The discovery in the summer of 2022 that poliovirus had been found in sewers in London as well as in an unvaccinated community in New York startled many who had long forgotten about polio. The outbreak was a perfect demonstration that vaccines are often so successful at stopping deadly diseases, that we can be lulled into a false complacency.

Although the disease is now endemic only in Afghanistan and Pakistan, it was a dangerous childhood disease across the world for much of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although polio vaccines were introduced as routine immunisations in the 1970s, which reduced cases substantially, by the late 1980s, polio still was paralysing over 1,000 children a day.

In 1988, the launch of Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI, of which Gavi is a member) had a galvanising effect on efforts to eliminate the disease, bringing together governments, donors, local communities and health workers in a joint effort to raise awareness of the disease and widen access to polio vaccines.

Cases began to drop dramatically and are down 99%, with most countries having zero cases. An estimated 20 million children have been prevented from getting polio since the GPEI was launched. When Nigeria was declared free of wild poliovirus in 2020, it was a major achievement: it had been one of the last few countries where the disease had clung on.

As remarkable as these successes have been, polio experts warn that there is no room for easing off on eradication efforts until the world is polio-free. Infectious diseases that are nearly wiped out can bounce back with alarming ease when the global circumstances change – measles rates have started climbing in the past few years as vaccination rates have fallen in Europe and the US.

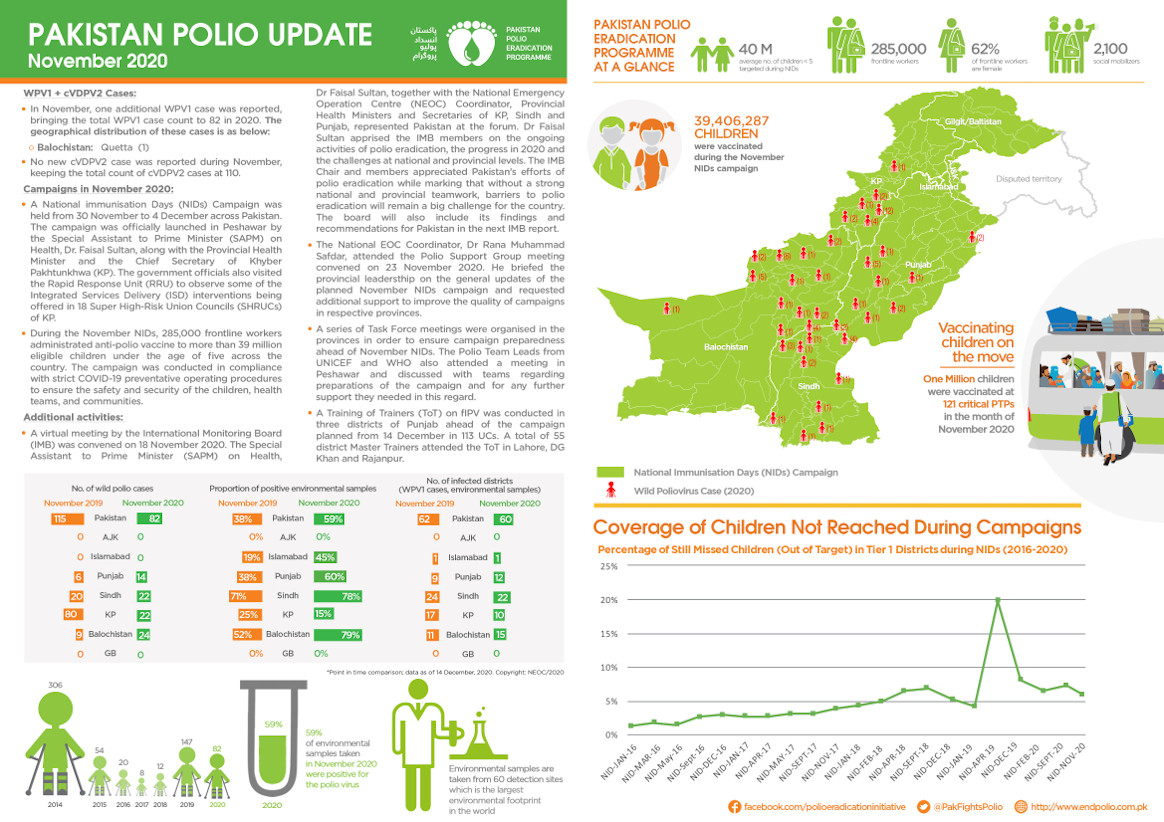

Uneven polio vaccine coverage across the world, compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic’s toll on routine immunisation worldwide, has meant the disease has popped up in unexpected places. In October 2021, Ukraine saw an outbreak, followed by a case of wild poliovirus in February 2022 in Malawi. In March, vaccine-derived polio was spotted in Israel, and in Pakistan, where the disease is still entrenched, more polio cases were recorded in the first quarter of 2022 than in the whole of 2021.

Although polio only affects a handful of countries currently, the potential threat from its continued circulation means that the World Health Organization still classifies it as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) despite this classification being given back in 2014.

An ancient disease

Polio is one the world’s oldest diseases – 14th century Egyptian engravings have been found depicting a priest with a withered leg, the trademark of a disease that can paralyse the leg, leading to muscle weakness and shrinking. The British physician Michael Underwood produced the first clinical description of the disease in 1789. In 1840, the German orthopaedic doctor Dr Jacob Von Heine understood that poliomyelitis was a distinct disease from other forms of paralysis and theorised it had an infectious cause. The poliovirus that causes the disease was identified in 1909 by Austrian immunologist Karl Landsteiner.

The disease is caused by a highly infectious virus that spreads when people ingest food or water contaminated by human faeces, or through poor hygiene. Because of this it is common in areas where there is poor access to clean water and sanitation.

The virus mostly affects children. Around 70% of infections are asymptomatic or cause mild symptoms such as headache, fever, and neck stiffness, but it can also invade the nervous system and cause paralysis and, in extreme cases when the person’s breathing muscles are paralysed, it can kill. In some survivors, the nerve damage can cause post-polio syndrome, a disorder in which they may have muscle weakness that deteriorates over time, causing pain and fatigue and leaving them disabled.

There are three wild types of poliovirus (WPV) – type 1, type 2, and type 3. Type 2 was declared eradicated in September 2015, with the last case detected in India in 1999. Type 3 was declared eradicated in October 2019, having last been detected in November 2012. Type 1 remains in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Vaccine development

There are two types of polio vaccines – an inactivated (killed) polio vaccine (IPV) developed by Dr Jonas Salk and first used in 1955, and a live attenuated (weakened) oral polio vaccine (OPV) developed by Dr Albert Sabin and first used in 1961.

IPV is made from inactivated wild-type poliovirus strains of each type; it is an injectable vaccine and in many countries is given with other routine childhood immunisations such as against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis.

OPV consists of a mixture of live attenuated poliovirus strains of each of the three serotypes. It is safe and effective, however, the use of OPV in areas with poor water and sanitation can occasionally have an unwanted side effect – the live vaccine-virus shed by vaccinated individuals can in very rare cases mutate and spread in communities that are not fully vaccinated against polio.

The lower the population immunity, the longer the vaccine-derived virus can spread. This version of the virus can sometimes regain its ability to damage the nervous system and lead to paralysis – this is called a circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV).

Although IPV is an effective vaccine and valuable in countries with zero incidence of polio, it is better used as a precaution, since it does not trigger the same immune response as OPV and therefore is not as effective in stopping active poliovirus transmission. OPV induces mucosal immunity in the intestine, the primary site where poliovirus replicates – in this way, the vaccine prevents shedding of the virus into the environment and can limit or stop person-to-person transmission. This is critical in communities with poor water and sanitation, where people are more likely to be exposed to water-borne pathogens.

Thus, although IPV has has recently been introduced into routine immunisation programmes in Gavi supported countries, OPV is still needed in countries where transmission needs to be stopped.

The last mile to eradication

The polio eradication effort was badly hit by the pandemic, but is now regaining ground. One new weapon in the arsenal is a new vaccine – the novel oral polio vaccine (nOPV2) – which has been modified to be more genetically stable than the Sabin strain and less likely to cause cases from vaccine-derived virus.

In November 2020, nOPV2 received a recommendation for use under WHO’s Emergency Use Listing (EUL) procedure to be able to roll it out rapidly. As of June 2022, approximately 370 million doses of nOPV2 have been administered in 20 countries – including Benin, Cameroon, Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tajikistan and Uganda.

The high demand for this vaccination, however, is causing a supply constraint that the GPEI is working to ease. The GPEI advises that in situations where there is co-circulation of poliovirus strains, trivalent oral polio vaccine (tOPV) may be the best choice of vaccine.

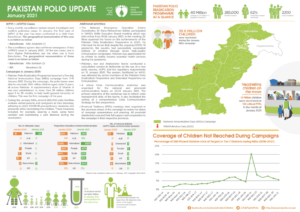

Considerable challenges remain in eradicating polio in the two endemic countries. In Pakistan, difficulties in accessing high-risk mobile communities remain, and this is exacerbated by people refusing to get their children vaccinated because of misinformation or community fatigue, as well as low routine immunisation coverage in some parts of the country.

