In April:

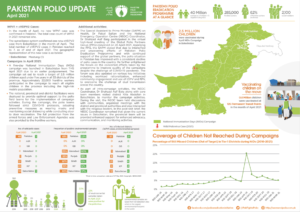

- No case of WPV1 was confirmed

- 2,500,000 children were vaccinated during the April National Immunization Days (NIDs) in Balochistan

- 800,000 children were vaccinated 126 Permanent Transit Points

In April:

Meeting virtually this week at the 74th World Health Assembly (WHA), global health leaders and ministers of health noted the new Global Polio Eradication Initiative Strategic Plan 2022-2026 and highlighted the importance of collective action to achieve success.

Member States emphasised the urgency of implementation of the strategic plan and urged the WHO Secretariat and Member States to build on recent advances to keep surveillance high, ensure sustained, improved coverage in campaigns and respond rapidly to outbreaks. Several Members States welcomed the establishment of a new EMRO Ministerial Regional Subcommittee on Polio Eradication and Outbreaks, and roll-out of the novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2) to more effectively and sustainably address outbreaks of circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPVs). The Minister of Health of Egypt, Dr Hala Zaid, as a Co-Chair of the Regional Sub-Committee said: “The Regional Subcommittee offers a new, ministerial-level channel to galvanize political support, leverage funding, particularly domestic funding, and raise the profile of polio as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Its establishment reflects the firm commitment of the Eastern Mediterranean Region to do whatever it takes to stamp out poliovirus transmission and achieve eradication.”

Dr Ahmed Al-Mandhari, the Regional Director for the Eastern Mediterranean, addressed the delegates and noted a year of hard work across the Region. He emphasised the critical step of establishing the ministerial Sub-Committee to ensure more coordinated support for the remaining wild poliovirus-endemic and polio outbreak-affected countries in the Region. Speaking of the new vaccine, Dr Al-Mandhari said, “We are also at the dawn of what we hope will be a new era in responding to VDPV type-2 outbreaks, with an improved vaccine, the novel oral poliovirus type 2, approved for Emergency Use Listing and soon to be used in the Region.”

Member States noted support for local community, progress on closing outbreaks and welcomed efforts to unite with other initiatives to close gaps in immunization. The WHA paid tribute to female frontline workers and highlighted their role in building community relationships. Amid the new COVID-19 reality, the WHA also expressed deep appreciation for the GPEI’s ongoing support to COVID-19 response. WHO’s Deputy Director-General, Dr Zsuzsanna Jakab, highlighted the value of the polio infrastructure in addressing public health emergences, noting that the polio network has been the first in line of defence for COVID-19 response in many countries, and now providing valuable support to the rollout of Covid-19 vaccines. “It is our chance to retain the polio knowledge and expertise to build back stronger and more robust health systems. If we don’t act now, we will lose this enormous opportunity,” said Dr Jakab.

The Regional Director for the African Region, Dr Matshidiso Moeti, thanked African countries and partners for rapidly restarting and innovating to deliver polio activities after a pause during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially following the successful certification of eradication of wild polioviruses last year in the region. Integrating polio functions into other programmes will be critical to maximising the gains against this disease, she said, and to leveraging the wealth of expertise and experience that has been built.

Rotary International welcomed the new strategy and its priority on integration and extended collaboration with partners, as well as its focus on gender equality. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, highlighted the new strategy’s alignment with the Immunization Agenda 2030 and Gavi’s new 5-year strategy, and shared importance of reaching 0-dose children and missed communities with comprehensive and equitable immunization services.

Aidan O’Leary, WHO Director for Polio Eradication, addressed delegates, saying: “Wild poliovirus transmission is restricted to Afghanistan and Pakistan, and while we have seen a sharp decrease in incidence this year, this is no time for complacency. Gaining and sustaining access to all children in Afghanistan and increasing coverage of missed children in core reservoir areas of Pakistan remain the key challenges, and we must all work together to overcome these to achieve and sustain zero cases. At the same time, we must continue to respond to cVDPV2s. The solutions focus not just on the new nOPV2, but also more timely detection, more timely and higher quality outbreak response and strengthening essential immunization services in zero-dose communities and children, aligned with the IA2030 agenda. The new strategy addresses the broader needs of communities through expanded integration and partnership efforts along six distinct workstreams. Implementation will be strengthened through a more systematic approach to performance, risk management and accountability at all levels.”

The new strategy – Delivering on a Promise – will be officially launched at a virtual event on 10 June 2021. Details about the event are available here.

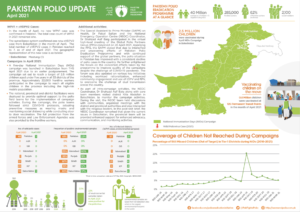

In March:

In his English writing class, Mujahid Miran was asked to write an essay titled the “Aim of life”. This was a space for the students to imagine who they could be and what they saw themselves as when they grew up.

Miran wanted to be a captain in the army and he eagerly shared this ‘aim of life’ in his essay. After his hopes made it to the page, his teacher immediately shot it down: There was no way he would make it, she told him, because he had polio.

Born in 1985, Miran grew up in Kohat and contracted polio when he was two. This was a year before the Global Polio Eradication Initiative was founded in 1988, leading to a worldwide vaccination campaign to fight the spread of the disease. In the decade of the ’80s, the estimated number of cases was over 350 000 per year, while the disease was still prevalent in 125 countries. With focused efforts around the world to eradicate the poliovirus, the number of paralytic cases was reduced by 99.99% with 42 cases in 2016.

