In 2011, a major endeavour was launched to develop a more genetically stable version of the monovalent oral polio vaccine type 2 (mOPV2) to more sustainably stop outbreaks of type 2 variant poliovirus. Fast forward to today, and close to 600 million doses of the novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2) have been used across 28 countries in outbreak response. We spoke to the co-leads of GPEI’s nOPV Working Group, Simona Zipursky (World Health Organization) and Ananda S. Bandyopadhyay (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation), to check in on how things are unfolding with deployment and use of this innovative tool.

Q: Hello Simona and Ananda, and welcome. The vaccine has been used extensively since rollout began in March 2021. How would you say demand for the tool has been over the past two years?

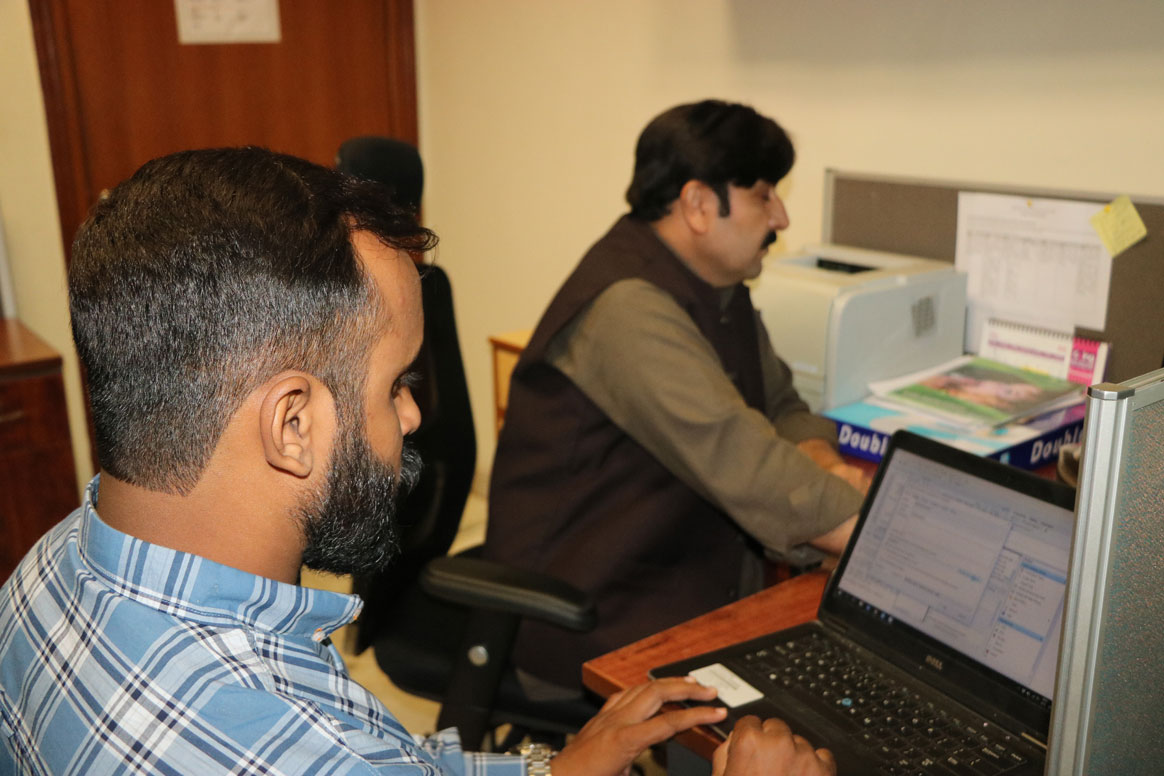

A: Simona – When nOPV2 was first made available in March 2021 following its Emergency Use Listing (EUL) authorization, we weren’t sure what demand would be like to be honest. The EUL was a new pathway for Public Health Emergencies of International Concern at that point—nOPV2 was the first vaccine that received one through WHO—and countries already had access to mOPV2, a proven vaccine that’s effective at stopping outbreaks. On top of that, use of nOPV2 came with an additional set of requirements countries had to meet due to its EUL status—they needed to show they were set up to monitor the vaccine’s performance and safety profile, as well as be ready to address any unexpected findings. But what we saw was high demand right from the outset. I think this was due in large part to our strong collaboration with the WHO and UNICEF regional offices even in advance of the EUL, where we worked together to clearly explain to countries what nOPV2 is, where it had the potential to add value, and what they would need to do in order to use it. By the time the vaccine was available, countries were already aware and able to make informed decisions with their National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups and National Regulatory Authorities on whether it was the right tool for them. Over time, we have seen confidence in the vaccine increase along with demand—last year over 94% of the type 2 vaccine used in outbreak response was nOPV2. I think the strong monitoring of the vaccine’s performance, safety and genetic stability has also really helped build trust in the vaccine. Today, we have used the vaccine in 28 countries, with an additional 13 countries having already met the requirements to use it in case of an outbreak.

