Both were exceptionally talented researchers, so united in their desire to rid the world of polio that they inoculated themselves and their families with disabled versions of the virus. Yet the rivalry between Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin was intense, with Sabin once suggesting that Salk’s efforts could be achieved in a kitchen sink.

The source of their hostility was a disagreement about the best way to immunise people against polio. Salk believed the answer lay in a “killed” virus vaccine – where the virus particles had been chemically inactivated, so they could no longer replicate or cause disease. Sabin favoured using a “live” oral vaccine – one containing live, but weakened, virus particles that could replicate but couldn’t cause paralysis.

The incidence of polio has reduced by 99.9% and GPEI and its partners have achieved what many had assumed would be impossible: the eradication of polio from all but a handful of countries.

Salk’s inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) entered human trials and was approved first. But it was Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV) that became the global workhorse in polio eradication efforts and has been largely responsible for driving polio to the brink of extinction. However, polio isn’t gone, and the combination of COVID-19, ongoing conflict and political turmoil, has given polio the space it needed to fight back. Now, as polio eradication approaches its endgame, it is a combination of Salk’s and Sabin’s approaches that experts are hoping will prove to be humanity’s winning hand.

War on polio

Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, progress towards eradicating polio was proceeding at a remarkable rate. During the 1940s and ’50s, when polio outbreaks were a common scourge of the summer months, the disease killed or paralysed more than half a million people worldwide each year – mostly children. The introduction of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) and, later, live attenuated oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) led to a dramatic reduction in the incidence of polio in higher-income countries during the 1960s and ’70s.

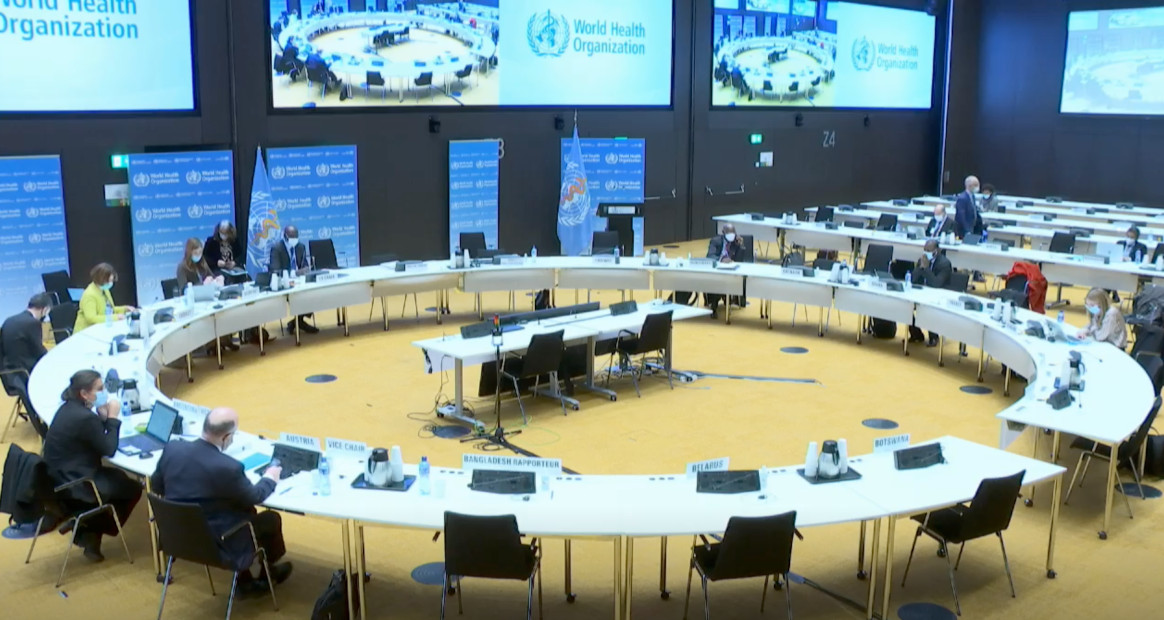

But it wasn’t until the 1980s that the battle against polio really commenced. At that time, community- and school-based surveys revealed that polio was the leading cause of paralysis in lower-income countries, with one in every 200 polio infections causing paralysis. In 1988, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution for the worldwide eradication of the disease, and a public-private partnership called the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was launched. Led by national governments, together with the World Health Organization (WHO), Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, UNICEF, and later joined by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, GPEI has made huge progress in protecting countries’ populations against polio through widespread OPV campaigns.

