Afghanistan is closer than ever to eradicating polio. Through this photo essay, discover 10 innovative approaches that are bringing Afghanistan closer to ending polio, for good.

During vaccination campaigns, healthcare workers knock on every door around the country to deliver polio vaccines. But when a child is not at home to receive the vaccine it can mean that they are left vulnerable to the poliovirus. To address this problem, vaccinators now return to any household where a child was missed to give them a second shot at protection a few days after the campaign has taken place. In this photo, Zahra marks the pinky finger of a child after vaccinating her during a picnic in a women’s garden in Kabul on a Friday re-visit.

Even in areas where conflict makes it challenging, a network of people across Afghanistan are on the alert for the poliovirus. Over 28 000 people including volunteers, health workers, teachers, religious leaders and traditional healers look for signs of polio, such as floppy or weakened limbs and a fever. This network of committed individuals has grown nearly 20% over the past year.

As well as looking for the symptoms of polio, Afghanistan continues to step up the hunt for the poliovirus in the environment. Currently, water samples are taken from 20 sites in nine provinces to be tested in the laboratory. Four new environmental sampling sites have been established in 2017 and sampling frequency has been doubled in high-risk areas in the south. This helps determine how the virus is spreading around the country and to find it even before it can cause paralysis so that campaigns can be held to stop it.

Afghanistan has deployed 42 vaccination teams at 18 border crossing points with Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran. Every month, these teams vaccinate on average more than 105 000 children under 10 years of age crossing the border. In 2016 alone, the teams vaccinated over a million children against polio.

Since January, over 42 000 children returning to Afghanistan from Pakistan have received the oral polio vaccine and 18 000 children have been vaccinated with the inactivated polio vaccine at UNHCR and IOM reception sites near the border. In addition to vaccination, teams collect information on where the families are headed to ensure that they receive the follow up doses they need to ensure that they are fully protected.

Permanent transit teams help to reach children in inaccessible areas with vaccines. Currently 387 permanent transit teams, up from 163 in 2016, are stationed in strategically selected locations such as informal border crossings, busy transport hubs, major market places, health facilities and entry/exit points of inaccessible areas. The teams vaccinated over 10 million children in 2016.

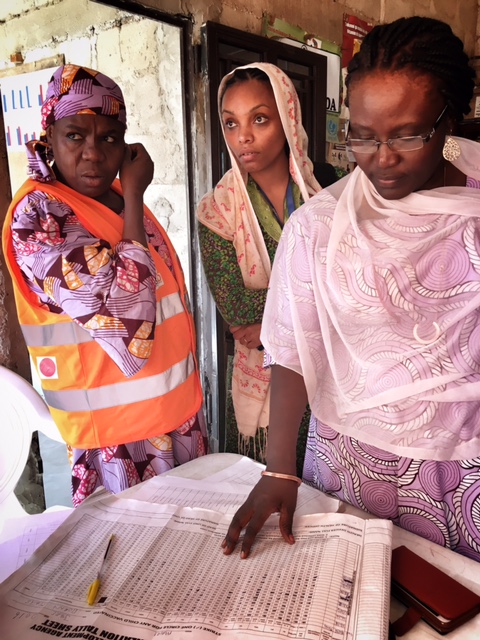

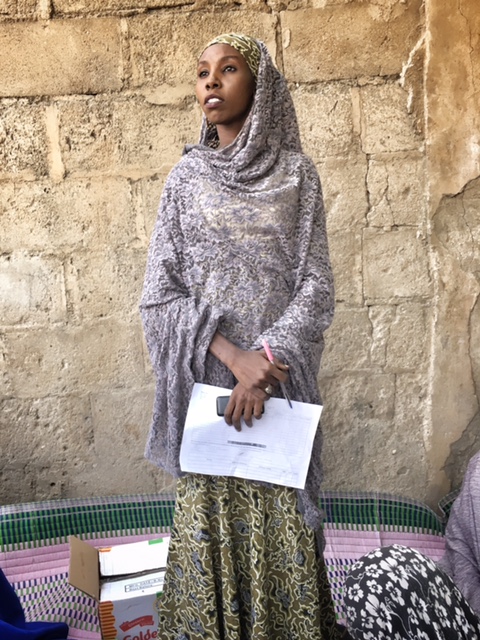

The success of polio eradication depends on the single moment that a healthcare worker knocks on the door of a child who needs the vaccine. All polio frontline workers, over 65 000 Afghan men and women, have been given training to help them engage families and vaccinate every last child. The polio programme has also been working to employ more women; the countrywide proportion of female vaccinators is 12%; however, in the urban areas the proportion of female polio workers has already reached 45%. This can help reach more children in more traditional areas of the country.

Comprehensive microplans are at the core of successful vaccination campaigns, mapping where communities and households are located in each area and how many children live there. Before every campaign, each local microplan is updated using new technology and local knowledge. This process results in finding previously unreached villages and children as well as in streamlining workloads of vaccination teams, supervisors and district coordinators.

Special strategies are in place across the country targeting nomadic groups based in Afghanistan as well as nomads who enter Afghanistan from Pakistan and move widely in the country before returning to Pakistan. Their routes, seasonality and places of settlements are known and the dates of special campaigns targeting the children of nomadic groups are adjusted accordingly. Special Permanent Transit Teams are deployed along the major movement routes in the Southern and Western regions, and nomadic settlements are included in supplementary immunization activity microplans across the country.

Religious leaders have become increasingly involved in polio eradication efforts in Afghanistan in the last years, spreading messages about the benefits of polio vaccines during Friday sermons and convincing caregivers in their communities to vaccinate children. So called “mobile mullahs” visit refusal families to talk about Islam’s support to vaccines.

The virus moves between Afghanistan and Pakistan unchecked by the border, meaning that the countries need to work together as one unit to stop it. The polio programmes in both countries have intensified coordination, with more regular communication and information sharing about population movements. Vaccination campaigns are held at the same time and if any case of acute flaccid paralysis is found, both countries are informed so that efforts can be scaled up in that area.