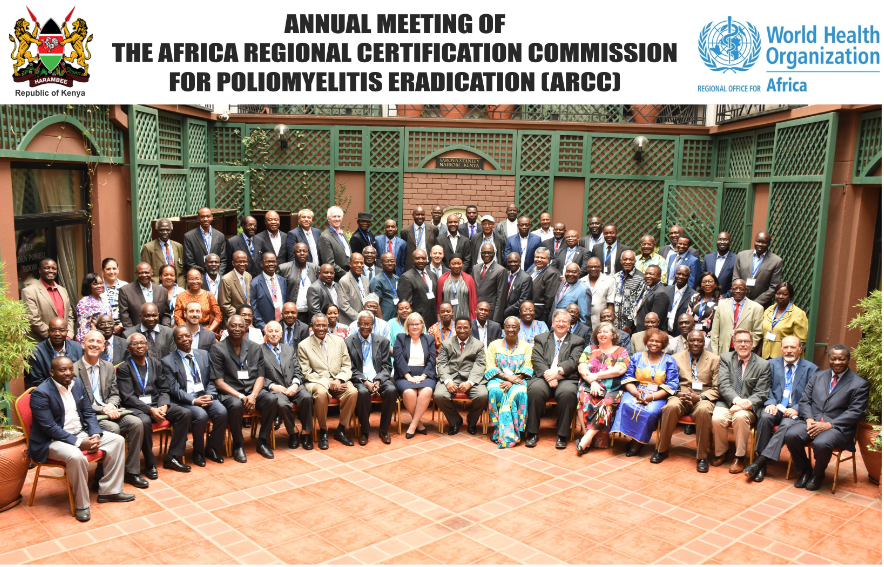

From the 27 – 29 November, the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) met in Nairobi to review the outbreak response in Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya, and preparedness measures in Yemen, Uganda, Tanzania, Sudan, South Sudan and Djibouti in case of international spread.

Jean-Marc Olivé, Chairman of the TAG, spoke to WHO about the recommendations made to address the challenges faced by countries, his hopes for eradication and his life in the programme.

What are the main challenges faced by the countries of the Horn of Africa in the drive to stop the outbreaks?

The major challenges have been the same for a long time – like, the issue of inaccessibility due to conflict and humanitarian crises. If we cannot access populations then it is very difficult to cover them properly during vaccination campaigns and so it is hard to stop poliovirus transmission. This is not a programme-related issue, it is a political one. Until we have access, it will be very difficult to make it.

I have said it before and I will say it again: access is success.

I think the second challenge is – and this is one of the reasons why we still have the transmission of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus in the Horn of Africa – is persistently low vaccination coverage. There are still remote areas, rural areas, heavily populated urban areas where routine immunization has really never been able to offer the same services and coverage as in more accessible areas with fewer challenges.

Since last TAG meeting in the Horn of Africa, what progress have you seen?

I have seen the capacity really building up in the Horn of Africa. The biggest shift is that we now have collected a lot of data about surveillance, about immunization coverage, vaccination campaigns, communications, and also data by the type of population we are reaching and not reaching. What is missing now, and what was the focus of this TAG, is to use this data to monitor progress and orient the programme toward those difficult areas. We have to use the data to tell us a story about what is happening and what to do next.

What were the most important recommendations made by the TAG this time around?

I think the most important is to follow the plan that has been set up for the three outbreak countries to interrupt transmission. Secondly, the countries that have not been yet infected by the virus should have a preparedness plan to ensure that if there are any problems they can move swiftly into action.

The Horn of Africa has seen several outbreaks in the past. What must be done to break the pattern and keep the region polio-free once and for all?

They have identified the problems. They just have to implement the solutions! We need to be sharing and analysing knowledge, information, and building capacity at the local level to ensure that we are on the right track to success.

I say to all the countries, go to the areas where you know you have problems and engage local communities and health authorities. Most of the issues can only be addressed at local levels by local people who understand the situation. Help them to do that, and monitor progress.

This is your thirteenth TAG; what have you learned about the process of international review?

First, you have to work as one team in support of National Teams, all agencies together. There cannot be any agency that claims, “This is us, we are doing that, this is WHO, this is UNICEF…”; this is the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, working together with all committed partners, using the competencies that each of them has. If you don’t address issues comprehensively as one, effective interventions are much more difficult to implement.

How long have you worked on polio eradication? What lessons have you learnt from this experience?

