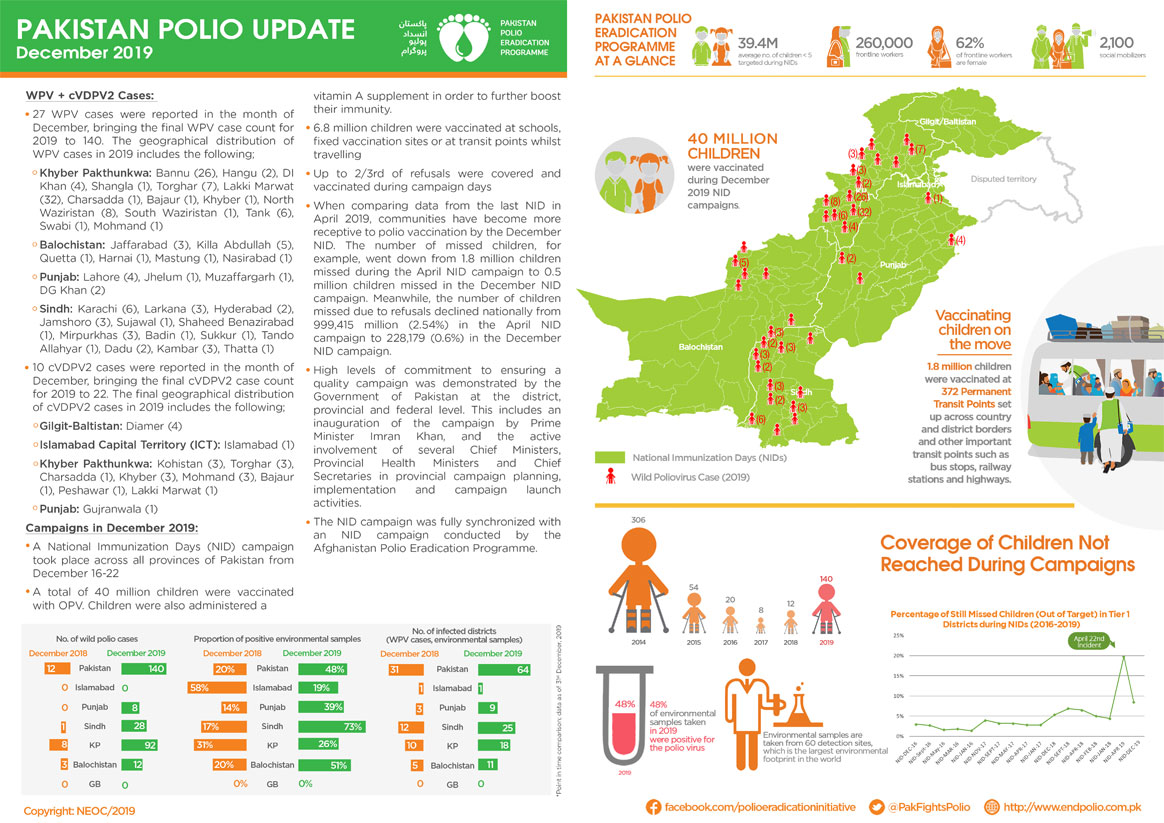

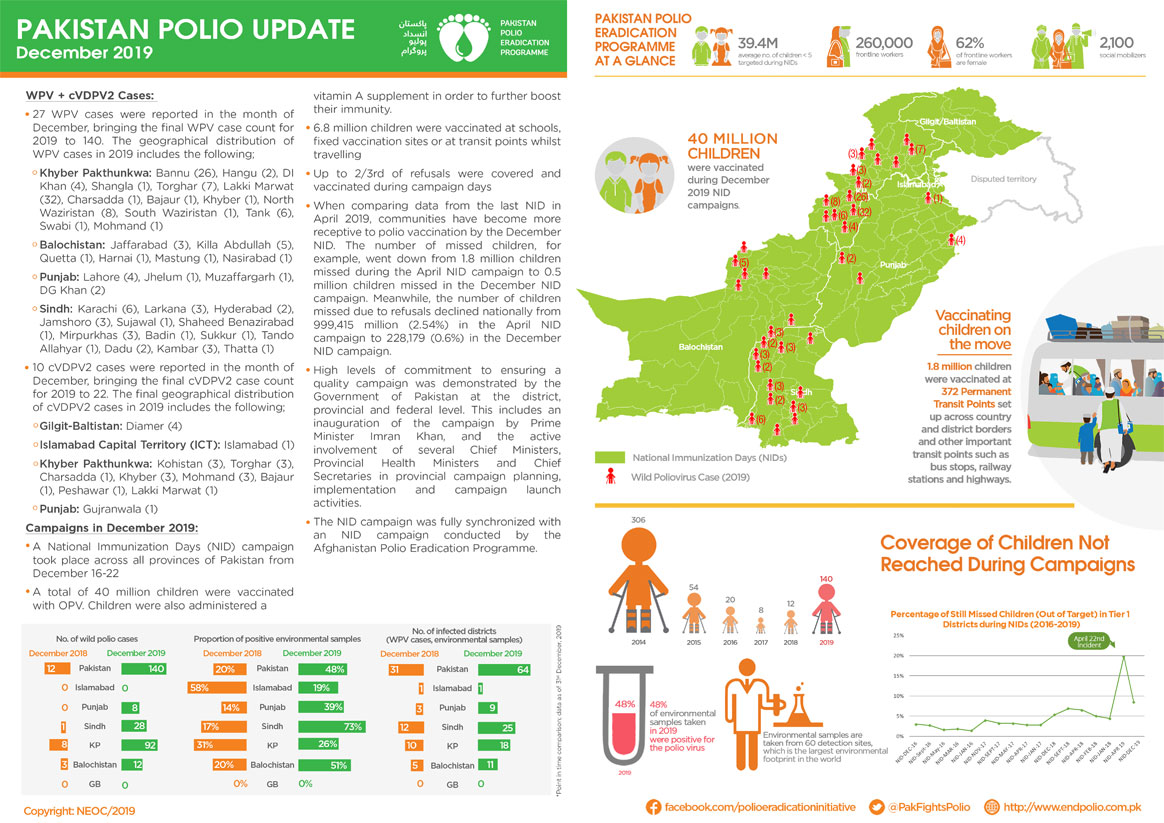

In December

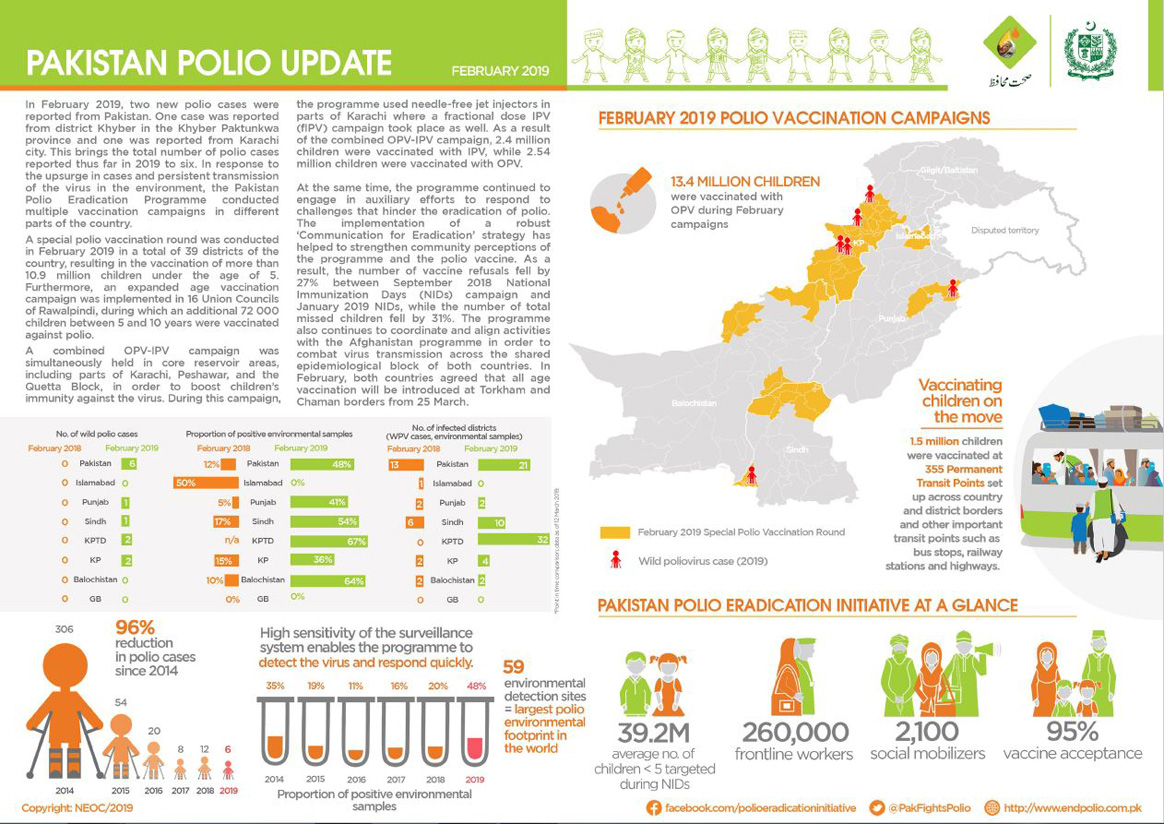

- 40 million children were vaccinated during the December NID Campaigns.