Q: 600 million doses administered is a lot of vaccine. Is usage evenly distributed across the 28 countries? And how are we doing in terms of vaccine supply, given the demand?

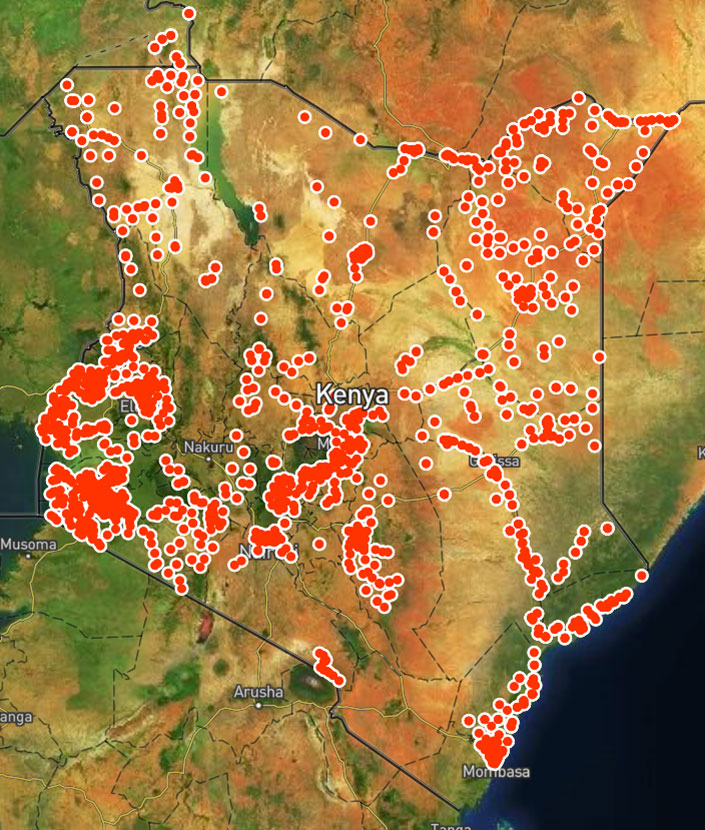

A: Simona – nOPV2 is not used in routine immunization programs, but only for outbreak response. Like all type 2 polio vaccines it is managed through a global stockpile. For nOPV2 this means that a country can’t just go and ‘order’ the vaccine—the only place it can be sourced from is the global stockpile. To access the vaccine, countries must not just meet the readiness requirements but also submit a risk assessment for the current outbreak, which needs to be approved before the WHO Director-General is asked to release nOPV2 for the response. This means that nOPV2 is distributed based on outbreak needs and risk assessments. While nOPV2 has been used in the European region, Eastern Mediterranean region, as well as the Southeast Asian region, over 95% of the vaccine used to date has been in Africa where there is the biggest burden of type 2 outbreaks. Even within Africa, use of the vaccine varies by country—countries where there is a high burden of type 2 outbreaks have used more vaccine. Nigeria alone accounts for over 60% of global nOPV2 administration.

Supply of nOPV2 continues to be something we monitor closely. We expect to have access to around 600-650 million doses of nOPV2 in 2023—which is more type 2 vaccine than we have ever used for outbreak response in a year. However, while we have a lot of vaccine available this year overall, we don’t have it all available now. So depending on when outbreak response is needed, we may have some months when we are short on supply—that’s something that needs to be consistently monitored and adjusted for.

The other challenging factor for supply is that we are seeing, with the increased confidence in nOPV2 being more genetically stable than Sabin mOPV2 and less likely to seed new outbreaks, that the scope of outbreak responses is increasing, leading to higher demand for the vaccine. We currently only have one global nOPV2 supplier, BioFarma in Indonesia, who are doing an extraordinary job on the manufacturing front. But there is a definite risk to consistent supply and work is underway to have a second manufacturer supplying nOPV2 in 2024.