During this time, the incidence of polio has reduced by 99.9%, and GPEI and its partners have achieved what many had assumed would be impossible: the eradication of polio from all but a handful of countries.

Eradication endgame

In 2019, an independent commission of experts announced that wild poliovirus type 3 (WPV3) – one of three forms of the virus – had been eradicated worldwide. Type 2 poliovirus was declared eradicated in September 2015 – with the last virus detected in India in 1999 – leaving only Type 1 wild poliovirus at large in two endemic countries: Pakistan and Afghanistan.

In August 2020, when most people were preoccupied with fighting COVID-19, the WHO announced that all 47 countries in its Africa Region had been certified wild poliovirus-free following a long programme of vaccination and surveillance. Afghanistan and Pakistan were now the only places where wild poliovirus remained endemic, meaning it continued to circulate naturally in the environment.

“The past two years have demonstrated very clearly that there’s a very finite window to interrupt polio transmission and finish the job. Because if we do not eradicate polio, this virus will resurge globally.”

However, between 2019 and 2020, outbreaks of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) – a rare form of polio that occurs only in areas of low vaccination coverage – tripled, resulting in more than 1,100 children becoming paralysed. This year, cVDPVs have also been detected in the UK, US, and Israel, with some signs of limited community transmission. Wild poliovirus has also reappeared in south-east Africa, with a case detected in Malawi and seven cases in Mozambique.

“The new detections of polio this year in previously polio-free countries are a stark reminder that if we do not deliver our goal of ending polio everywhere, it may resurge globally,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. “We must remember the significant challenges we have overcome to get this far against polio, stay the course and finish the job once and for all.”

Disheartening as these setbacks are, they have provided a wake-up call to GPEI and its partners, and invigorated efforts to push polio eradication across the line. “I think the past two years have demonstrated very clearly that there’s a very finite window to interrupt polio transmission and finish the job,” said Aidan O’Leary, Director for Polio Eradication at the WHO. “Because if we do not eradicate polio, this virus will resurge globally.”

In 2020, GPEI launched a new roadmap to polio eradication, which set out two ambitious targets: firstly to permanently interrupt all poliovirus transmission in Pakistan and Afghanistan, stop transmission of cVDPV and prevent outbreaks in non-endemic countries by 2023. The second target is to certify the world free from polio – meaning no cases have been detected for three years – by 2026.

Achieving these goals will require a massive and concerted effort – with both OPV and IPV playing an integral role.

Polio vaccines

Polio is caused by a highly infectious virus that initially replicates in the nose or throat, before moving to the intestines and multiplying. From here, it can enter the bloodstream and invade the central nervous system, causing nerve damage and paralysis in around one in 200 people. Some survivors also develop post-polio syndrome, a disorder characterised by progressive muscle weakness and fatigue, which can severely impair their quality of life. However, around 70% of infected individuals are asymptomatic or have only mild symptoms, such as headache, fever and neck stiffness.