- 1.8 million children were vaccinated at 372 Permanent Transit Points.

In December

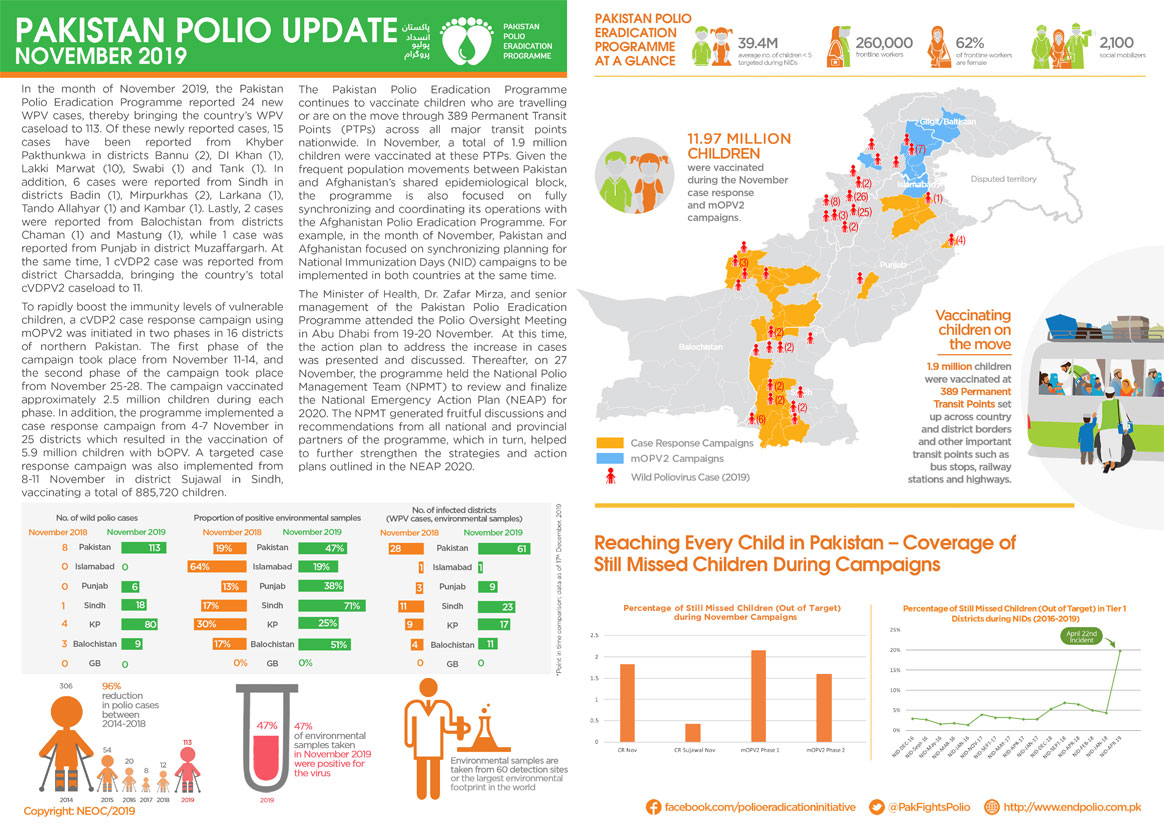

In November

In Karachi’s Gadap Town, many families lack basic health and municipal services. To fill the gap, the Polio Emergency Operations Centre in Pakistan’s Sindh province has recently renovated an abandoned hospital to create an Emergency Response Unit (ERU). The unit provides polio vaccination to communities alongside PolioPlus activities to improve overall health. The unit was built with the support of Rotary International, WHO, UNICEF and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Click through the gallery to see how the Gadap Emergency Response Unit has changed health delivery:

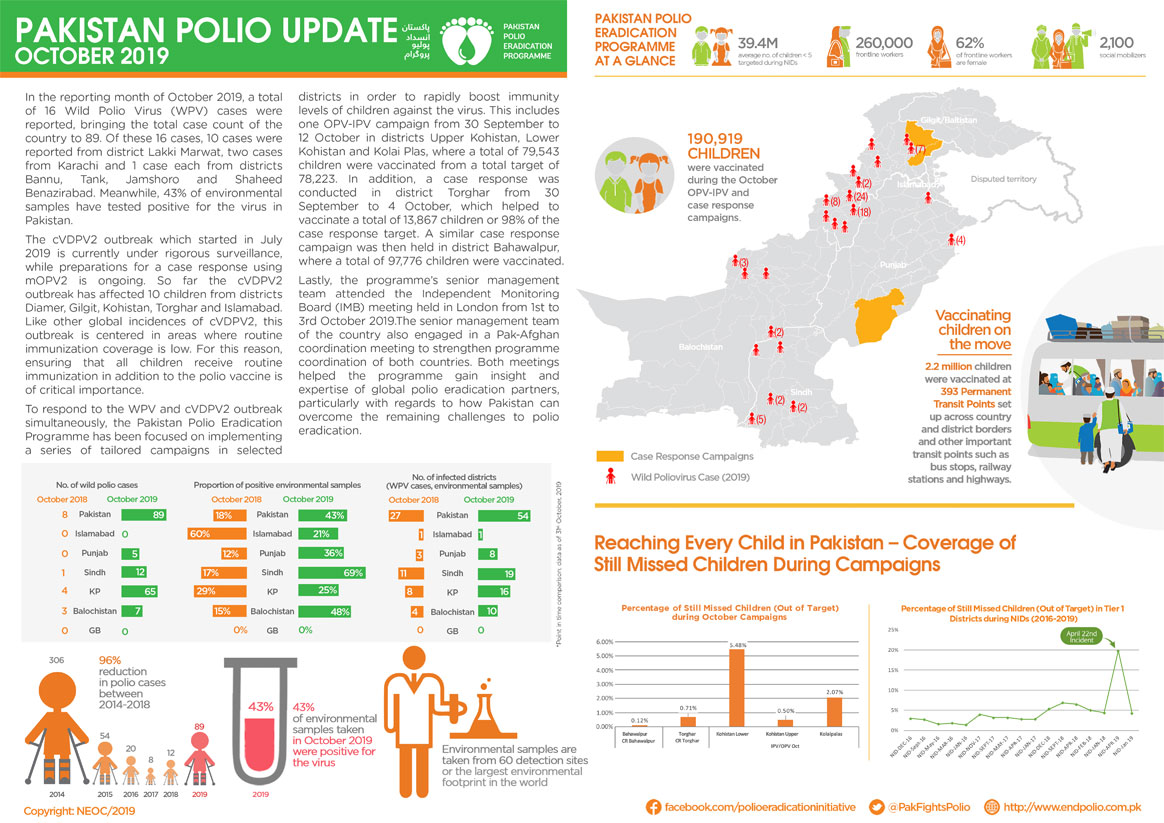

In October

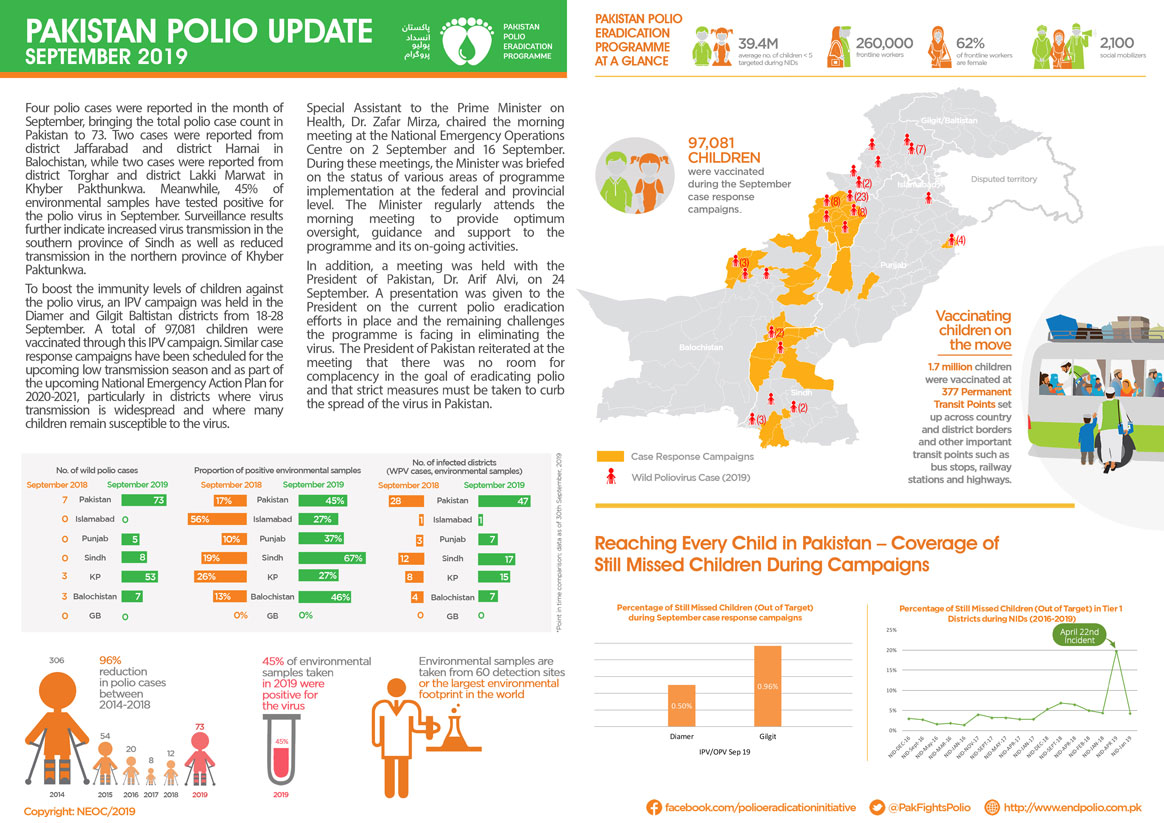

In September

“Tears were rolling down her cheeks. She was a true embodiment of pain and fatigue. She had huddled to her chest an eleven-year-old boy whose thin legs were hanging down, hampering her while she walked. I was stunned by the scene and stopped. I was curious to ask the woman what had happened to the child she was carrying. The poor woman wiped her tears to reply to me and revealed that out of her six children, three were suffering polio paralysis.”