For Miran, school was among the most challenging periods of his life. “School life was generally very hard. It must be easier for polio survivors to study in special schools, but in a usual school, I was always referred to as langra, mazoor (derogatory words in Urdu for people with disabilities). I was always made to feel different.”

The challenges were frequent, never letting him forget that he couldn’t walk from one leg. “Among the things that would hurt a lot was sports class or recess. “Every time kids would be chosen for a sports activity, I was completely sidelined – as if I wasn’t even there.” he says.

Academically, Miran always performed well in class and would usually be among the top three students. I always had among the best grades, but I would never be nominated to be the class monitor or get a position as part of the student council, he says. “Every week I’d go to my teacher and ask her why I was never nominated because other students who would be poorer than me academically would be chosen instead. A part of me knew even back then that it was my disability, but now looking back, I know it was exactly that.”

After having lived with polio for 33 years now, Miran is now based in Karachi and is part of a small seafood export business. He buys seafood from factories in Pakistan to sell in southeast Asia and makes an income for the commission he makes per sale.

Miran is able to independently support his family of his wife and two children, aged six and two, but the everyday realities of living with polio make the smallest of tasks harder.

“There is such little awareness in Pakistan, and it’s even within government institutions. I had to get my special driver’s license and when I went to get it made, the officer on duty asked me to raise my shalwar in front of a group of people and stand on one foot to prove I had a disability, he adds. “The humiliation is too much.”

This virus has also been an obstacle in maintaining friendships, as most places for leisure in Pakistan have no access for people with disabilities. “Plus, there is also so much shame in it. I was in Dubai once and I was walking with a friend who turned around to me and said that the way I was walking was embarrassing for him. This virus impacts your life in every way.”

Last year, Africa was declared wild polio-free after Nigeria, the last remaining country in the region that had polio and accounted for more than half of all global cases less than a decade ago, had no cases of wild poliovirus for the fourth year running.

Today, Pakistan and Afghanistan are the only two endemic countries in the world and global efforts continue to vaccine children in this epidemiological block, and finally make the dream of a polio-free world possible.

Miran says this interview is his personal effort to spread awareness on polio. “I talk to everyone in my friends and family circle who have young children. I give them my example and tell them they can’t afford to miss out on vaccination. I am very regular with my children’s vaccination too. Whenever polio teams come to our house, I make sure the children take polio drops.”

At many times in the interview, Miran mentions how the physical pain caused by the disease is often unbearable. “I almost never express how much pain I feel because people will think I’m asking them for financial help or wanting their sympathy. But I just want everyone to know that living with polio is hard. Very, very hard.”

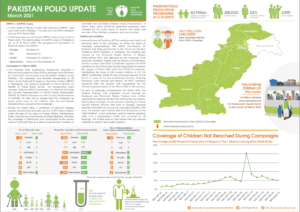

In January

With masks on their faces and sanitizers in their pockets, an immunization team makes their way through the narrow lanes of Lahore’s historic old city.

“Our children are like flowers and these anti-polio drives help them grow up healthy and strong,” says Zubair, who along with his colleague Afzal is part of Pakistan’s 260,000-strong frontline vaccinator workforce.

It is the second day of the National Immunization Days (NID) campaign, which launched on 21 September, and the third immunization drive after a four-month suspension of door-to door campaigns due to the risks associated with COVID-19.

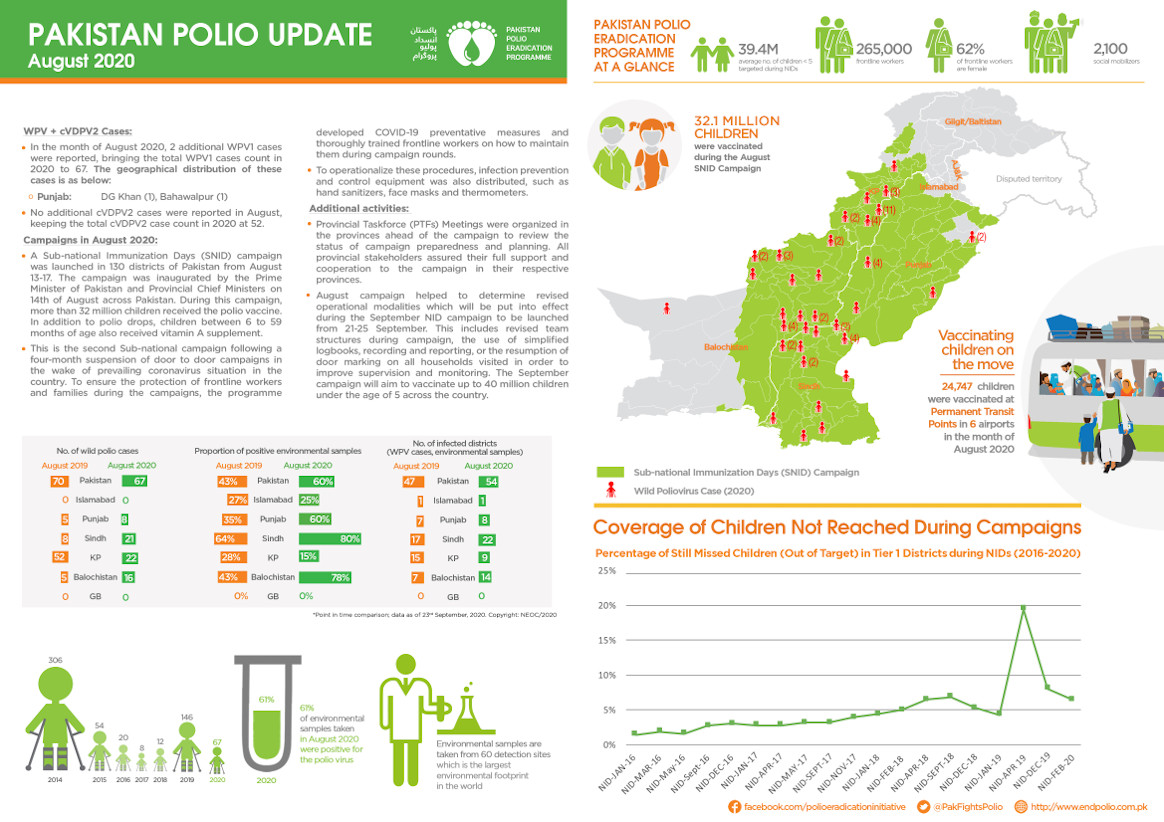

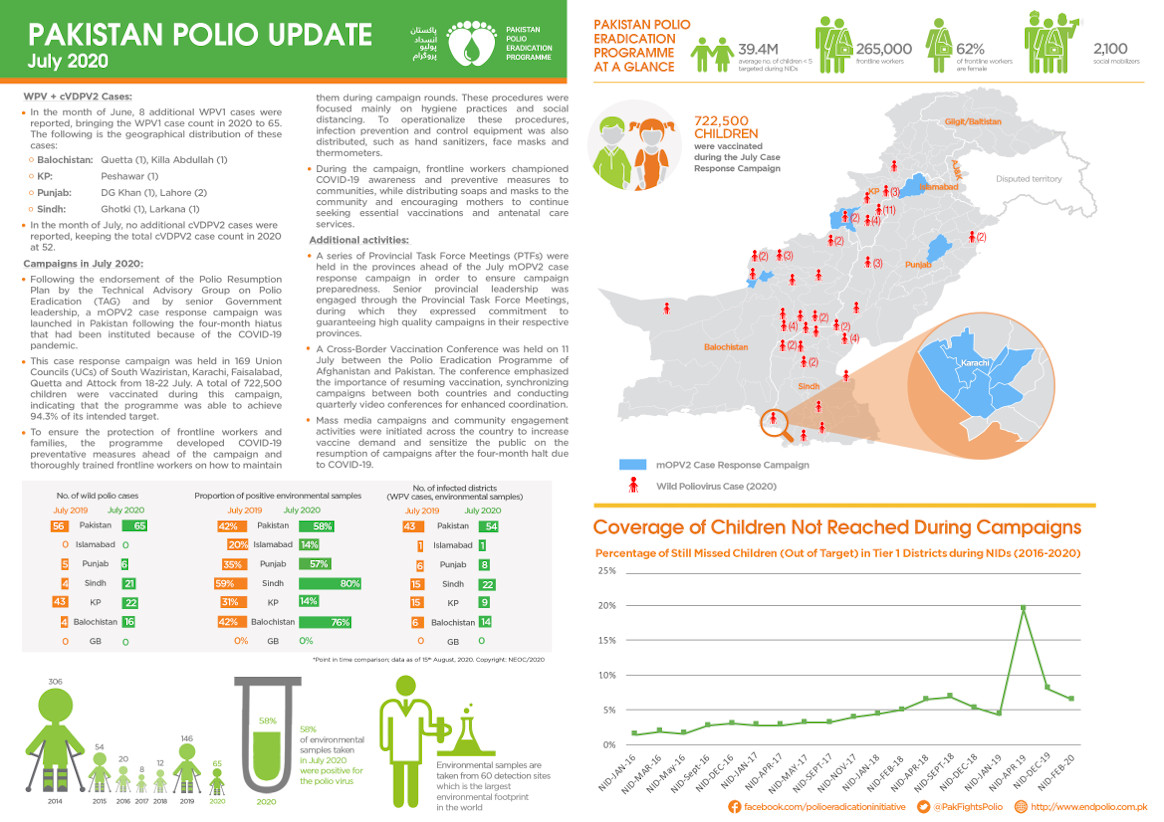

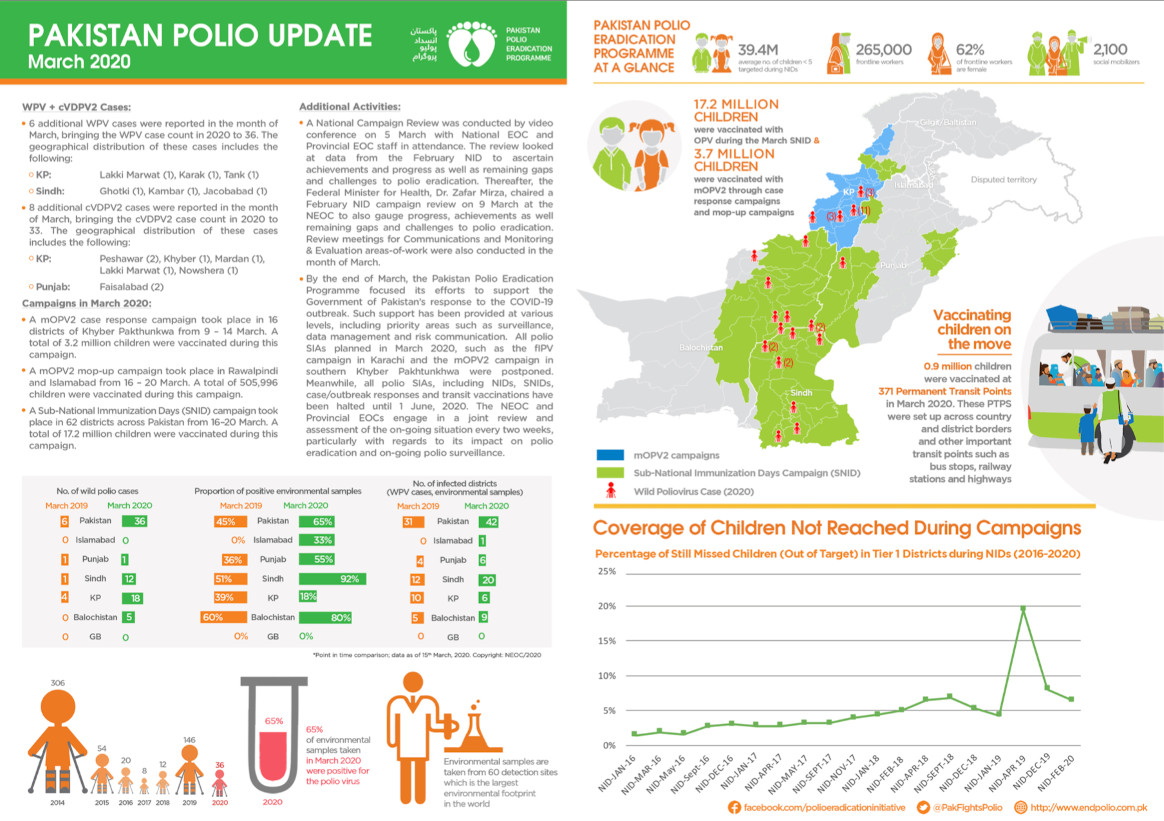

After polio campaigns were stopped in March 2020, the number of polio cases in Pakistan continued to increase. An initial small-scale round of vaccinations resumed in July, when over 700,000 children were reached. A second round went ahead in August, where 32 million children were vaccinated across the country. In both campaigns, vaccinators took precautions to prevent the spread of COVID-19, including wearing masks and regularly washing hands.

Making their way from the crowded streets of Taxila Gate, the polio team reaches a historic cultural hub of Lahore city called Heera Mandi.

In this neighbourhood, the team knocks on one door after another. “Sister, do you have children under five at home?”, they say.

When the answer is yes, one of the vaccinators stands to the side while Zubair hands them a hand sanitizer. They all stand at a safe distance from each other, to remain compliant with COVID-19 safety measures, and to make sure the dual message of the necessary fight against both polio and COVID-19 reaches home.

Zubair says that since the resumption of immunization campaigns in Pakistan, parents have been more enthusiastic to ensure their children are vaccinated.

Next door, a Maulana (a religious cleric) answers. When he sees the polio team, he immediately goes back inside. Team members worry that he may reject the vaccine, but soon enough, he returns with his two children.

“Did you ever believe that the polio vaccination was a conspiracy?,” the Maulana is asked. In some parts of Pakistan, false rumours about the vaccine have damaged confidence in immunization, with sometimes devastating results for children subsequently infected with polio.

“No Sir, only a fool can think like that,” he replies.

Afzal, another member of the immunization team, says that he finds his work fulfilling because it allows him to directly speak to parents about polio and explain that they can give their children a healthy future by vaccinating them.

With a physical disability, Afzal often faces discrimination based on his health condition. He explains that this hasn’t prevent him from pursuing his ambitions.

“I never allowed my disability to become an obstacle. I completed my master’s degree while attending regular classes at college, and now I have been working with the polio programme for nine years.”

“If a family is hesitant during a polio campaign, I approach the parents,” he says. “I show the parents my polio-affected leg and ask them if they really want their child to have one too. This changes hesitation to acceptance.”

Health workers like Zubair and Azfal are working every day to achieve the dream of ending polio in Pakistan. With their effort and the efforts of thousands like them, the September campaign successfully reached over 39 million children across the country. These promising results, achieved during a pandemic, are a testament to an ongoing commitment to overcome challenges and move Pakistan closer to a polio-free future.

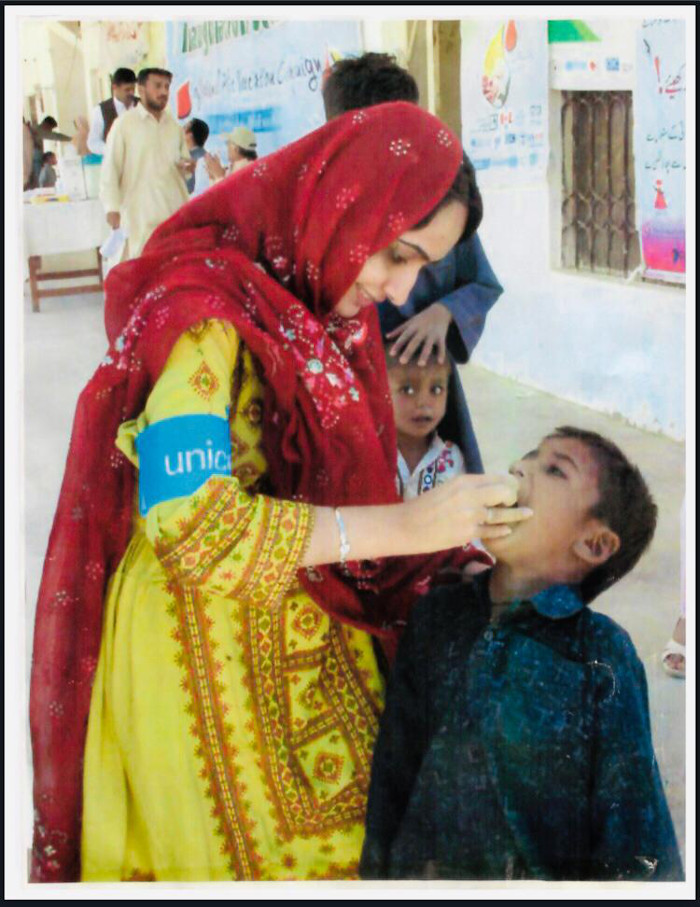

In 2018, Jawahir Habib, a Programme Officer in UNICEF’s Polio Outbreak Team based in Geneva, received a letter. It was from a Pakistani woman she had met while working in the Quetta block – one of the most high-risk polio areas of Pakistan. The letter read:

“I have four daughters, and my daughters are in school because of the polio programme. I can afford to teach my girls which my husband opposed. Now they too can get education and live an independent life. I will make sure every child is covered and this is my mission.”