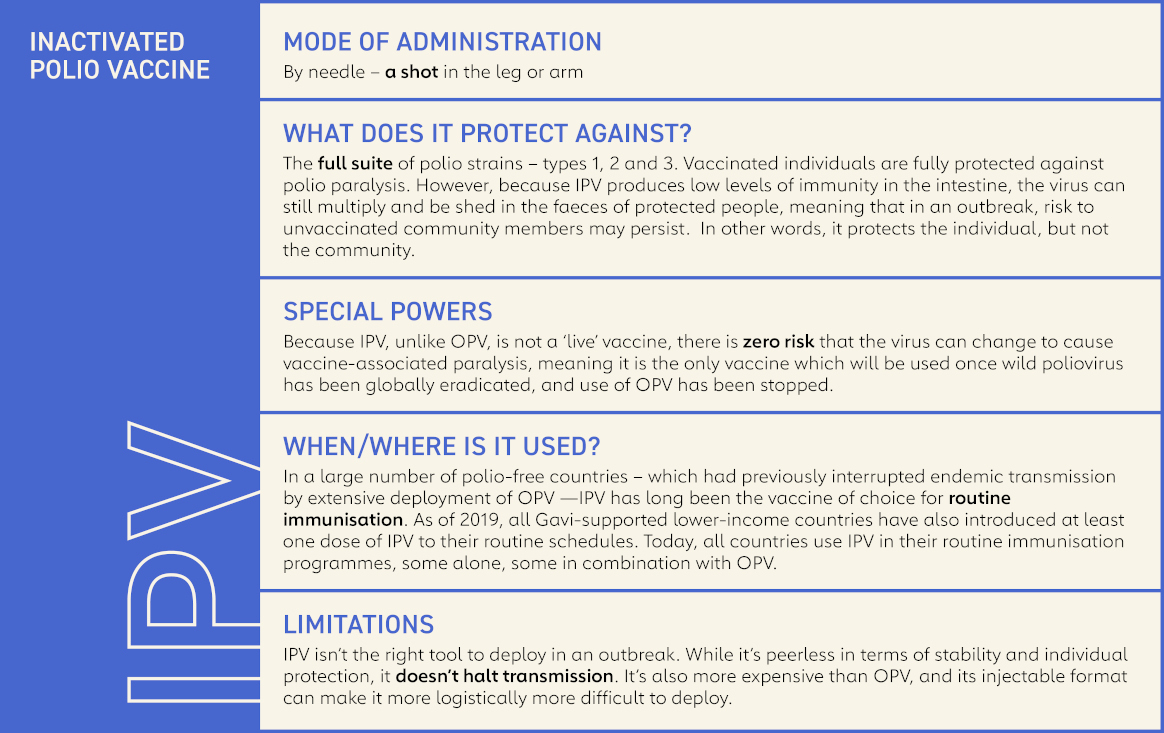

The development of vaccines against poliovirus has had a huge impact on its ability to circulate and cause disease, but OPV and IPV work in slightly different ways. IPV contains inactivated viral particles from all three poliovirus strains. Injected into the arm or leg, it is extremely effective at triggering antibodies against poliovirus in the blood, preventing the virus from travelling to the nerves and causing paralysis. However, it is less effective at triggering antibodies in the intestines, meaning vaccinated people can still become infected with poliovirus and transmit it to other people.

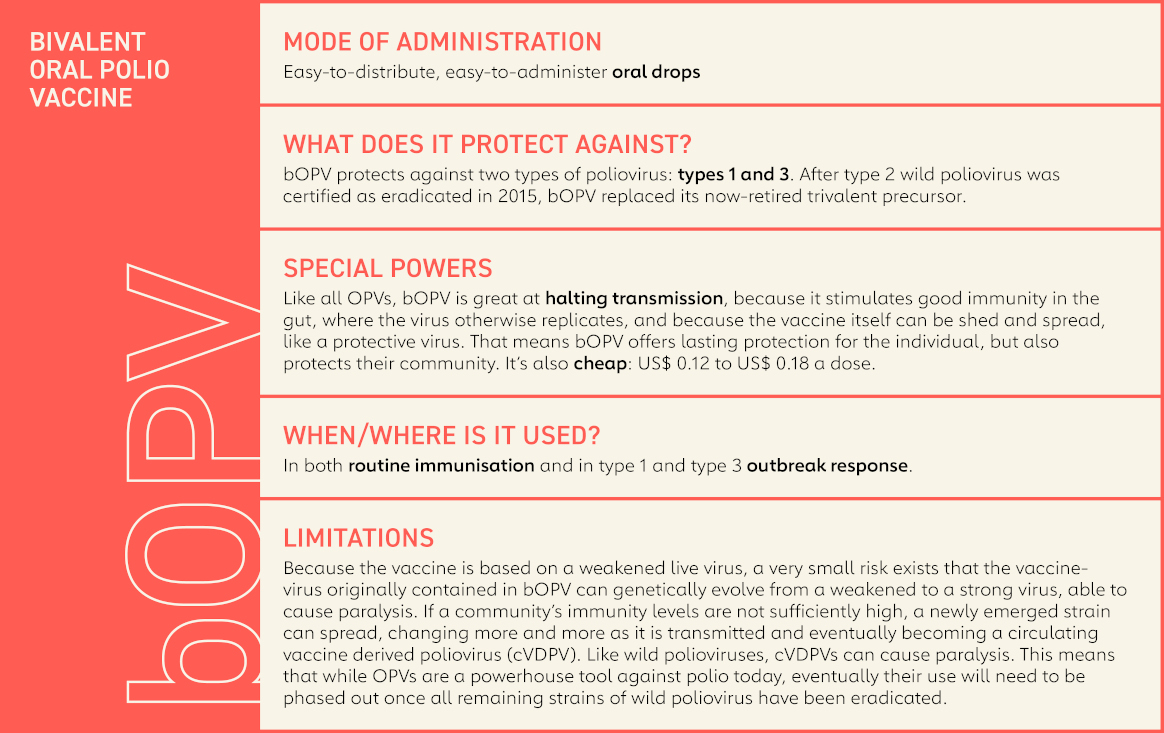

OPV, on the other hand, contains a mixture of poliovirus strains that have been weakened, meaning they can still replicate, but are not strong enough to cause paralysis. Because OPV is given via the mouth, it triggers the production of antibodies in both the intestines and the blood. This means that if a vaccinated person is exposed to poliovirus in the future, the virus won’t be able to replicate and infect other people.

This ability to block transmission, as well as being cheaper and easier to administer than IPV, led to the widespread adoption of OPV in most countries, and it has played a crucial role in eradicating wild poliovirus from all but a handful of places. However, because OPV contains weakened viruses that can replicate, some of them may be excreted by vaccinated individuals and transmitted to unvaccinated ones – particularly in areas with poor sanitation. This can be beneficial because exposure to weakened polioviruses helps to protect them against future infection.

However, it can also be problematic. In communities with high vaccine coverage, any onward transmission of vaccine-derived virus quickly fizzles out. But in those where fewer people have been vaccinated, weakened poliovirus may continue to circulate for months or years. Very rarely, these viruses can accumulate genetic changes that enable them to cause paralysis once more. If these strains continue to circulate, they can trigger outbreaks of what are called circulating vaccine-derived polio.

Under-immunised

Vaccine-derived polio is extremely rare, and only emerges in under-immunised populations. Between 2000 and 2021, more than 20 billion doses of OPV were given to nearly three billion children worldwide, and only 2,299 cases of cVDPV paralysis were registered during that period.

In the past decade, new types of OPV have been developed that reduce the risk of future cVDPVs emerging. Whereas earlier forms of OPV contained weakened forms of type 1, 2 and 3 polioviruses, since April 2016, all countries have switched to using bivalent OPV, which contains just types 1 and 3. This is helpful, because the weakened type 2 strain is responsible for nearly 90% of all cVDPVs.

“In all the areas where we face challenges, it’s due to a combination of issues around inaccessibility and security, non-functioning health systems, and communities that have become marginalised from the state, for a whole variety of reasons.”

Even so, vaccine-derived polio has emerged as a key challenge in the final stage of polio eradication. Three geographical locations, in particular, currently account for more than 90% of all global cases of cVDPV caused by the type 2 strain: northern Yemen, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and northern Nigeria. Ongoing conflict in south central Somalia is another concern.

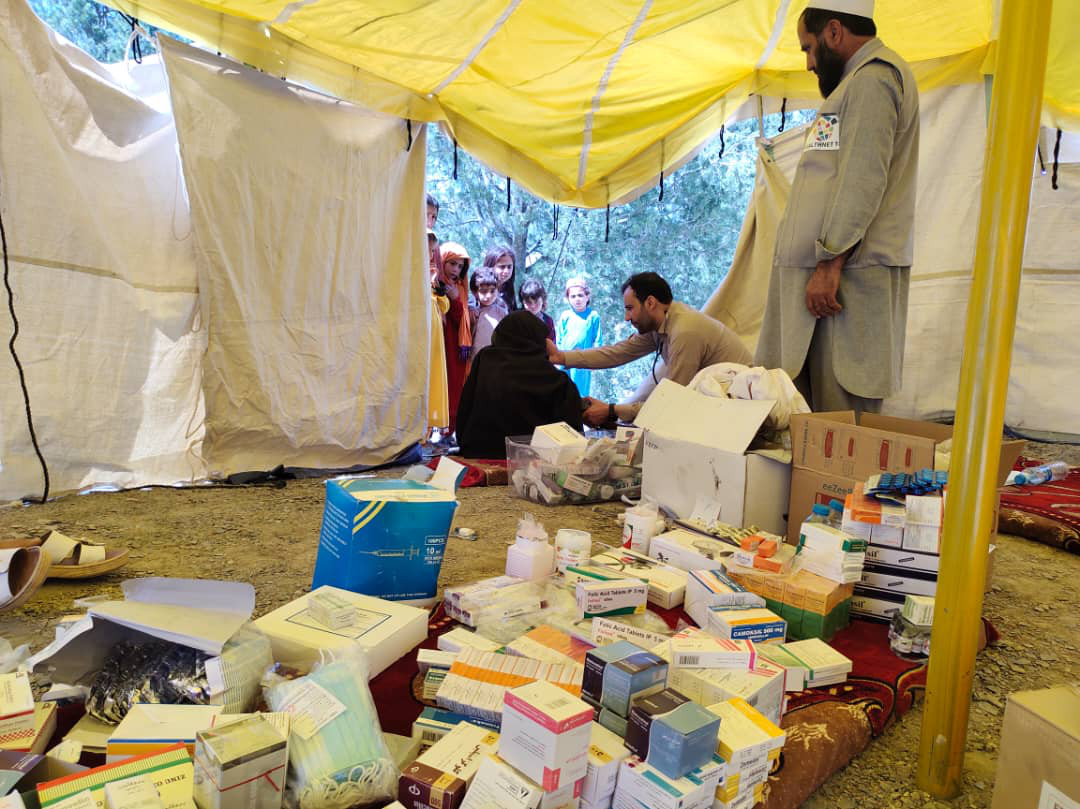

“In all the areas where we face challenges, it’s due to a combination of issues around inaccessibility and security, non-functioning health systems, and communities that have become marginalised from the state, for a whole variety of reasons,” said O’Leary.

The situation in Yemen is particularly worrying, because of ongoing restrictions on childhood vaccination imposed by the Houthi administration in Sanaa, Yemen’s largest city. “We understand that a lifting of these restrictions may be imminent, but a delay of more than 12 months has allowed the virus to continue to spread in a situation where the essential immunisation system is either non-existent, or very poorly performing. And it has wreaked havoc with more than 200 children being paralysed over the course of this period,” O’Leary said.

These pockets of cVDPV are bad enough, but international travel also means that infections can be seeded elsewhere – which is thought to explain recent detections of cVDPV in London, New York and Israel. The good news is that such outbreaks can be stopped using the same tactics that have so successfully stamped out wild poliovirus – strengthening polio surveillance and ensuring high vaccination coverage.

Race against the clock

In an outbreak scenario, time is of the essence, making OPV the vaccine of choice. “The key with OPV is that it’s safe, effective, cheap and very easy to use,” said O’Leary. “Particularly the children that we’re most concerned about, which is infants under the age of one or two, it is not an easy task to bring them – sometimes very extensive distances – to receive an injectable vaccine in a clinic. So, we flip it, and bring the vaccine directly to households to make immunisation as simple and straightforward as possible, while maximising the coverage that can be achieved.”