Aziz Memon is narrating his first encounter with a child suffering from polio. The experience proved lifechanging. Over 22 years, he has risen to become one of the most influential philanthropists working to end polio in Pakistan.

22 years, 200,000 vaccine carriers, and millions raised to end polio

Aziz Memon is a good person to speak to if you want to get an insight into Rotary’s work in Pakistan. Chair of the Pakistan National PolioPlus Committee, Aziz is also a member of the International PolioPlus Committee. He has won multiple awards for his work to defeat the virus, and in October was announced as the first incoming Rotary Foundation Trustee to be appointed from Pakistan.

Aziz is most proud of his national committee’s work. He explains, “The committee has funded over 200,000 vaccine carriers for the entire EPI programme in Pakistan.”

“We have also supported vaccination at borders through permanent transit points, improved routine immunization at Permanent Immunization Centers, and helped provide basic medical care through female health workers. We have improved quality of life for families through solar filtration plants to provide clean water and have educated illiterate communities through providing speaking books. Rotarians create advocacy in schools, colleges, with Ulemas [Islamic religious scholars] and in their communities.”

With the support of Aziz and others, Rotary International has contributed millions of dollars to eradicate polio in Pakistan through the Government, WHO and UNICEF.

A chance to make history

The global drive to root out polio has some way to go still, with the poliovirus remaining in Afghanistan and Pakistan. To break the impasse an intensive, innovative and persistent effort is required.

“Rotary International’s mission to eradicate polio globally is our top priority and Rotary has taken this mission forward and helped and supported governments in other polio endemic countries to eradicate this terrible disease. It will be a privilege to be part of history when polio is eradicated, the second disease to be wiped out after smallpox,” Aziz explains.

Aziz reiterates that vaccine hesitancy and misinformation are two of the remaining challenges in the fight against polio in Pakistan.

“Misinformation spread through social media creates fear of the polio vaccine. Some security concerns still persist in tribal areas and there is weak accountability in places.”

In response, Rotary is supporting innovative strategies to address the challenges related to vaccine hesitancy. Aziz says, “Hesitancies must be skillfully addressed. We are working with Ulemas and religious scholars in all four provinces to create a positive image. Social media is playing a very strong role in averting misconceptions.”

Rotary is also a critical support to polio survivors who cannot afford their medical expenses. Aziz explains, “Rotary funds WHO to support a rehabilitation programme for polio victims. The Rotary Club of Karachi also sponsors a community project called the Artificial Limb Center which provided prosthesis, caliphers, crutches and wheelchair for polio victims and amputees as well as those injured in accidents.”

Dreaming of a polio-free Pakistan

Polio eradication in Pakistan has been a long journey but Aziz is motivated to overcome the remaining challenges.

“I motivate my fellows by nominating them for the Polio Free Service awards; publicizing their projects and activities in the monthly PolioPlus newsletter and honoring their services during the annual District Conference.”

A polio-free country is a dream for Pakistan. Reflecting on his feelings when India ended polio, to the joy of Rotarians worldwide, Aziz says, “It was good to know that a country like India could eradicate polio. It gives us hope that Pakistan can do it too, and we will soon be polio free.”

“Rotary was there at the beginning of the global effort to eradicate polio. If we stop now, polio may bounce back. We’ve done too much: we’ve made too much progress to walk away before we finish.”

The polio eradication campaign needs your help to reach every child. Thanks to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, your contribution to Rotary will be tripled. Donate now.

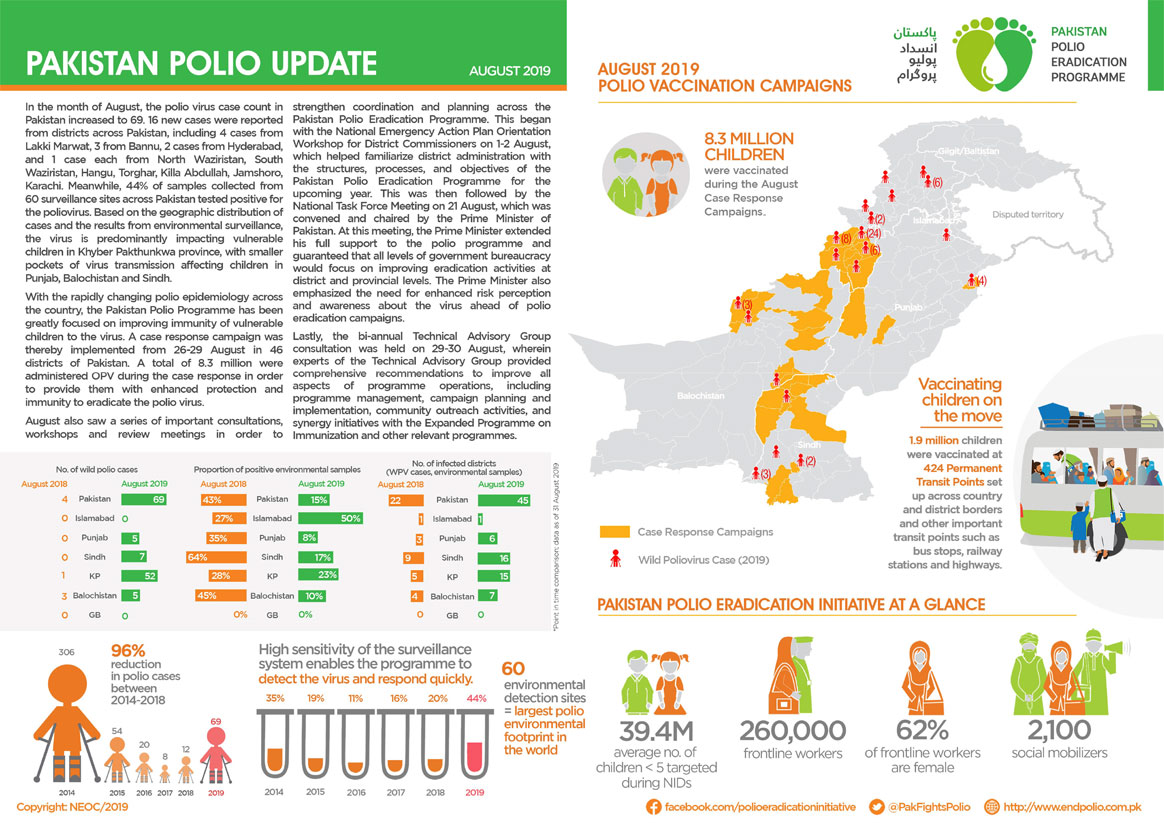

In August:

As the sun sets across Sindh province, exhausted polio eradication volunteers head home after a busy vaccination campaign. Each has personally vaccinated hundreds of children. In total, it has taken just a week for 9 million children under the age of five to receive two drops of oral polio vaccine, boosting their immunity against the virus.

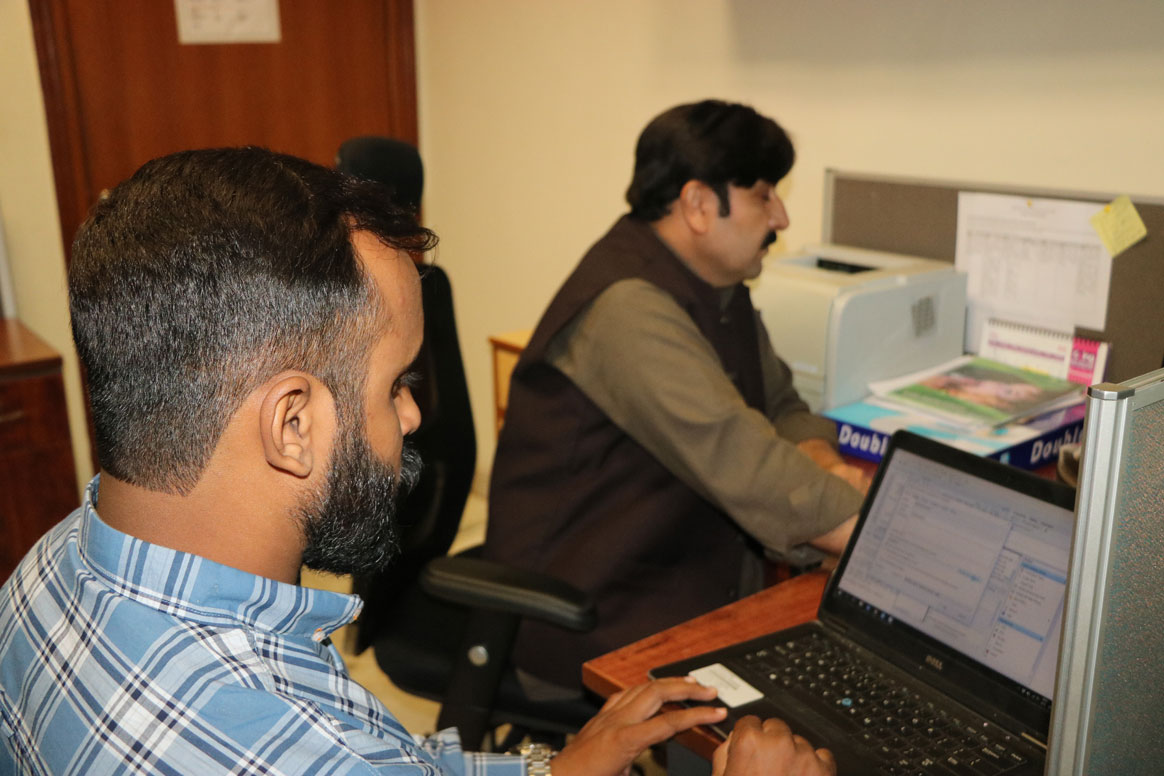

In the crowded office of Jan Sayyed, Ali Raza and Muhammad Bilal Wasi Jan however, work is only just beginning. They work in the Polio Eradication Data Support Centre, located in Pakistan’s biggest city Karachi. During the campaign, vaccinators fill in paperwork every time they distribute vaccine drops. They record the number of children reached with vaccines, their existing vaccination status, any vaccine refusals and whether the children are local to the area, or visiting.

Across a typical vaccination campaign, this generates data referring to over two million children, recorded on thousands of forms. It is the challenging job of Jan, Ali, and Bilal to label and classify all this data so that it can be uploaded to an online system and analyzed to improve the next campaign.

Data is the lifeblood of the polio programme

Waqar Ahmad, Technical Officer for Data at WHO Pakistan, believes that if immunization and disease surveillance represent the heart of the programme, then data is the lifeblood that helps the programme inch closer to vaccination.

Different kinds of reliable data help the programme make decisions based on evidence. For instance, data that shows a high rate of vaccine refusals in one area allows the programme to investigate the cause further and act to persuade parents of the importance of vaccination.

But creating effective systems for gathering, sorting, and analyzing high-quality data hasn’t been easy. It has required rethinking approaches, overcoming bumps in the road, and thinking beyond the usual parameters of data management.

Pakistan’s polio data journey

Data collection and record keeping in Pakistan’s polio eradication programme began in 1997. Originally, data was collected only in very specific circumstances, such as when cases of Acute Flaccid Paralysis were detected. Such limited data collection meant that broader programme activities could not be analyzed, which increased the chances that vaccination campaigns could be ineffective. Data on other aspects could ensure that logistics were right-sized, and that human resources were deployed where they were most needed.

In November 2015, the programme introduced an online database designed to provide real-time data, named the Integrated Disease Information Management System (IDIMS).

The IDIMS database is used to store pre-, intra- and post-campaign data relating to multiple areas, including vaccination, disease surveillance, human resource planning, logistics planning, and mobile data collection. Data inputted into IDIMS is directly available for viewing and analysis at the provincial, national, and regional level. It can be cross-referenced with other polio eradication databases.

Young Pakistanis like Jan, Ali and Bilal are part of the workforce that keeps the whole system online. Once they have labelled and classified the paper forms, they pass the data onto their colleagues to be digitized and analyzed.

What’s next for polio eradication data management?

Open Data Kit software

In the Data Support Centres, employees are constantly thinking about how to further improve the IDIMS system. Jan, Ali and Bilal note that digitizing the whole data collection and management process would make the system more efficient, as well as environmentally friendly.

Data collection using Open Data Kit (ODK) software offers a way to do this. The data collection process is the same as with paper forms, except information is recorded in a mobile based application. Once vaccinators are in an area with internet, the data is directly uploaded to the ODK server and the IDIMS server. The ODK system has been rolled out in some areas of Pakistan.

Gender innovations

Gender-disaggregated data represents a new area of work for the data management teams. Data included in the IDIMS database assists with gender-conscious campaign planning at the provincial level, while a separate system analyses gender-disaggregated information at the country level. Ensuring female vaccinators are recruited for campaigns is crucial, as women can often vaccinate children in places where for cultural reasons, men cannot.

Increasing user-friendly interfaces

As part of efforts to make systems user friendly, one year ago the polio programme launched online data profiles for Union Councils (UCs), the smallest administrative units in Pakistan. These profiles are available on the National Emergency Operation Centre data dashboard and allow polio programme staff to easily extract sizeable amounts of data about the local epidemiological situation within 30 seconds, as well as compare and analyze data for the past six years.

One of the most useful, innovative aspects of the UC profiles is that they collate information on children who were persistently missed during the last six campaign rounds, with information like contact details and the immunization history of the child. Such information assists the programme in follow-up engagement with the child’s parent or caregiver to encourage vaccination.

This requires speedy information sorting and uploading. Jan notes that his team is filing information more efficiently than they used to. This helps to ensure that details are up to date for nearly every town and village.

Over the coming months and years, further innovations will be introduced to improve data efficiency, range and quality.

Campaign by campaign, form by form, data handlers like Jan, Ali, and Bilal are helping to end polio.

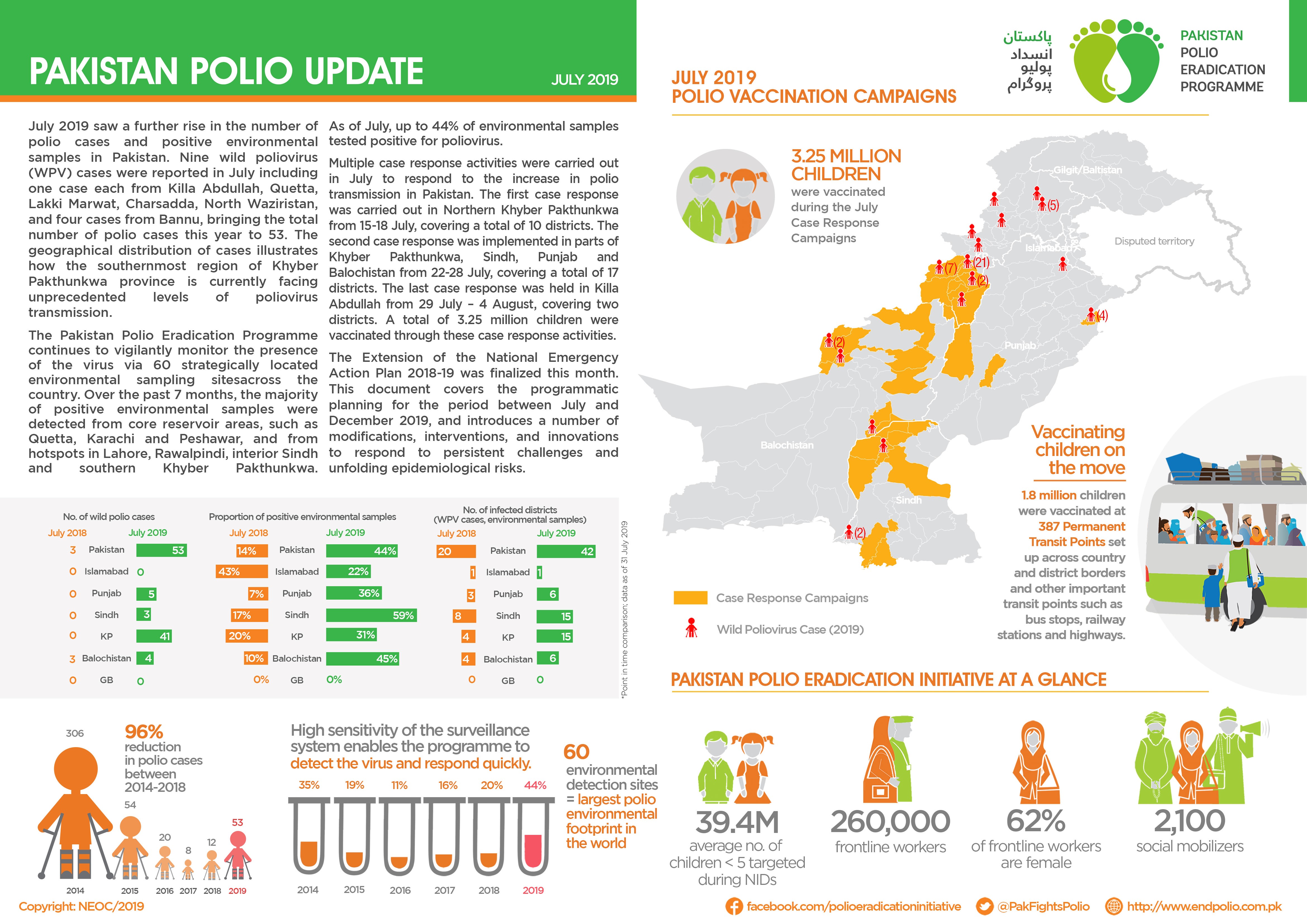

In July

In Union Council Kechi Baig, Quetta district, Balochistan province of Pakistan, Asma needs no introduction. When she talks, people listen. First, when she was one of the few female religious scholars at her local madrassa (school), and of late, as a champion for the polio programme.

