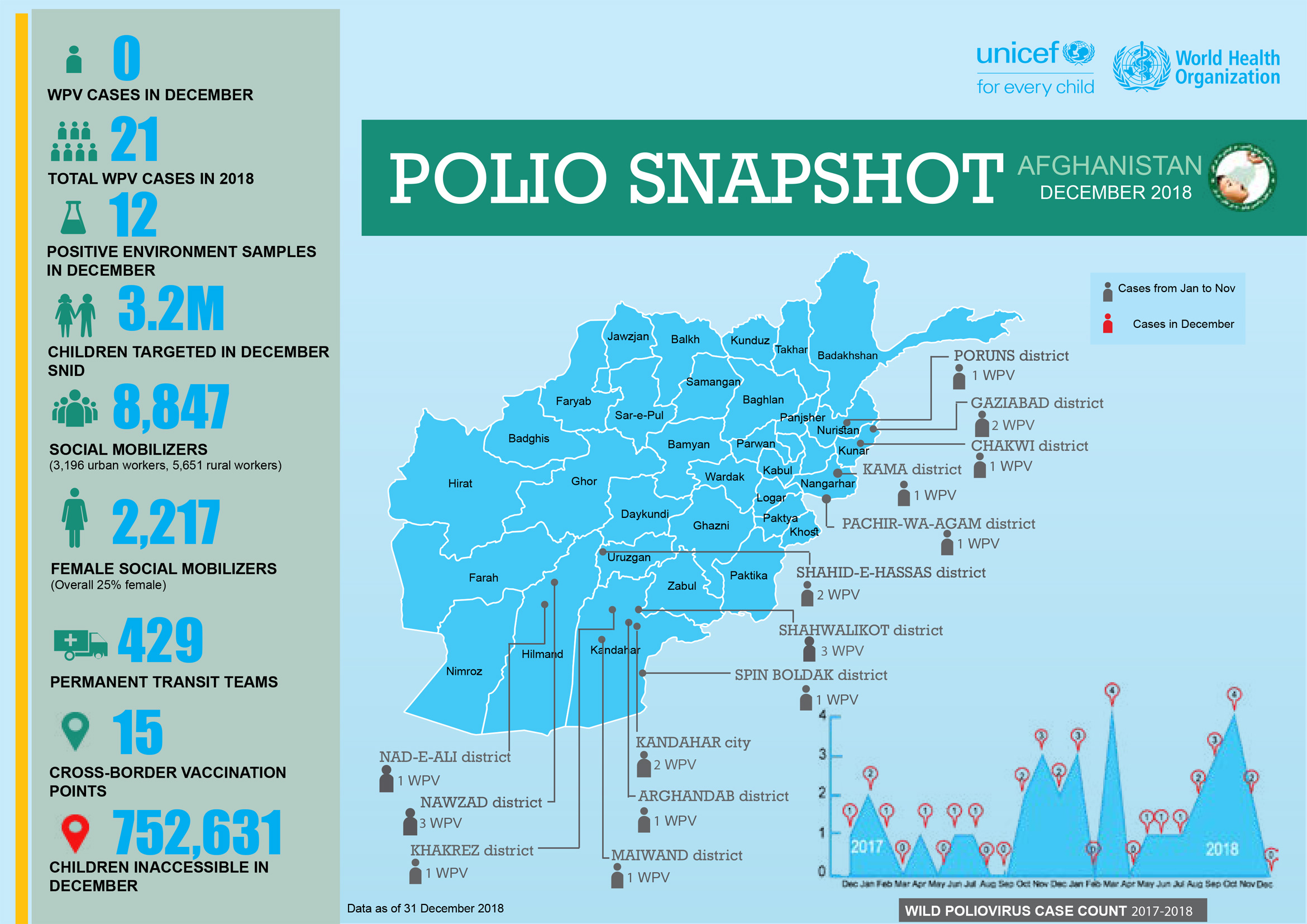

In December

In December

A new circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) outbreak has been confirmed in Mozambique. Two genetically-linked circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) isolates were detected from an acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) case (with an onset of paralysis on 21 October 2018, in a six-year old girl with no history of vaccination, from Molumbo district, Zambézia province), and a community contact of the case.

As polio is a highly infectious disease which transmits rapidly, there is potential for the outbreak to spread to other children across the country, or even into neighbouring countries, unless swift action is taken. Global Polio Eradication Initiative and partners are working with country counterparts to support the local public health authorities in conducting a field investigation (clinical, epidemiological and immunological) and thorough risk assessment to discuss planning and implementation of immunization and outbreak response.

In January 2017, a single VDPV2 virus had been isolated from a 5-year old boy with AFP, also from Zambézia province. Outbreak response was conducted in the first half of 2017 with monovalent oral polio vaccine type 2 (mOPV2).

Read our Mozambique country page to see information on cases, surveillance and response to the developing outbreak.

In November: