WHO/H. Shukla

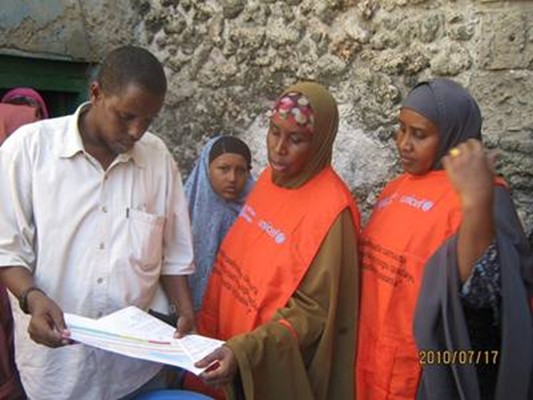

Vaccinators are carefully selected by the Community District Field Assistants (DFA). Many of these vaccinators are females from local communities who have been trained on polio vaccination. They play a key role as they walk from door to door, talking to families, giving vaccine – all to protect children against polio.

Vaccinators work long hours, starting at dusk and continuing through the evening only to break briefly for lunch. They vaccinate around 100 children each day and often walk many kilometers to reach pastoralist, nomadic and migrant populations. Vaccinators’ days can be unpredictable: if a security analysis identifies a window of accessibility in a previously inaccessible area, locally recruited volunteers will quickly go in to deliver additional doses of oral vaccines.

In Somalia, there are a number of challenges, starting with insecurity. In the South and Central zones, more than 35 districts are still partially or completely inaccessible due to insecurity.

Even in secure regions, implementing successful campaigns is difficult because more than half of the population lives in remote areas, and many communities are nomadic, traveling across Somalia and into Kenya and Ethiopia. We have set up 300 transit vaccination points across the country to vaccinate these people, but it remains difficult.

Another challenge is maintaining a cold chain system: with a lack of infrastructure in many parts of the country, vaccinators must use frozen ice packs to keep vaccines cold, which can be difficult when traveling across vast rural areas.

In general, people want vaccine. The Ministry of Health uses radio broadcasting to educate the community on vaccines and to announce polio campaigns, which is very effective because Somalia relies on the radio to obtain information. What’s more, vaccinators tend to come from the community they are working in, which helps build trust and vaccine acceptance.

Vaccinators are carefully selected by the Community District Field Assistants (DFA). Many of these vaccinators are females from local communities who have been trained on polio vaccination. They play a key role as they walk from door to door, talking to families, giving vaccine – all to protect children against polio.

Vaccinators work long hours, starting at dusk and continuing through the evening only to break briefly for lunch. They vaccinate around 100 children each day and often walk many kilometers to reach pastoralist, nomadic and migrant populations. Vaccinators’ days can be unpredictable: if a security analysis identifies a window of accessibility in a previously inaccessible area, locally recruited volunteers will quickly go in to deliver additional doses of oral vaccines.

In Somalia, there are a number of challenges, starting with insecurity. In the South and Central zones, more than 35 districts are still partially or completely inaccessible due to insecurity.

Even in secure regions, implementing successful campaigns is difficult because more than half of the population lives in remote areas, and many communities are nomadic, traveling across Somalia and into Kenya and Ethiopia. We have set up 300 transit vaccination points across the country to vaccinate these people, but it remains difficult.

Another challenge is maintaining a cold chain system: with a lack of infrastructure in many parts of the country, vaccinators must use frozen ice packs to keep vaccines cold, which can be difficult when traveling across vast rural areas.

In general, people want vaccine. The Ministry of Health uses radio broadcasting to educate the community on vaccines and to announce polio campaigns, which is very effective because Somalia relies on the radio to obtain information. What’s more, vaccinators tend to come from the community they are working in, which helps build trust and vaccine acceptance.