For Asma, the segue into community health sensitization was quite natural. Her religious vocation as a teacher, also known as an Alima, and her life-long aspiration to help her community, came full circle when she became a religious support person (RSP) for the polio programme.

“I always wanted to become a doctor… but (it just so happened) I joined a madrassa and became an Alima…when I heard that the polio programme is looking for female RSPs, I took the opportunity. Even though I did not become a doctor, I can workwith doctors to serve humanity,” said Asma about her motivations.

As one of three female RSPs out of a team of 118, she has given unique credence to the polio efforts in her community. Kechi Baig accounts for a significant number of refusals to vaccinate. Community health workers are sometimes unable to make headway with refusal families. In such cases, Asma plays an important role as a faith-based counsellor, drawing upon her knowledge and expertise on religious teachings with communication skills and personal friendships within the community. Asma convinces 15-20 ‘hard refusal’ families in each vaccination campaign.

“I visit the households and leave with grandmothers convinced. As a madrassa teacher, I have seen that most females are unaware of religious teachings of Islam and the role of women to improve society. The polio fatwa (Islamic rulings) book proves to be very helpful because it contains authentic fatwas from venerated religious scholars.”

Re-appropriating polio through a religious lens

Asma realizes that bringing an attitudinal change through one-off encounters with refusal households is not enough. She saw the need for a long-term counselling relationship. Now, the polio programme team also conducts community engagement sessions with a cross-section of women across the community — from mothers to grandmothers to young students to women training at Asma’s madrassa—to raise awareness about polio.

“It is a great achievement being part of the training sessions about polio and health where I get to talk about the fatwa book. In almost every campaign I work with community health workers and convince 15 to 20 hard refusals for vaccination. It’s a big opportunity to save children from polio,” explained Asma.

Religious support persons, particularly women RSPs like Asma, play a very important role in mediating how people consider their choices for and against polio vaccination through the religious interface. By incorporating educative, spiritual, and medical knowledge, faith-based counselling goes a long way in neutralizing any refusal predispositions within the community.

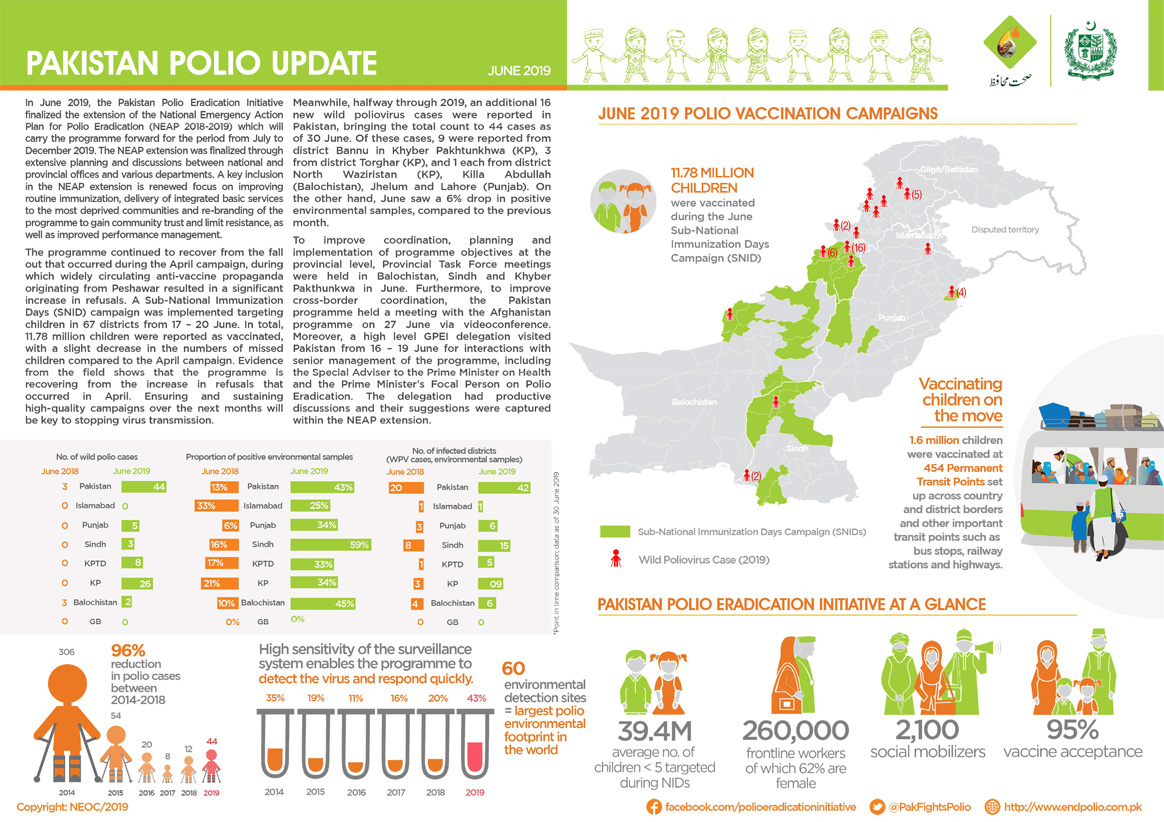

In June:

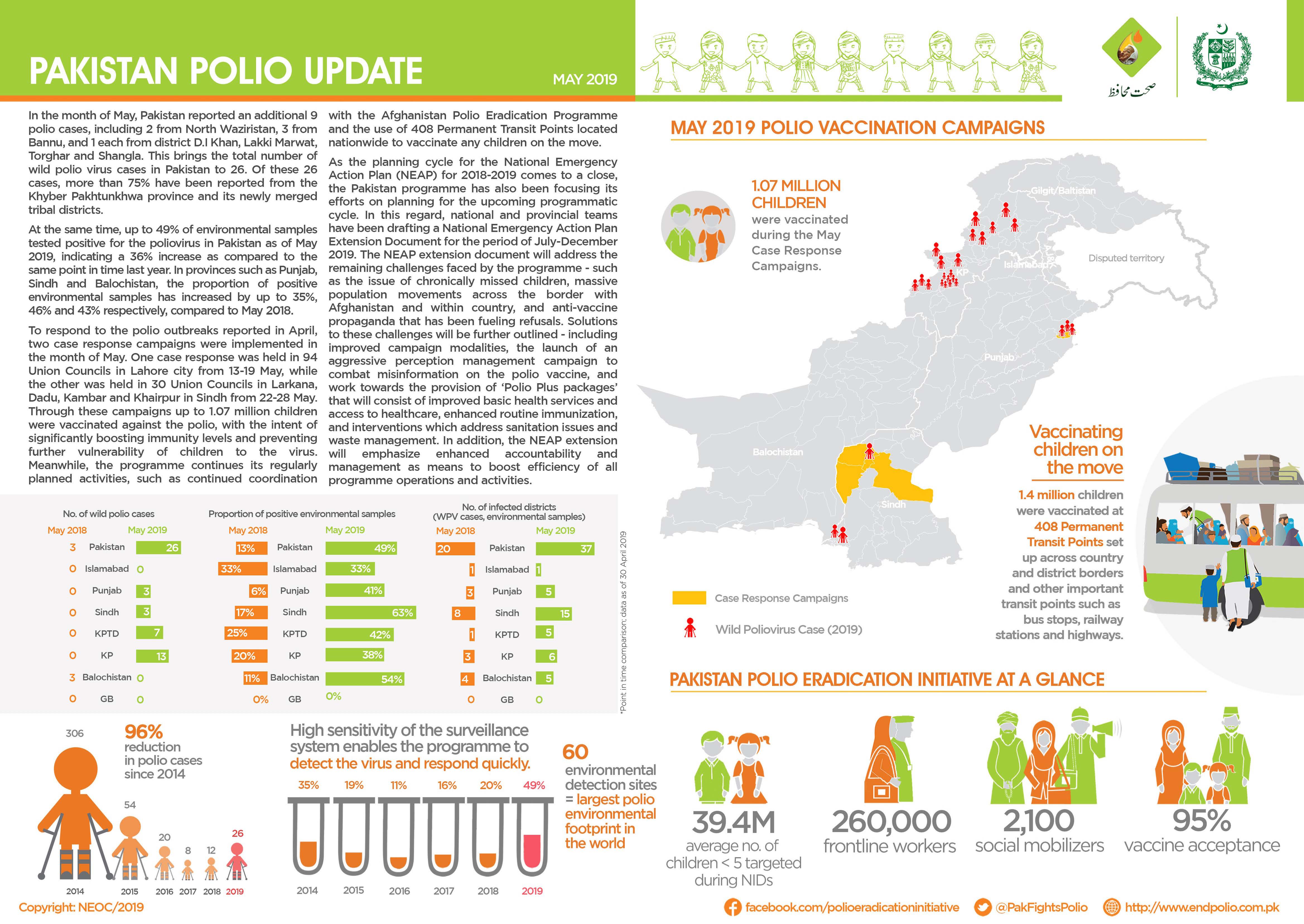

In May

A legion of supporters across neighbourhoods, schools, and households are creating a groundswell of support for one of the most successful and cost-effective health interventions in history: vaccination. These are everyday heroes in Pakistan’s fight against polio.

These thousands of brave individuals are championing polio vaccine within their communities to enlist the majority in the pursuit of protecting the minority — reaching the last 5% of missed children in Pakistan.

One of the major factors that determines whether a child will receive vaccinations is the primary caregiver’s receptiveness to immunization. The decision to vaccinate is a complex interplay of various socio-cultural, religious, and political factors. By educating caregivers and answering their questions, these Vaccine Heroes serve as powerful advocates for vaccination, even creating demand where previously there might have been hesitation. This is where everyday people step in to vouch for vaccination as a basic health right.

Here are some nuanced, powerful, and thought-provoking testimonies on their unwavering belief in reaching every last child:

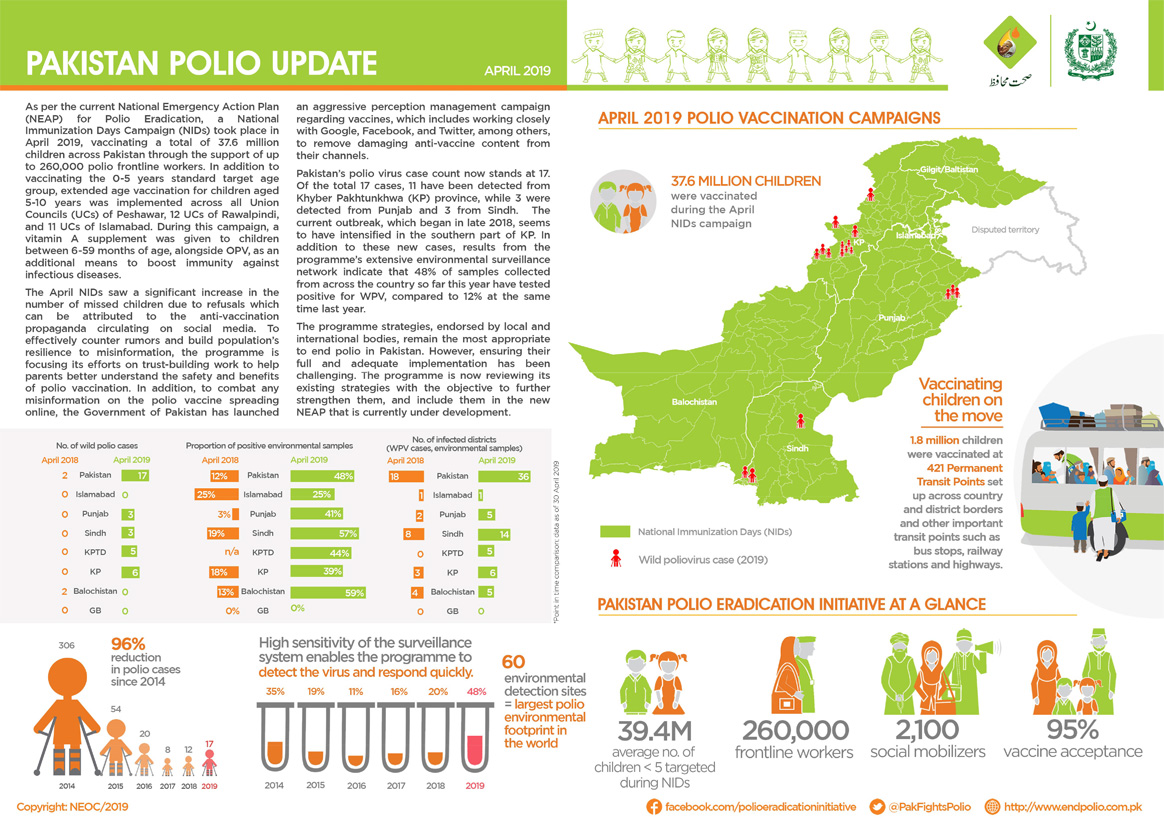

In April

The 72nd World Health Assembly, the governing body of the World Health Organization held by in Geneva, Switzerland is the biggest congregation of public health actors. Taking advantage of the critical mass of global leaders, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative hosted an event for polio eradicators, partners and stakeholders on 21 May 2019.

The event, To Succeed by 2023—Reaching Every Last Child, celebrated the GPEI’s new Polio Endgame Strategy 2019-2023. The five-year plan spells out the tactics and tools to wipe out the poliovirus from its last remaining reservoirs, including innovative strategies to vaccinate hard-to-reach children and expanded partnerships with the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) community and health emergencies.

The informal event brought together a cross-section of stakeholders – partners, health actors, non-health actors, supporters, donors, Ministers of Health of endemic countries, WHO Regional Director for the Eastern Mediterranean, and Polio Oversight Board members – alluding to strengthened and systematic collaboration in areas of management, research and financing activities in the last mile.

Dr Zafar Mirza, Pakistan’s Minister of State,Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination, took the stage and gave insight into country-level polio eradication efforts and the need for coordinated action with Afghanistan: “20 years ago, 30 000 children were paralyzed by polio in Pakistan. This year, 15 cases have been reported. While we have done a lot, it is clearly not enough. We are resolute in this conviction. We, together with Afghanistan, must make sure we eradicate polio for the sake of our children. Our science is complete, only our efforts are lacking. Along with the polio programme, the donors and the Afghan government, we will get to the finish line.”

Echoing similar sentiments, Dr Ferozuddin Feroz, Minister of Public Health of Afghanistan, said, “I would like to start by expressing thanks to all the partners for their support. As you know, Afghanistan has a very challenging context due to inaccessibility, refusals, gaps in campaign quality, low routine immunization coverage, and extensive cross-border movement. But, Afghanistan has made progress—five out of seven regions continue to maintain immunization activities. We view polio as a neutral issue and have developed a robust National Emergency Action Plan 2019. We appreciate the Polio Endgame Strategy 2019-2023. We believe coordination with Pakistan will help us deliver a polio-free world. We look forward to your continued technical and financial support to achieve the goal of polio eradication.”

Recognizing the long-standing commitment of the United Arab Emirates, a video was played showing the on-ground efforts of the Emirates Polio Campaign, working with communities and families in Pakistan in collaboration with the Global Polio Eradication Initiative and partners, and the Government of Pakistan. Thanks to the Emirates Polio Campaign, 71 million Pakistani children have been reached with 410 million doses of polio vaccine.

Dr Abdullahi Garba, Director for Planning, Research and Statistics, National Primary Healthcare Development Agency spoke on behalf of Professor Isaac F Adewole, Federal Minister of Health of Nigeria. Dr Garba harked back to the past as the GPEI plans for the future: “Nigeria started actively working to eradicate polio in 1988, at a time when we used to have up to a thousand cases every year. With all our innovation and efforts, I am pleased to inform you today that no wild polio case has been detected for the past 33 months. This feat was achieved through continuous efforts between the government, GPEI and partners, having diligent incidence reporting, reaching inaccessible children, and improving the quality of the polio surveillance immunization activities through strong oversight mechanisms in Nigeria. I know I also speak on behalf of all countries across Africa – we will achieve success.”

Rounding off the evening, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the World Health Organization Director-General and Chair of the GPEI Polio Oversight Board, took the stage to recount his first visit of the year to the polio endemic countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan, the progress made over decades, and the need to re-commit to the cause of ending polio. “Together with Regional Director Ahmed Al-Mandhari and Chris Elias of the Gates Foundation, we travelled to Pakistan and Afghanistan. We saw first-hand the commitments by both public and civil society leaders, which gave us a lot of confidence. The other thing that gave us confidence was seeing our brave health workers trudging through deep snow. And of course, our partners: Rotary, United Arab Emirates, CDC, UNICEF, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi. The last 30 years have brought us to the threshold of being polio-free…(which) lay out the roadmap that is the Polio Endgame Strategy 2019-2023. The Ministers of Afghanistan and Pakistan have also assured us that they will continue to work together in their shared corridor to finish polio once and for all.”

In 1988, the World Health Assembly passed a resolution to globally eradicate poliovirus, in what was meant to be “an appropriate gift…from the twentieth to the twenty-first century.”

As the GPEI plans for the future and its final push to ‘finish the job,’ it is clear that political and financial efforts need to ramp up in this increasingly steep last mile. As he concluded, Dr Tedros thanked committed partners like United Arab Emirates: “Global progress to end polio would not be possible without partners like the UAE. I would like to thank His Highness Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, and the UAE – a long-time supporter of the polio programme – for agreeing to host the GPEI pledging event this November at the Reaching the Last Mile Forum, a gathering of leaders from across the global health space held once every two years…let us join together to end polio.”