Q: Let’s talk about effectiveness. Has the vaccine been successful in stopping outbreaks?

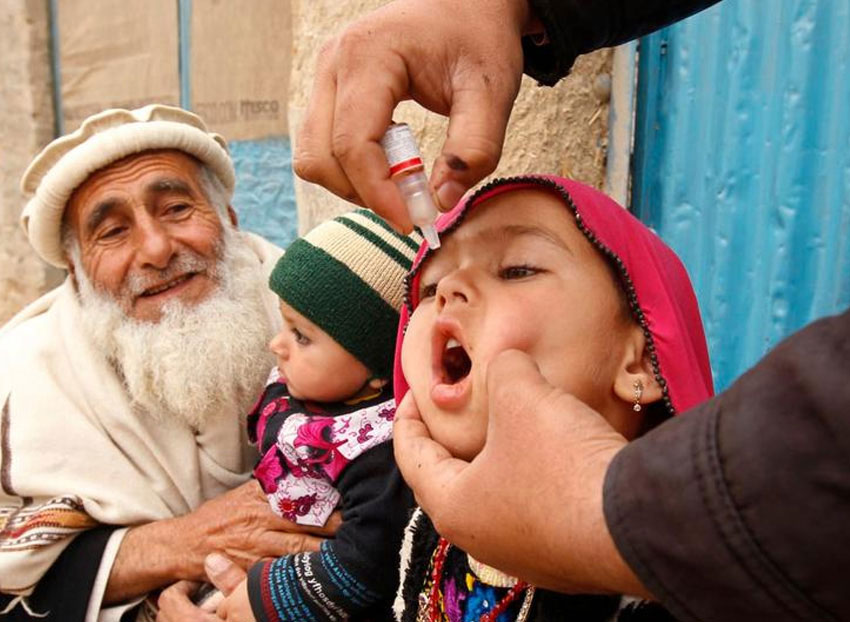

A: Ananda – Yes. More than two thirds of all countries that have used nOPV2 for outbreak response did not report continued transmission following two vaccination campaigns. In some areas with persistent transmission, we’ve seen interruption [of transmission] after a third round. There are, however, a few geographic settings where the virus persists despite multiple campaigns, and these are the areas where we need to focus more on reaching missed children with the vaccine, to stamp out the remaining reservoirs of transmission. Overall field effectiveness of nOPV2 in stopping paralytic outbreaks seems to be comparable with Sabin mOPV2, which is in line with clinical study findings. Most importantly, with lower risk of seeding new outbreaks compared to the Sabin mOPV2 experience as noted by field data so far, nOPV2 continues to demonstrate that it is an excellent tool to more sustainably stop outbreaks.

Q: What about safety? Are findings also in line with clinical studies?

A: Simona – Monitoring nOPV2’s safety has been one of our top priorities during the EUL period. We worked with the WHO pharmacovigilance team to set up an independent safety monitoring group to review the data and guide us in this regard. The Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety’s nOPV2 sub-committee meets every six months to review data on nOPV2’s field performance. Because there has been such large-scale use of nOPV2, it has allowed us to generate a lot of data on safety from field use. So far, the sub-committee has reviewed safety data from over 370 million doses of nOPV2 administered and has not identified any safety red flags or concerns, noting that despite enhanced monitoring, the rate of adverse events following immunization with nOPV2 remains lower than published rates for other OPVs.

Q: And coming back to enhanced genetic stability compared to mOPV2, which is the primary reason this vaccine was developed, tell us more on how nOPV2 is performing on that front.