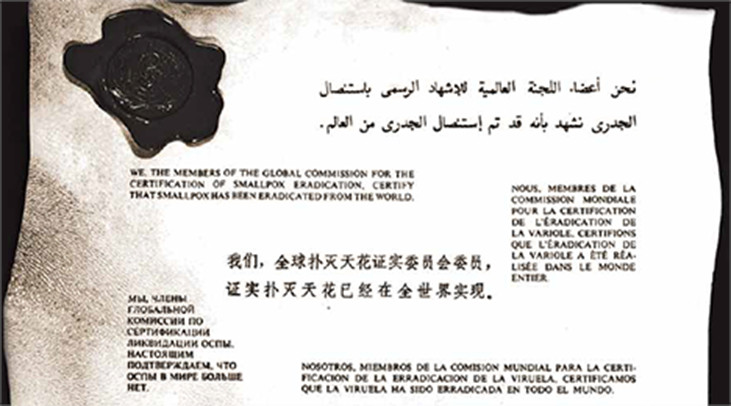

I was involved in the eradication of polio in the Americas. We started in 1985. We did it from A to Z in 9 years. We had very good leadership, commitment from the Government and partners, clear guidelines, very strong monitoring, and solid and reactive support to the field. Then we moved on into measles elimination with the same engagement – and the same results.

Because I have seen it happen, I know it is feasible. I think this is what keeps me so motivated. Polio eradication is a fantastic initiative. If we focus on weak and problematic areas within countries, if Governments and Partners continue to be engaged, we will make it. It’s going to be tough, mainly because of inaccessibility.

Is there anything else you want to add?

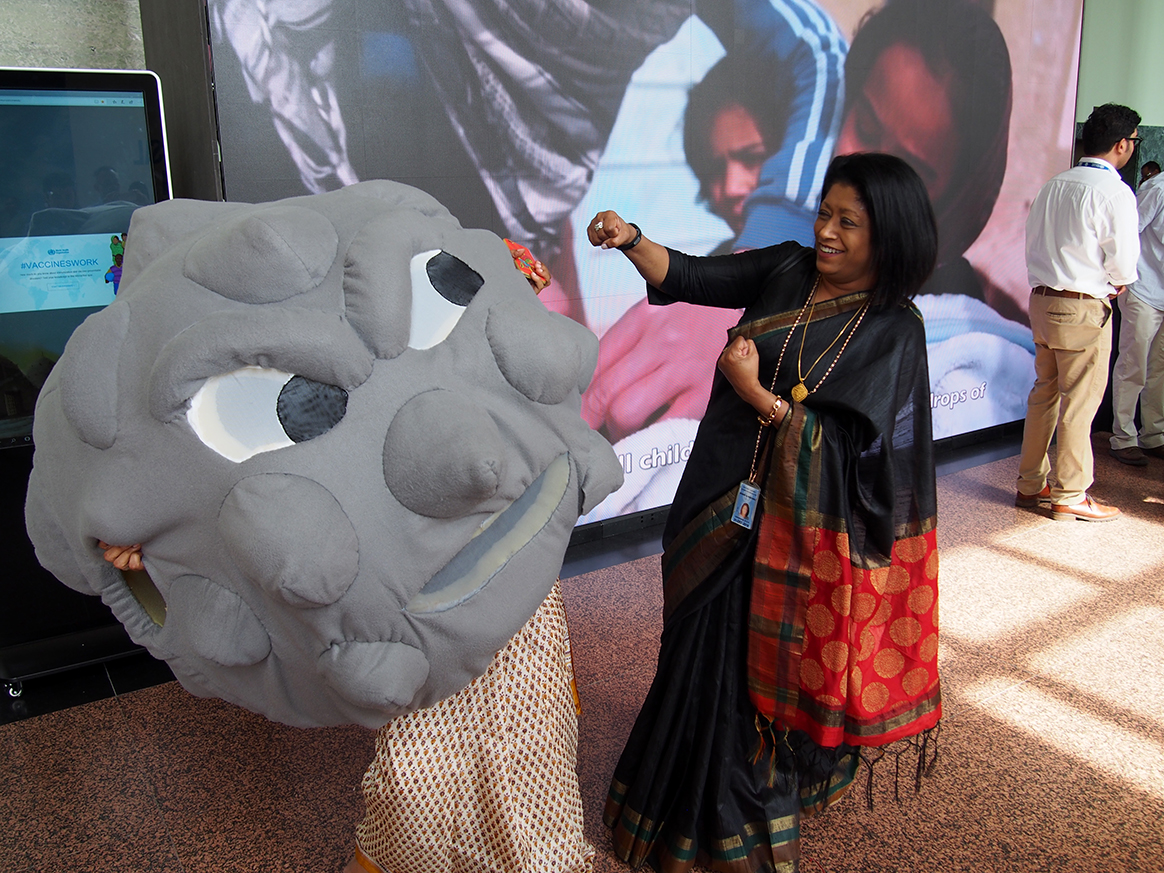

The people working in this programme, particularly local people working in the countries are amazing. They are the basis of any future public health intervention. In Pakistan and Afghanistan, woman are more and more playing an important role. This is an incredible advancement and an incredible contribution that was previously thought to be impossible.

But nothing is impossible – you just push, go slowly and constructively you will manage to gain ground over the virus.