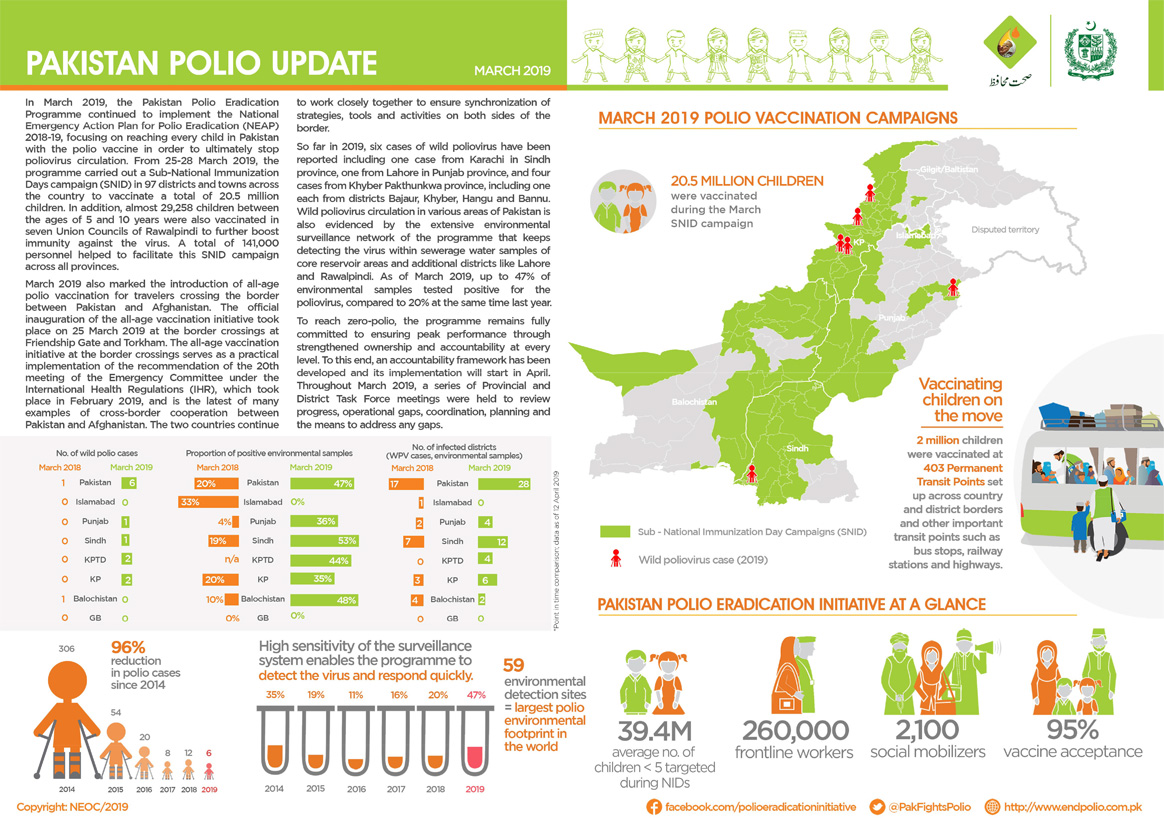

In March:

On both sides of the historical 2640-kilometre-long border between Pakistan and Afghanistan, communities maintain close familial ties with each other. The constant year-round cross border movement makes for easy wild poliovirus transmission in the common epidemiological block.

As a new tactic in their joint efforts to defeat poliovirus circulation, Afghanistan and Pakistan have introduced all-age polio vaccination for travellers crossing the international borders in efforts to increase general population immunity against polio and to help stop the cross-border transmission of poliovirus. The official inauguration of the all-age vaccination effort took place on 25 March 2019 at the border crossings in Friendship Gate (Chaman-Spin Boldak) in the south, and in Torkham in the north.

Although polio mainly affects children under the age of five, it can also paralyze older children and adults, especially in settings where most people are not well-immunized. Adults may play a role in poliovirus transmission, so ensuring that they have sufficient immunity is critical to simultaneously eliminating poliovirus from the highest risk areas on both sides of the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

This is particularly important at the two main border crossing points – Friendship Gate and Torkham – given the extensive amount of daily movement. It is estimated that the Friendship Gate border alone receives a daily foot traffic of 30 000. Travellers include women and men of all ages, from children to the elderly.

Pakistan and Afghanistan first increased the age for polio vaccination at the border in January 2016, from children under five years to those up to 10 years old. The decision was in line with the recommendations of the Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations (IHR) which declared the global spread of polio a “public health emergency of international concern”,

The all-age vaccination against polio at the border crossings serves a practical implementation of another recommendation of the IHR Committee: that Pakistan and Afghanistan should “further intensify crossborder efforts by significantly improving coordination at the national, regional and local levels to substantially increase vaccination coverage of travelers crossing the border and of high risk crossborder populations.”

As part of the newly introduced all-age vaccination, all people above 10 years of age who are given OPV at the border are issued a special card as proof of vaccination. The card remains valid for one year and exempts regular crossers from receiving the vaccination again. Children under 10 years of age will be vaccinated each time they cross the border.

Before all-age vaccination began at Friendship Gate and Torkham, public officials held extensive communication outreach both sides of the border to publicize the expansion of vaccination activities from children under 10 to all ages. Radio messages were played in regional languages, and community engagement sessions sensitized people who regularly travel across the border. Banners and posters were displayed at prominent locations.

Deputy Commissioner for Khyber District in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Mr Mehmood Aslam Wazir, inaugurated the launch of All-Age Vaccination by vaccinating elderly persons at the Torkham border crossing. “Vaccination builds immunity and it is necessary for children to be vaccinated in every anti-polio campaign. The polio virus is in circulation and could be a threat to any child. The elders in our community could be carrier of the virus and take along the virus from one place to another, therefore, vaccination of every traveller, of all ages and genders, crossing Pakistan-Afghanistan border will be the key determinant to interrupt polio virus transmission in the region, and the world.”

The introduction of the all-age vaccination at border crossings is the latest example of cross-border cooperation between Pakistan and Afghanistan. The two countries continue to work closely together to ensure synchronization of strategies, tools and activities on both sides of the border.

On 15 March 2019 in Islamabad, representatives from the Embassy of Japan and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) were given a general update on the progress of the Polio Regional Lab and the surveillance network. Thanks to Japan’s funding, 70% of the latest molecular biology equipment has been procured, installed and made operational. JICA representatives also toured the facility and the works in process.

The Government of Japan through JICA is a long-standing and committed donor to the polio eradication efforts by funding initiatives and broader immunization activities in Pakistan since 1996.

As a part of its more recent commitment, JICA is supporting Pakistan in strengthening disease surveillance through a state-of-the-art equipment of the Regional Reference Laboratory at the National Institute of Health in Islamabad.

The Pakistan Regional Polio Lab will go a long way in facilitating poliovirus detection in stool samples and the environment. At present, the lab tests more than 30,000 stool samples from people with paralysis and 950 environmental samples each year, including samples from both Afghanistan and Pakistan. The new soon-to-be operational lab equipment will speed up the ability to process and respond quickly wherever the poliovirus may be hiding. This is critical work in ensuring Pakistan targets its last remaining core reservoirs of poliovirus.

In this last mile of polio eradication, support from JICA is crucial and much appreciated. Pakistan is one of the last remaining polio endemic countries in world, along with Afghanistan and Nigeria. The political and financial commitment from the Government of Japan over the years has already helped Pakistan in reducing the number of polio cases by 96% since 2014. With only 12 cases reported in 2018, Pakistan has a fighting chance of finally consigning polio to the history books.

The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)

The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) assists and supports developing countries as the executing agency of Japanese ODA. In accordance with its vision of “Inclusive and Dynamic Development,” JICA supports the resolution of issues of developing countries by using the most suitable tools of various assistance methods, such as technical cooperation, ODA loans and grant aid in an integrated manner.

In February:

Like many Pakistani women, Hafiza and Sahiqa start their days in the early morning, when other household members are still asleep. They tackle their domestic chores before beginning their official duties – as polio frontline workers.

“I get up by 5:00 am, if I am to prepare properly for a productive day. I need to manage my home chores before I can set out for my official work. I have to prepare breakfast, lunch, lunch boxes for my children and do the dishes. After that I clean the house and then I have to prepare my kids for school. After sending them to school, I leave for the office around 7:30 am,” Sahiqa explained.

Sahiqa (29) is from Quetta in Balochistan province and Hafiza (22) is from Islamabad. In their careers as Pakistan’s cadre of Lady Health Workers, they deliver house-to-house preventative and curative care to underserved communities, in particular women and children in urban and rural slum areas Locally recruited and community-based, these female health workers are also central to progress against polio in Pakistan’s complex environment.

Across Pakistan, thousands of women do the vital work of immunization in an environment that can be harsh, distressing and even dangerous. They balance this work with the demands of their own children and families, and they put their own needs last.

The women’s official workday starts at 8:00 am and is marked by interactions with the community every day. As part of their work, Lady Health Workers educate women about the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, on better hygiene practices, supporting the advancement of women and children’s health and wellbeing. They knock on every door of their assigned areas to vaccinate children against polio during frequent immunization campaigns.

In Pakistan, women currently make up more than 56% of more than 260 000 frontline polio workers. Having women on the frontlines has been a game changer for polio eradication in Pakistan, given the trusted roles they have in communities and the fact that they are more likely to be allowed to take the crucial step across the thresholds of people’s homes and ensure access for all children to vaccines. Female polio frontline workers including vaccinators, campaign coordinators, supervisors and social mobilizers often work in extremely challenging circumstances to ensure children are protected against polio.