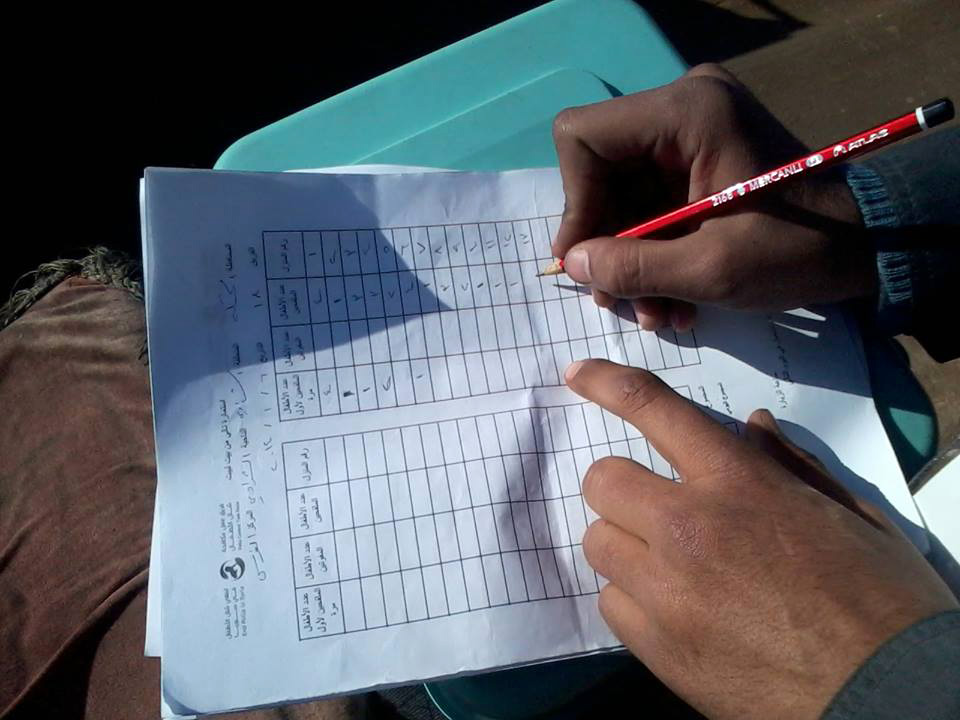

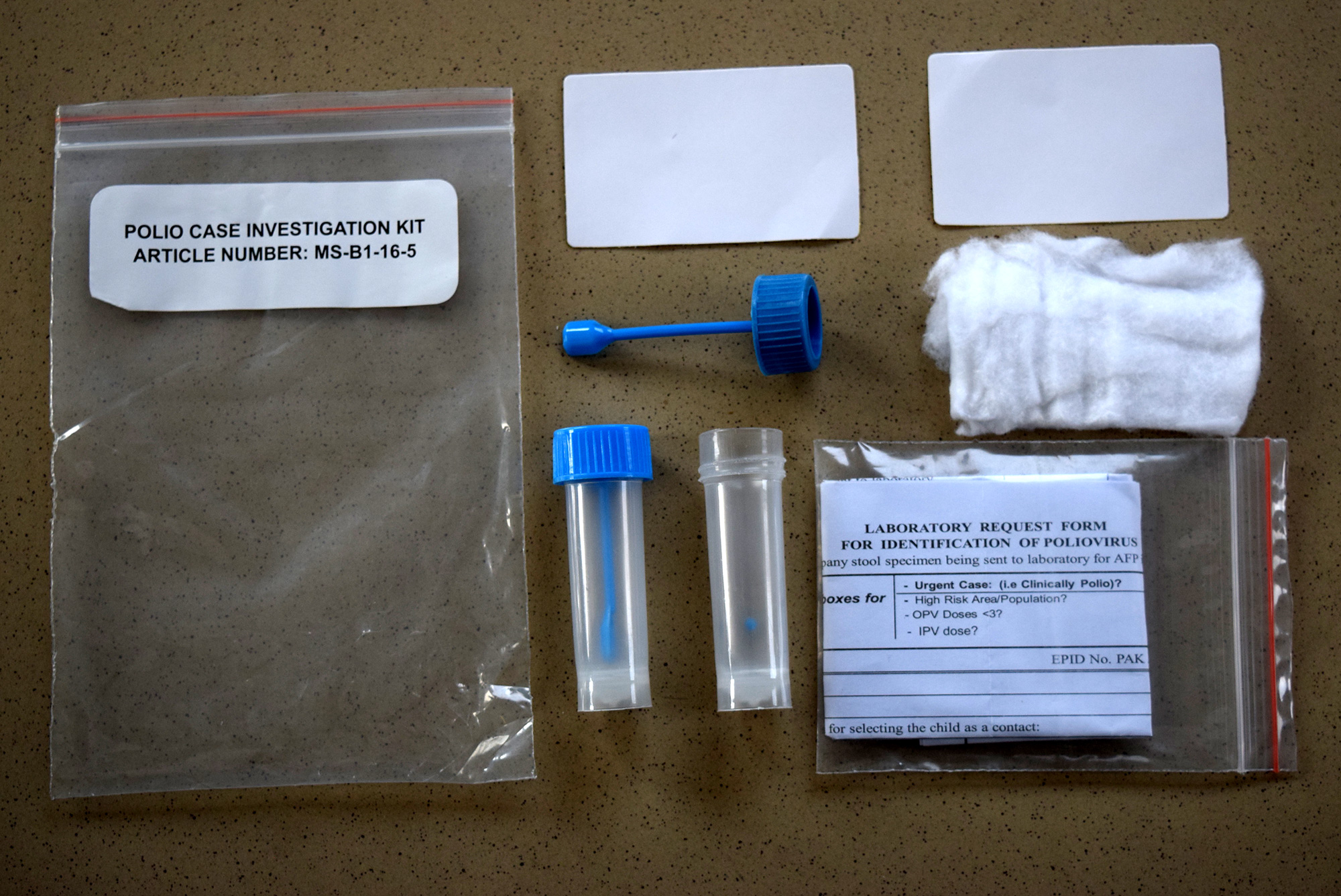

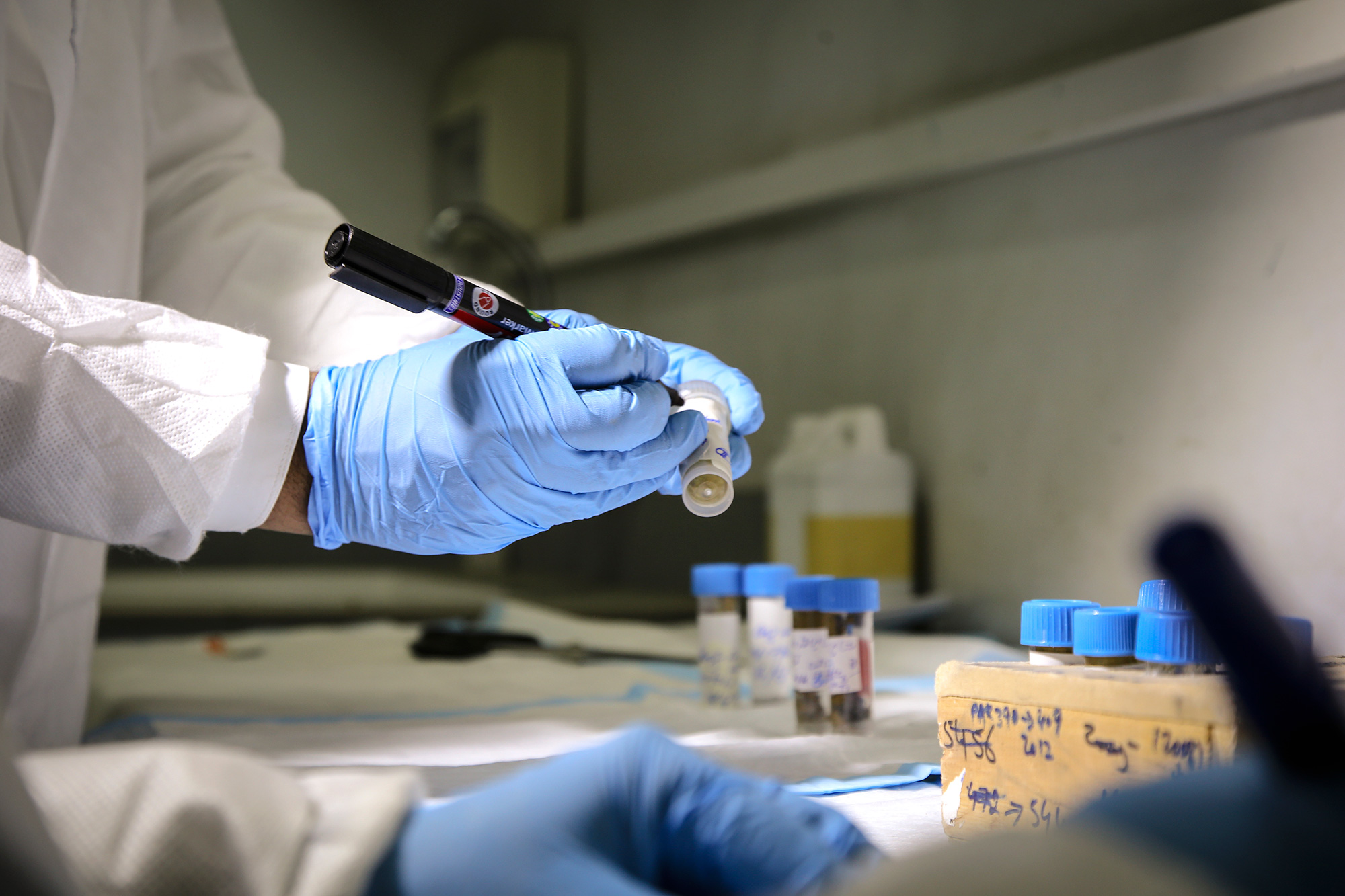

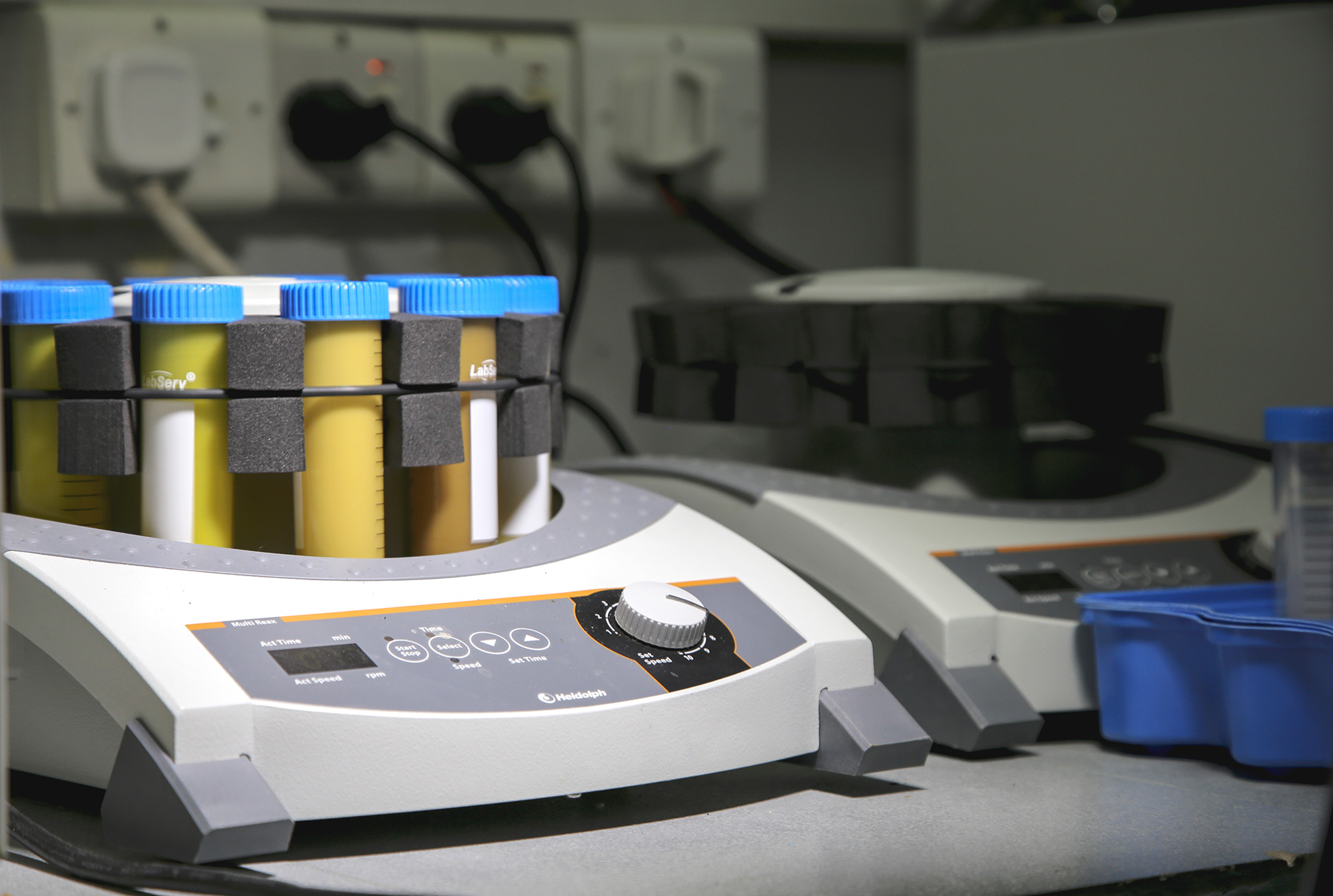

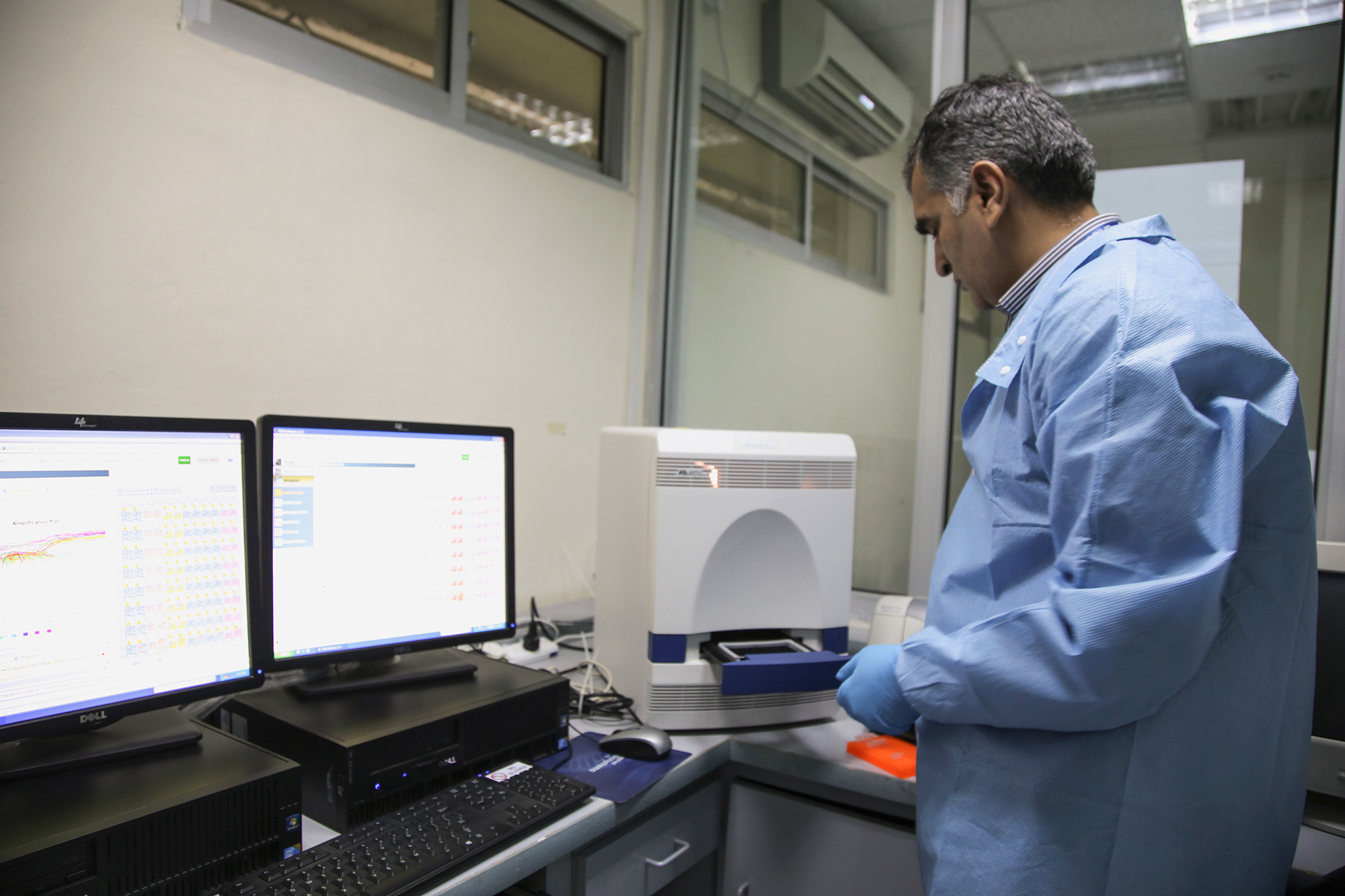

A: Ananda – An unprecedented level of effort has been put in place to monitor the genetic stability of the vaccine since rollout began, thanks to a dedicated group of experts led by US CDC and NIBSC UK and collaborators at the Global Polio Laboratory Network. Based on extensive analysis of whole genome sequencing data from isolates collected through sewage and clinical syndromic surveillance systems that are in place for polio, evidence supports nOPV2’s superior genetic stability compared to Sabin mOPV2, consistent with what was observed in pre-clinical and clinical studies.