Words like these inspired Jawahir and set her on a path to a ten year career in polio eradication. She recalls her first day at work, “That day was very interesting – I was chased by dogs in the Kharoatabad area of Quetta. Although I managed to save myself, I spent the whole day crying and realizing that polio workers face this type of adversity day to day. I knew that I must become a part of this and ten years later, I am still working to eradicate polio”.

The more Jawahir became involved in the polio programme, the more she witnessed women facing social challenges. At the time, suboptimal campaigns in the polio reservoirs was one of the major hurdles faced by the programme and the number of missed children in Quetta block remained very high. More than 70% of frontline workers were male or non-locals, resulting in limited access to households.

It was then that the Pakistan programme began looking at success stories from other parts of the world, including Nigeria, where Volunteer Community Mobilizers (VCMs) were making significant strides in eradicating polio. The need to build a network of local female health workers who were trusted and could gain access became more and more clear. Balochistan, where Jawahir is originally from, is one of the most remote and conflict-ridden areas of Pakistan and strict conservative religious and cultural norms, tribal conflicts and insecurity would prove very challenging.

When Jawahir’s team started recruiting, training and deploying women frontline workers in Quetta block, she was told it was impossible. “I was told that there was no way we could manage a workforce comprising of women working in these areas”. As a team leader, Jawahir had to create an enabling environment for women to work, keep them motivated and ensure systems were in place for them to reach every child in the block. “At a personal level, I had to lead by example and show everyone that women could work in these difficult areas, face resistance and achieve what a man could – in this case, even more.”

Jawahir knew well the challenges of being a young woman in a male dominated society. Born in Kili Mengal Noshki, a remote village in Balochistan bordering Afghanistan, she faced a lot of challenges. Despite this, Jawahir got her bachelors degree, a postgraduate diploma in public health management and a masters degree in health communication from the University of Sydney.

While working on polio, she had to work twice as hard as men, facing threats, gender biases and intimidation. What kept her inspired and motivated was being a part of something much bigger which she believed could change the world.

During this time, Jawahir’s team managed to identify, train and deploy a workforce of 3500 Community Based Workers (CBV) where 85% of the frontline vaccinators were women. During the first few campaigns 700,000 children in the core reservoir area were registered and vaccinated and more than 150,000 children who had previously been missed during the campaigns were mapped and given oral polio vaccine. One of the notable success of female teams was seen in Chaman Tehsil, on the border with Afghanistan, where within four months, the number of chronic vaccine refusals went from 15,000 to 400 children. That was a huge success for Pakistan’s polio eradication goal.

Jawahir attributes the success to the brave women who have made a major contribution to their society. She sees the empowerment of woman in one of the most difficult parts of the world as GPEI’s legacy of social change now and for the future. “Imagine a workforce of thousands of women having access to every household – imagine the venues we have for routine immunization, for nutrition, health and even education”.

The COVID-19 pandemic has compounded a rise in polio cases in Pakistan in 2019 and 2020, and polio eradicators once more have their work cut out to bring down virus transmission and protect populations.

“I believe now it is the responsibility of each and every one of us in the polio programme, whether a polio worker in Chaman or an Officer in Geneva, to ensure that this disease is eradicated once and for all. We will carry on no matter the hurdles and obstacles placed on our road, and we will finish the race.”

In a year marked by the global COVID-19 pandemic, global health leaders convening virtually at this week’s World Health Assembly called for continued urgent action on polio eradication. The Assembly congratulated the African region on reaching the public health milestone of certification as wild polio free, but highlighted the importance of global solidarity to achieve the goal of global eradication and certification.

Member States, including from polio-affected and high-risk countries, underscored the damage COVID-19 has caused to immunization systems around the world, leaving children at much more risk of preventable diseases such as polio. Delegates urged all stakeholders to follow WHO and UNICEF’s joint call for emergency action launched on 6 November to prioritise polio in national budgets as they rebuild their immunization systems in the wake of COVID-19, and the need to urgently mobilise an additional US$ 400 million for polio for emergency outbreak response over the next 14 months. In particular, Turkey and Vietnam have already responded to the call, mobilising additional resources and commitments to the effort.

The Assembly expressed appreciation at the GPEI’s ongoing and strategic efforts to maintain the programme amidst the ‘new reality’, in particular the support the polio infrastructure provides to COVID-19-response efforts. Many interventions underscored the critical role that polio staff and assets play in public health globally and underline the urgency of integrating these assets into the wider public health infrastructure.

At the same time, the GPEI’s work on gender was recognized, with thanks to the Foreign Ministers of Australia, Spain and the UK for their roles as Gender Champions for polio eradication.

Delegates expressed concern at the increase in circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) outbreaks, and urged rapid roll-out of novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2), a next-generation oral polio vaccine aimed at more effectively and sustainably addressing these outbreaks. This vaccine is anticipated to be initially rolled-out by January 2021.

Speaking on behalf of children worldwide, Rotary International – the civil society arm of the GPEI partnership – thanked the global health leaders for their continued dedication to polio eradication and public health, and appealed for intensified global action to address immunization coverage gaps, by prioritizing investment in robust immunization systems to prevent deadly and debilitating diseases such as polio and measles.

In August

Welcome to Pehlwan Goth, Pakistan. A low-income neighbourhood on the edge of Karachi city, it is home to many families from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province who have moved here for work.

An open sewage drain lined with litter runs the length of the settlement. Cattle are often seen grazing near the heaps of garbage. It is a high-risk area for polio, and virus is regularly detected in the environment.

Samreen, a 25-year-old Polio Area Supervisor, leads a team of four community health workers in the area.

“I started working with the Polio Eradication Programme four years ago and I am happy to say that we have made a lot of progress here. This is my neighbourhood; this is where I grew up and this helps me immensely. People here listen to me, especially the women, and I know most of the children by name,” says Samreen.

There are around 32,000 children under five years of age in Pehlwan Goth. In April 2019, parents of around 3,000 children refused the polio vaccine. Through the hard work of supervisors like Samreen however, now over 80% of these children have received vaccines.

“I am in charge of an area that has 210 households with 196 children. In 2019, families of more than 50 children refused vaccines. That’s almost one fourth of all the children in my area,” said Samreen.

“Building trust takes time, and we continued engaging with community members, visiting families, listening to their concerns, and explaining the benefits of vaccination. Today, we have only eight refusal cases out of the previous 50. I will try my level best to bring this number down to zero during the polio campaign next month.”

“But for me, it is not just about just converting refusals during every campaign, I want all families to understand the benefits of vaccines in the long run and ensure the immunization of their children against polio and other diseases.”

Her rapport with families is apparent during house visits. A family with three children, who had refused vaccination in previous months, agreed that their children could this time receive the life-saving polio drops.

Confronting misconception

Building trust with the community has not been an easy task. Samreen is supported by a social mobilizer as well as a local religious support person. The team members work together to address misconceptions and raise awareness of good health practices among caregivers in Pehlwan Goth.

“We speak the same language and our homes are in the same area where we work. It is easier to communicate with people when you are part of the same community,” said Maulana Mohammad Hanif, the religious support person in Samreen’s team.

Sometimes, however, it can take only one negative social media video or news item to reignite refusals and overturn all their efforts.

“The process takes time. The work is tough but I am grateful to Allah for this job, which allows me to feed my family, and contribute to a noble cause, which will save future generations of Pakistanis,” added Maulana Mohammad Hanif.

It’s clear that Samreen and her team will do whatever it takes to deliver a polio-free future to all 196 children in their care. Pakistan and Afghanistan are the final two polio endemic countries in the world and there are still many challenges that remain.

It is the local efforts of teams like Samreen’s that will make all the difference – by listening to communities, building trust and ensuring rapport, they are playing a crucial role to bring their country closer to ending polio.

In July

Vaccinators in countries including Afghanistan, Angola, Burkina Faso and Pakistan took to the streets this month to fill urgent immunity gaps that have widened in the under-five population during a four month pause to polio campaigns due to COVID-19.

Campaigns resumed in alignment with strict COVID-19 prevention measures, including screening of vaccinators for symptoms of COVID-19, regular handwashing, provision of masks and a ‘no touch’ vaccination method to ensure that distance is maintained between the frontline worker and child. Only workers from local communities provided house-to-house vaccination to prevent introduction of SARS-CoV2 infection in non-infected areas.

Although necessary to protect both health workers and communities from COVID-19, the temporary pause in house-to-house campaigns, coupled with pandemic-related disruptions to routine immunization and other essential health services, has resulted in expanding transmission of poliovirus in communities worldwide. Modelling by the polio programme suggests a potentially devastating cost to eradication efforts if campaigns do not resume.

In Afghanistan, 7858 vaccinators aimed to vaccinate 1 101 740 children in three provinces. Vaccinators were trained on COVID-19 infection control and prevention measures and were equipped to answer parents’ questions about the pandemic. Through the campaign, teams distributed 500 000 posters and 380 000 flyers featuring COVID-19 prevention messages.

In Angola, 1 287 717 children under five years of age were reached by over 4000 vaccinators observing COVID-19 infection prevention and control measures. All health workers were trained on infection risk, and 90 000 masks and 23 000 hand sanitizers were distributed by the Ministry of Health.

In Burkina Faso, 174 304 children under five years of age were vaccinated in two high-risk districts by 2000 frontline workers. Vaccinators and health care workers were trained on maintaining physical distancing while conducting the vaccination. 41 250 masks and 200 litres of hand sanitizer were made available through the COVID-19 committee in the country to protect frontline workers and families during the campaign.

In Pakistan, almost 800 000 children under the age of five were reached by vaccinators in districts where there is an outbreak of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus. Staff were trained on preventive measures to be followed during vaccination, including keeping physical distance inside homes and ensuring safe handling of a child while vaccinating and finger marking them.

“Our early stage analysis suggests that almost 80 million vaccination opportunities have been missed by children in our Region due to COVID-19, based on polio vaccination activities that had to be paused,” said Dr Hamid Jafari, Director for Polio Eradication in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. “That’s close to 60 million children who would have received important protection by vaccines against paralytic polio.”

Over the coming months, more countries plan to hold campaigns to close polio outbreaks and prevent further spread, when the local epidemiological situation permits.

“Our teams have been working across the Region to support the COVID-19 response since the beginning of the pandemic, as well as continuing with their work to eradicate polio,” said Dr Hamid Jafari. “We must now ensure that we work with communities to protect vulnerable children with vaccines, whilst ensuring strict safety and hygiene measures to prevent any further spread of COVID-19”.