“I remember one chronic refusal family. It was such a difficult task to convince the women of the house to vaccinate their children. We engaged in many discussions and I explained to them that if the polio drops were not beneficial, would I give them to my own kids?

After a lot of convincing, I was able to persuade the women. I was so happy to have managed to convert a chronic refusal case and protect the kids in that house against polio,” Sahiqa said.

Despite multiple challenges, especially working in a conservative province like Balochistan, the health workers remain steadfast and intensely committed when it comes to achieving their goals. They have become creative problem solvers who are motivated by every refusal they convert. The challenges act as fuel and have helped them develop the skills they need to navigate the complexities of the job in this cultural context.

“While performing my job, remaining calm and controlling my emotions are the most difficult skills that I have drawn from these challenges. During this job, I learnt a lot how to avoid taking things personally as this helped me focus on the real objective. With the passage of time, I have realized the importance of maintaining firm boundaries in order to facilitate respectful communication with people,” said Hafiza.

There are different reasons why women in Pakistan make the choice to become polio frontline workers. Some have to support their families and some have to earn money for their studies. Many women take this job because it is the best opportunity to move ahead in life. The defining characteristic of most female polio frontline workers is a passion to serve humanity.

“I feel lucky to have my husband beside me, supporting me in every endeavour. He is also a polio worker and he feels that women have better access to the homes in the communities and can relate to the mothers therefore they have a definite advantage in gaining the trust of the homemakers in the community,” Sahiqa said.

The women’s official duty ends with the setting sun, but at home domestic responsibilities await. They have to prepare dinner for the family and then help children complete homework. The idea of eight hours of uninterrupted sleep is a dream for them, but they sleep with the knowledge that they are doing important work, and doing it well.

Hafiza and Sahiqa are individual women, but they are also a reflection of every female worker who is part of the fight against polio. The polio eradication programme would not be where it is today without the contributions of hardworking women dedicated to ending polio.

Polio eradication efforts are as much rooted in the social realities as they are in the technological tools. The success of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative comes down to one simple action: the knock on the door, when the child’s caregiver greets the health worker.

Why do caregivers let vaccinators enter their homes? The caregiver’s decision to vaccinate is influenced by many moving parts: social, cultural, economic, and religious. Women health workers and leaders are able to transcend many of these boundaries as they are not only health workers; they are members of that community – someone’s neighbour, friend, aunt, cousin or grandmother.

Polio-endemic, at-risk, and outbreak countries regularly engage women as health officials in immunization activities, constituting about 68% of the frontline workforce. In Nigeria, 99% of frontline workers are women, followed by 56% in Pakistan and 34% in Afghanistan. But their strength in numbers is not the only reason why women are crucial to polio eradication efforts, they are, in fact, behavioural change agents.

Here’s a look at some of the resilient and inspiring women working to eradicate polio in their communities – in their own words:

Reposted with permission from Rotary.org

Dr Ujala Nayyar dreams, both figuratively and literally, about a world that is free from polio. Nayyar, the World Health Organization’s surveillance officer in Pakistan’s Punjab province, says she often imagines the outcome of her work in her sleep.

In her waking life, she leads a team of health workers who crisscross Punjab to hunt down every potential incidence of poliovirus, testing sewage and investigating any reports of paralysis that might be polio. Pakistan is one of just two countries that continue to report cases of polio caused by the wild virus. In addition to the challenges of polio surveillance, Nayyar faces substantial gender-related barriers that can hinder her team’s ability to count cases and take environmental samples. From households to security checkpoints, she encounters resistance from men. But her tactic is to push past the barriers with a balance of sensitivity and assertiveness.

“I’m not very polite,” Nayyar says with a chuckle. “We don’t have time to be stopped. Ending polio is urgent and time-sensitive.”

Women are critical in the fight against polio, Nayyar says. About 56% of frontline workers in Pakistan are women. More than 70% of mothers in Pakistan prefer to have women vaccinate their children.

That hasn’t stopped families from slamming doors in health workers’ faces, though. When polio is detected in a community, teams have to make repeated visits to each home to ensure that every child is protected by the vaccine. Multiple vaccinations add to the skepticism and anger that some parents express. It’s an attitude that Nayyar and other health workers deal with daily.

“You can’t react negatively in those situations. It’s important to listen. Our female workers are the best at that,” says Nayyar.

With polio on the verge of eradication, surveillance activities, which, Nayyar calls the “back of polio eradication”, have never been more important.

Q: What exactly does polio surveillance involve?

A: There are two types of surveillance systems. One is surveillance of cases of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP), and the second is environmental surveillance. The surveillance process continues after eradication.

Q: How are you made aware of potential polio cases?

A: There’s a network of reporting sites. They include all the medical facilities, the government, and the hospitals, plus informal health care providers and community leaders. The level of awareness is so high, and our community education has worked so well, that sometimes the parents call us directly.

Q: What happens if evidence of poliovirus is found?

A: In response to cases in humans as well as viruses detected in the environment, we implement three rounds of supplementary immunization campaigns. The scope of our response depends on the epidemiology and our risk assessment.

We look at the drainage systems. Some systems are filtered, but there are also areas that have open drains. We have maps of the sewer systems. We either cover the specific drainage areas or we do an expanded response in a larger area.

Q: What are the special challenges in Pakistan?

A: We have mobile populations that are at high risk, and we have special health camps for these populations. Routine vaccination is every child’s right, but because of poverty and lack of education, many of these people are not accessing these services.

Q: How do you convince people who are skeptical about the polio vaccine?

A: We have community mobilizers who tell people about the benefits of the vaccine. We have made it this far in the program only because of these frontline workers. One issue we are facing right now is that people are tired of vaccination. If a positive environmental sample has been found in the vicinity, then we have to go back three times within a very short time period. Every month you go to their doorstep, you knock on the door. There are times when people throw garbage. It has happened to me. But we do not react. We have to tolerate their anger; we have to listen.

Q: What role does Rotary play in what you do?

A: Whenever I need anything, I call on Rotary. Umbrellas for the teams? Call Rotary. Train tickets? Call Rotary. It’s the longest-running eradication program in the history of public health, but still the support of Rotary is there.

In January:

Pakistan’s polio programme relies on the efforts of thousands of specialized workers, but there is one group almost everyone relies on: the drivers.

In the endgame of eradication, reaching zero transmission requires a vast network of expertise— from epidemiologists to community advocates to data managers and health workers. But without drivers, many of these people would not be able to do their work.

Polio eradication entails wide-ranging nationwide vaccination campaigns. In Pakistan, this means targeting more than 38 million children under the age of five. Reaching every single child without an organized fleet of vehicles is almost impossible. Polio programme drivers do not plan activities in operations centres, but they have a real on-ground impact in the fight against polio.

“ I think whether you are a polio eradication officer, data personnel, technical staff, a consultant, a member of the communication team or a driver, every single employee is playing a very significant role in polio eradication efforts.”

Bahudar Shah (53), Islamabad, Pakistan

“It doesn’t matter whether you’re in the driver’s seat or the passenger seat, driving is an unavoidable and essential part of the polio programme, especially here in Pakistan, where the push for eradication is at such a sensitive and critical point. I have spent the last 20 years as a driver with WHO’s polio programme, always with the same focus: saving Pakistani children from this disease and securing a better future for them.”

“For polio field officers, duty starts around 8 am, but the driver’s duty starts early in the morning whether they are traveling directly to field or to the office. I personally feel that when I am in the field, I am responsible for the safety of my assigned vehicle as well as that of the officer.”

Alam Sher Khan (52), Islamabad, Pakistan

“I joined in 2002 and since then I have learned, I am working for the welfare of future generations. At work, I apply the “safety first” approach to every part of my job. I think, I am not only driving but I also act as a guide and security guard for my field officer. Because I drive with different field officers at different places, before the commencement of field work I orient my officer about the social norms, customs and security situation of the area. I also advise them to remain close to the vehicle. It is very essential to remain close to the vehicle for a possible quick escape in case of some emergency situation.

“The thing I enjoy as a driver with the polio programme is the satisfaction of my passenger: the field officer. When my field officer is satisfied, I am satisfied, and for this I have worked to enhance my skills.”

Ghulam Asghar (59), Islamabad, Pakistan

“For the last 16 years, I have played a significant role in polio eradication in Pakistan. My level of responsibility as a driver is very high. Polio eradication is a programme that requires strong teamwork. While performing my duty with different field officers, I assist them in finding local vaccination teams and convincing the community of the importance of vaccination, and I clear any hurdles so they can do their jobs during case investigation, campaign monitoring and LQAS.

“When my officer covers refusals during campaign monitoring, it gives me the most satisfaction as I feel that we have saved a child from permanent disability. When there is some refusal I actively assist my officer to counter that refusal. I also advocate within my local community and try to satisfy them about the efficacy of the vaccine.”

Jamil Abbasi (46), Islamabad, Pakistan

“I have been a driver for the polio programme for the last 14 years. I think whether you are a polio eradication officer, data personnel, technical staff, a consultant, a member of the communication team or a driver, every single employee is playing a very significant role in polio eradication efforts.

“I have a strong wish to see Pakistan polio free. Although I am not directly involved in eradication activities, indirectly I am contributing to better implementation and success of routine immunization efforts by safely transporting field officers to their assigned duty areas. I am proud that I am a part of hardworking team who are trying to defeat the polio virus.”

In December