I must clarify that significantly higher genetic stability and lower risk of reversion to neurovirulence compared to Sabin mOPV2 does not mean nOPV2 has no risk of reversion. Thanks to a sensitive surveillance system, a handful of such instances of reversion to neurovirulent variants have been picked up in settings of persistently poor immunization coverage.

We’ve seen, very recently, evidence of reversion of public health significance in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where two separate emergences of circulating variant poliovirus type 2 of nOPV2 origin have been detected, likely derived from double recombination events with human species C enteroviruses. Such recombination events and reversions resulted in seven paralytic cases in the DRC and neighboring Burundi.

In separate events, we also saw the detection of reverted and recombinant poliovirus variants of nOPV2 origin in two cases of paralytic polio in the Central African Republic in February 2023 and in an environmental sample collected in Uganda in February 2022. However, to date, circulation of these viruses in CAR and Uganda has not been established. These numbers are based on on-going assessment, and thus may change as GPEI continues the monitoring, laboratory work and field investigations.

With the much wider scale of nOPV2 use in areas of very limited background intestinal immunity for type 2 poliovirus, we may pick up more of these rare reversions going forward. It’s important to note, however, that overall trends of structural and functional changes [to the vaccine virus genome] of public health consequence remain dramatically lower with nOPV2 compared to prior experience with Sabin mOPV2. However, the program will continue to closely monitor the field-use data and interpret it with adequate nuance and contextualization.

Q: I suppose that campaign quality continues to be a key factor in reducing the risk of genetic reversion, then, even with nOPV2. Why is that?

A: Ananda: Enough children need to be reached enough times with vaccination efforts to stop virus circulation in areas with outbreaks. If children are missed, the virus causing the outbreaks will continue to circulate and spread. In addition, in such pockets of under- and un-vaccinated children who have sub-optimal intestinal immunity against poliovirus, the live attenuated or weakened strains of OPV – Sabin OPV and novel OPV included – can replicate and transmit long and sufficiently enough to acquire changes in their genetic structures, often through interactions (e.g. recombination events) with other enteroviruses in these settings to evolve into poliovirus variants that are structurally different from the vaccine strains, and that can potentially trigger new paralytic outbreaks. On the other hand, if OPV vaccination coverage is persistently high, meaning enough children are reached enough times, such rare risk of evolution into poliovirus variants of public health importance almost never arise.

Q: What needs to happen for nOPV2 to receive full licensure?

A: Ananda – This is already in process, thanks to the collaborative work of many partners, and continued guidance from the WHO prequalification (PQ) team and the Indonesian regulatory authority, BPOM. BioFarma is in the process of putting together the dossier for WHO Prequalification, that includes phase III study data that was led by PATH, data from other clinical studies such as one done in Bangladesh led by icddr,b in newborn infants, and additional information as required for this process. If this dossier is submitted by BioFarma by the end of March as per current targets, the expectation is to have a decision on WHO PQ and, therefore, full licensure of the vaccine before the end of 2023.

Q: What will happen to the key monitoring functions, for example, safety, genetic stability, etc.? Will these continue after PQ?

A: Simona – Like all vaccines, nOPV2 will continue to be monitored even after it is fully licensed, using the existing systems in countries, regions and at the global level. For example, countries will continue to implement acute flaccid paralysis and environmental surveillance, adverse events following immunization surveillance, and report any safety findings of concern to the Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety. GPEI will also continue to monitor the vaccine’s genetic stability through the Global Polio Laboratory Network.

Q: Last question: How is work on nOPV 1 and 3 progressing?

A: Ananda – Phase I studies with nOPV type 1 and nOPV type 3 – both in development to combat the two other types of variant polioviruses – have been completed in the United States, led by PATH. The plan is to launch into phase II studies in 2023, and also to complete a preliminary assessment of the feasibility of a multivalent nOPV formulation and its subsequent clinical development. Overall, we expect to have phase II study or target population data on these vaccines by 2025-2026, per current projections. Availability of these novel vaccine choices should enhance our probability of success to achieve and sustain eradication of all forms of polioviruses so that our children can thrive and prosper in a polio-free world.