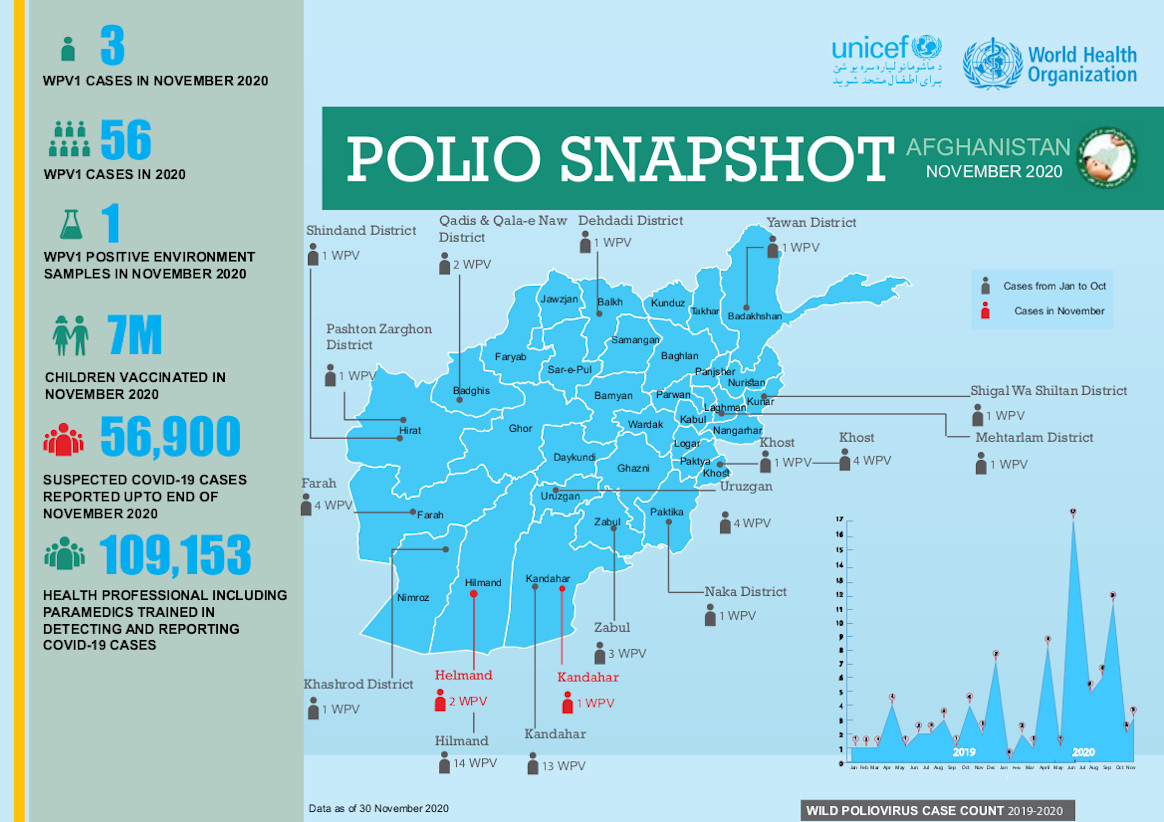

Afghanistan shares many of these challenges, including vaccine hesitancy, with the added challenge of decades of conflict and insecurity leading to fragile health systems that are unable to sustain routine immunisations. This has meant that many communities are missed or under-vaccinated, leaving children at risk of polio.

Now that polio vaccination programmes have resumed, eradication efforts have stepped up, ramping up vaccine coverage by boosting vaccine supply and engaging the trust of communities to overcome misinformation and raise awareness of the need for the vaccine, which can mean bringing in community and religious leaders.

The last mile to ending polio has been in sight for years, but the pandemic has thrown progress off course. While the road to eradication remains challenging, the ability of polio to re-emerge unexpectedly proves the need to continue to strive towards ensuring a polio-free world. For now, the disease is endemic in two low-income countries; there is no guarantee it will stay that way.

Reposted with permission from: www.gavi.org/vaccineswork

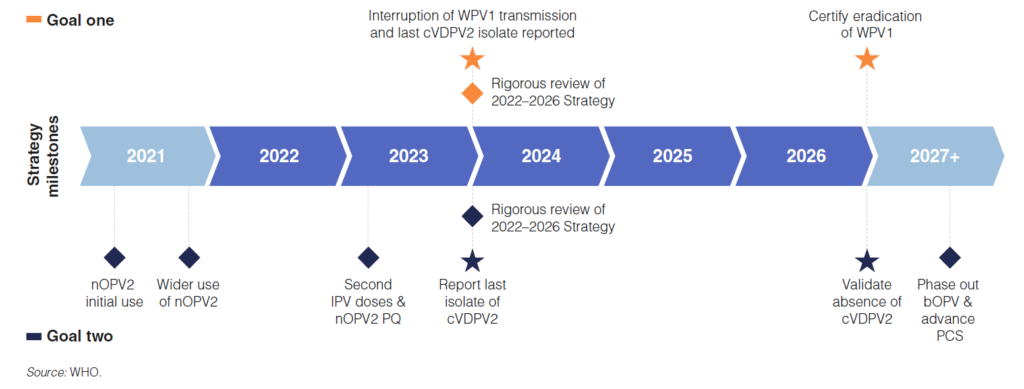

2023 is a critical year for the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). It is the target year to interrupt all remaining wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) and circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) transmission chains, per the GPEI

2023 is a critical year for the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). It is the target year to interrupt all remaining wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) and circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) transmission chains, per the GPEI