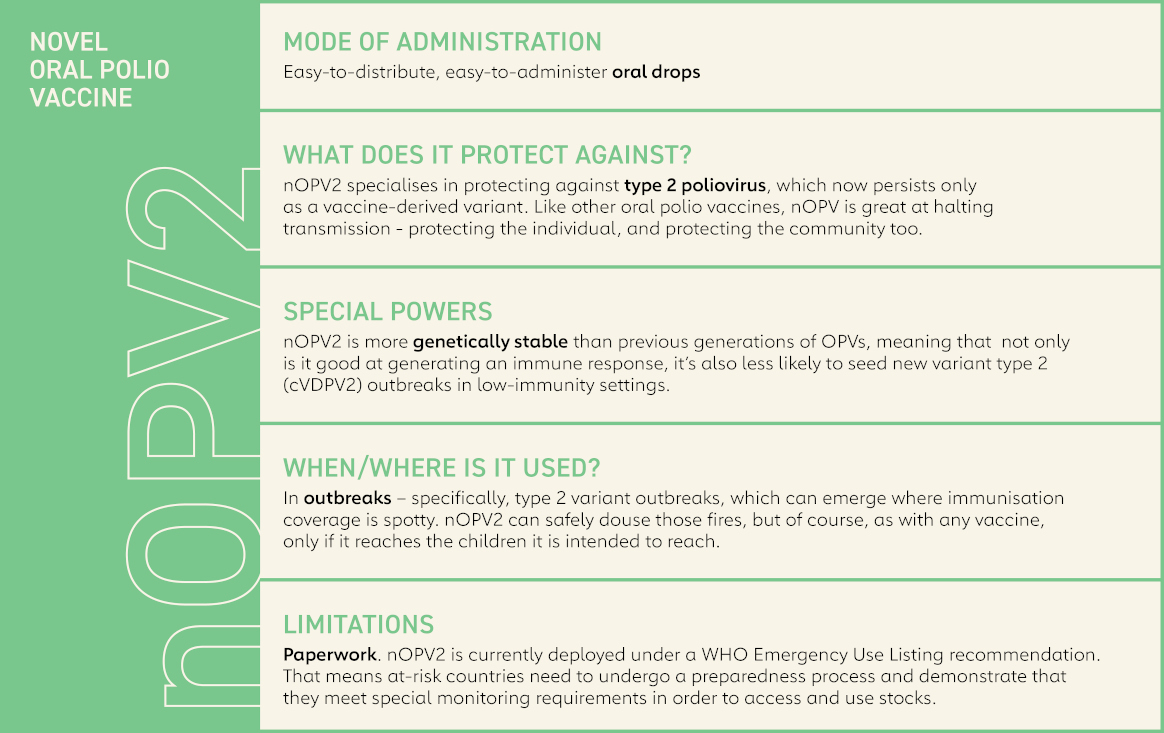

The risk of new cVDPVs emerging during these emergency campaigns should be further reduced through the recent introduction of another new OPV, called type 2 novel oral polio vaccine (nOPV2), which is specifically designed to extinguish cVDPV2 outbreaks in a more sustainable way. Like earlier OPVs, it contains weakened type 2 polioviruses, but they have been further modified to make them more stable, meaning they are significantly less likely to revert into a threatening form.

To eliminate the primary risk of emergence of all types of vaccine-derived polio cases, the Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic Plan (PEESP) called for the phased removal of the current Sabin-strain oral polio vaccine (OPV) – a critical and necessary step towards polio eradication. It’s important to clarify that the risk is not associated with the vaccine itself but rather low vaccination coverage. If a population is fully immunised, they will be protected against both vaccine-derived and wild polioviruses.

Endgame strategy

Ultimately though, the plan is to phase out OPV altogether. The problem lies not with the vaccine itself, but rather low vaccination coverage and the possibility of new cVDPVs emerging.

⌈If OPV has been the artillery in the war against polio, then IPV provides the cavalry needed to finish the job.⌉

Enter IPV. With polio eradicated from most continents and countries, the key to keeping it that way is maintaining high levels of population immunity – not just in adults and children who have previously been vaccinated against polio, but in children being born today and in the coming years – through routine childhood immunisation with IPV.

If OPV has been the artillery in the war against polio, then IPV provides the cavalry needed to finish the job, said O’Leary: “It needs to be significantly bolstered up everywhere, to sustain the gains that have been made. That ultimately means strengthening essential immunisation systems across the board.”

Until the COVID-19 pandemic hit, these efforts had been proceeding at pace. Nepal became the first country to introduce routine immunisation with IPV with Gavi support in 2014. Within five years all Gavi-supported countries had successfully completed their introductions – collectively immunising more than 112 million children.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has set back the delivery of all routine childhood immunisations. “The big area of concern has been the jump from just under 19 million children who were categorised as zero-dose – meaning they are not receiving a single dose of routine vaccines – to more than 25 million,” said O’ Leary.

The final mile

Contained within GPEI’s new roadmap, The Polio Eradication Strategy 2022–2026, is a commitment to reverse this trend by rapidly rebuilding coverage rates in those areas where shortfalls are being recorded.

Whether GPEI and its partners can really make up enough ground to stop the transmission of wild poliovirus globally by the end of 2023, remains to be seen, but their resolve and commitment to go the final mile is unwavering.

“It’s not the first time such targets have been offered. But what’s different this time around is that, in addition to mass vaccination campaigns, the initiative’s new strategy will be intensely focused on finding targeted ways to reach missed communities and take advantage of opportunities to become more integrated with other essential services.” said Seth Berkley, Gavi’s CEO. “In these communities, children are not just consistently missing out on protection from polio, they are also missing out on a whole range of other critical health interventions and other vaccines.”

If the eradication of polio is successful, it would only be the second human disease, after smallpox, to have been scrubbed from the face of Earth. “Notwithstanding all the doom and gloom with the COVID-19 pandemic and other challenges, it really is feasible – if we remain very focused on that goal,” said O’Leary. “And it absolutely requires both types of vaccine.”

Re-posted with permission from GAVI.