Dr Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa, commented, “We cannot wait for the COVID-19 pandemic to be contained to resume immunization activities. If we stop immunization for too long, including for polio, vaccine-preventable diseases will have a detrimental effect on children’s health across the region.”

“The campaigns run by the Polio Eradication Programme demonstrate that mass immunization can be safely conducted under the strict implementation of COVID-19 infection prevention and control guidelines.”

Nida, a polio community worker in Lahore, is glued to her mobile phone. But this is not a leisurely conversation with a friend. She is messaging a mother in her neighbourhood who is worried about COVID-19.

Since the pandemic began, polio programme workers across the country have pivoted to use messaging applications, especially WhatsApp, to disseminate COVID-19 prevention and care messages to communities. This is one aspect of the extensive support being offered by the Pakistan polio programme to the COVID-19 response.

Over the last few months, the polio programme has produced a suite of videos, digital pamphlets and posters on COVID-19 prevention and care in formats that can be easily shared and viewed via messaging platforms.

“This is an example of resilience – how the polio team has adapted to the change and found an effective way to support the people across the country during the COVID-19 crisis,” said UNICEF’s Dennis Chimenya, the Communication Task Team lead of the Pakistan Polio Programme. “Standing with the community during these challenging times will certainly contribute to building further trust in polio frontline workers.”

Engaging religious and community influencers

Engaging religious leaders and local influencers is a critical part of effective community outreach. Now, many are receiving messages and calls from polio community workers seeking their support for the COVID-19 response.

Qari Zafar, a religious cleric at a mosque in Lahore, was a staunch opponent of restrictions to religious gatherings.

“Initially, I was totally against the idea of asking people to pray at home. I felt that people need to pray together at the mosque during this difficult time and support each other,” said Zafar.

“Then I started receiving messages and posters from [polio community workers] Nida and Uzma about how the coronavirus spreads. Our chats helped me understand the seriousness of the situation.”

“I have started making announcements through the mosque loudspeakers, asking people to offer their prayers at home, even during Ramadan. I also regularly message my followers, reminding them about healthy practices.”

The ‘new normal’ for community outreach work

“Messaging platforms have become the ‘new normal’ to carry out community outreach activities,” said Muhammad Asif, a polio frontline worker in Quetta, Balochistan province.

At the north west frontier region of Pakistan, in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, the polio communication teams have created 63 group chats, tailored for different audiences, to amplify COVID-19 preventive messages.

In Punjab, similar groups have helped the programme reach over 110,000 people with digital posters and leaflets. Messaging applications are also helping the programme communicate with religious pilgrims and other mobile populations, whose travel patterns put them at greater risk of becoming infected with COVID-19.

In Sindh, WhatsApp has helped the programme reach over 200,000 people at risk, 4,000 religious leaders, 3,000 influencers and more than 80 journalists with awareness materials and guidelines for ethical reporting.

“The potential of using such platforms under the present circumstances is huge. Yes, our movement is limited but we have to find a way to do our job and to ensure that the correct messages reach the right audience on time,” said Fatima Fraz, Communication for Development Specialist for the polio programme in Sindh.

“Just imagine, there are 14,000 polio frontline staff in Karachi. If each staff member sends out the messages and then follows up by phone with just 20 people, that’s 280,000 people reached right then and there.”

WHO has launched a dedicated messaging service in languages including Arabic, English, French, Hindi, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Urdu and Somali to keep people safe from coronavirus.

Find out how to join WHO’s Health Alert on WhatsApp.

In March 2020, polio social mobilisers from the UNICEF-run Immunization Communication Network (ICN) provided routine immunization referral services to over 37,000 children in southern and eastern Afghanistan.

The polio programme’s routine immunization efforts in Afghanistan have made important gains, especially in the country’s east, in the areas bordering Pakistan. Polio social mobilisers support mother and child health referral services, and help families keep track of their children’s health records. As the mobilisers are recruited from their community, they know the families in their neighborhood and can trace each child’s planned immunization schedule from birth.

It is critical that routine immunization continues throughout the pandemic to protect children from life-threatening diseases including polio. Polio mobilisers have found their work is even more valued during the COVID-19 response.

Masoud, a polio mobiliser, says ‘’I used to announce the immunization sessions through the Mosque but not all the targeted children were brought to the health facility. Now through the ICN support to routine immunization, the number of missed children has reduced due to tracking of every child in the community and coordinating with the health facility.”

“This is critical during the ongoing pandemic, as families are not sure if they can leave their homes to take their children to the health facility for immunization. The polio mobilisers are their guide in the community.’’

In March

In 2003, Melissa Corkum received a call that would change her life. The World Health Organization wanted to interview her for a position in their polio eradication team. Like most people who are hearing about polio eradication for the first time, the story compelled her, and she packed her bags to embark on a new adventure. Seventeen years later, she remains a dedicated champion of polio eradication.

A self-proclaimed ‘virus chaser’, Melissa has worked in all three polio endemic countries – Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria. She found inspiration in her first field job in Nigeria, where she realized the scale of the polio eradication programme and that she was a part of something tremendous in public health history.

“I was amazed and inspired when I first saw the efforts of the front-line workers delivering vaccines to the doorstep. It may seem simple to deliver a couple drops into a child’s mouth, but when you see it in motion for the first time, it is truly remarkable,” Melissa said.

To this day, Melissa remains in awe of the work required to make ‘reaching every child’ possible. From mobilizing financial resources, to getting vaccines where they need to be while keeping them cool. From the microplanning to ensure all children and their houses are on a map, to the mobilization of champions in support of polio and immunization. Along the way, the stewards of these processes play an essential role to deliver the polio vaccine.

Melissa has worn many hats during her time in polio eradication, but her current role may be the most challenging yet. As the Polio Outbreak Response Senior Manager with UNICEF, she must answer the formidable challenge of containing outbreaks, using her expertise to inform global policy, strategy and operations.

To do this Melissa spent 80% of her time in the field prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, working with partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), Ministries of Health and local health workers.

Her work is a mix of challenge and excitement – the challenges of containing outbreaks, including those affected by the COVID-19 emergency – and excitement in developing new tools and methods to overcome the evolving challenges that present barriers to eradicating polio.

“There is never a dull day no matter what hat you may be wearing within this programme. If we are going to put an end to polio for good, we are going to have to fight the fight on a number of fronts – endemics and now the emerging issue of outbreaks in a post-COVID world,” said Melissa.

“The key is a willingness to do whatever it takes to get the job done.”

At times, Melissa felt the weight of the enormous challenges to eradicate polio, especially during her time in Afghanistan, where protracted conflict has complicated efforts to deliver basic services to the most vulnerable. Melissa often reflects on her time as Polio Team Lead there and the emotional rollercoaster she faced trying to stay ahead of the virus, while watching the tragedy of war unfold in the country.

“But when I felt down, I would pick myself up and get ready to face the next challenge. I found hope and inspiration in the resilience of the Afghan people, especially the women who worked in the polio programme, risking their lives and demonstrating a courage that stood out amidst all the difficulties.”

Melissa sees gender as one of the keys to polio eradication. She firmly believes that the only way to tighten the gaps in the system is by involving and empowering women equally in all roles across the programme, and that the only way to reach every child is to ensure their caregivers are equally informed and engaged in the decision making process.

“Unless we involve more women in the programme in certain corners of the world, we will continue to reach the same children and miss the same children, making polio eradication ever more difficult,” Melissa said.

“Change won’t happen if we don’t change the way we think about involving women. We need to listen to their views and open the doors for more women to join and participate equally from the community level and all the way to the leadership, decision-making level.”

Melissa was born in a small town in Nova Scotia, Canada. Her views on the critical involvement of women and gender equality in the polio programme very much align with her government’s Feminist Aid Policy. The Government of Canada has been a long-time champion of polio eradication and recently generously pledged C$ 190 million to assist the GPEI achieve its objectives of polio eradication.

Greater gender equity is one of the legacies that the polio programme is working to leave behind after eradication. Reflecting on her career, Melissa explains what keeps her working to defeat polio after all these years.

“It is so inspiring to be part of something tangible and something that is completely possible if we commit ourselves to doing everything possible to find every last child”.

It was a somber day when Ihsanullah was told that two of his youngest children will never be able to walk again. His two year old daughter Safia, and Masood, his five month old son, were both diagnosed with polio.

When they began running a high fever in December, Ihsanullah rushed them to the nearest hospital in the city of Tank, Pakistan. After a series of tests, doctors confirmed that both children had contracted polio. Further investigations revealed that neither child had been vaccinated during any previous routine immunization or polio campaign rounds.

Like many other parents in his village, Ihsanullah had never accepted the polio vaccine. “I had a negative opinion about vaccination from the start. Many people told me that the polio vaccine was made of haram[forbidden] ingredients and was part of a larger conspiracy to make Muslim children sterile,” he said.

A farmer and labourer by profession, 27-year-old Ihsanullah lives in a village named Latti Kallay in Khyber Pakthunkwa, Pakistan. Polio teams often face hesitancy from communities in Latti Kallay during campaign rounds, with many parents citing religion as the primary reason for refusing the polio vaccine. In Tank city and the immediate surrounding areas, six wild polio virus cases were reported in 2019.

Sadly, it sometimes takes a case of polio for communities to fully realize the importance of vaccinating their children. Asghar and Khadim, neighbours of Ihsanullah, told polio teams that they had started ensuring that their children are vaccinated, despite being staunch refusers of the vaccine previously.

Ihsanullah said, “It pains me to imagine that Safia and Masood will never be able to walk again. If I knew that this would be the outcome, I would never have stopped the polio teams from vaccinating my children. I deeply regret my decision, but I will make sure that my other children are vaccinated”.

For now, the COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated the temporary pause of polio vaccination campaigns. This leaves unvaccinated children who cannot access routine immunization services vulnerable to paralysis. The situation also underlines the vital importance of increasing trust in vaccines amongst parents, so their children are protected from polio no matter what happens.

Gohar Mumtaz, the Union Council Polio Officer of the district, has hope. He says that a routine immunization session with the community, conducted before the pandemic spread to Pakistan, seemed to be more popular than usual. “Although there is still hesitancy, the situation seems to be improving. People will understand the need to vaccinate and no child will suffer like Safia and Masood in the future.”

To overcome barriers to polio eradication, the Pakistan polio programme conducted a top-to-bottom review during 2019. Areas where improvement is required were identified, and innovations introduced. This is vital work, as there are many other children in Pakistan besides Safia and Masood whose futures have been marred by the poliovirus. Last year saw increased transmission of the poliovirus across all provinces with a total of 147 wild cases reported.

The COVID-19 pandemic has added an additional hurdle to defeating polio in Pakistan. It is vital that the programme makes up for lost time as soon as it is safe to conduct house-to-house vaccination activities again. Whilst the pandemic is ongoing, the programme continues to build trust with communities by providing information about COVID-19 as well as the poliovirus. Where routine immunization continues in health centres, polio personnel are emphasizing the importance of maintaining children’s vaccination schedules as far as possible.

In a time when our health feels especially precious, Ihsanullah, Safia and Masood’s story serves to remind us why vaccination is so important.

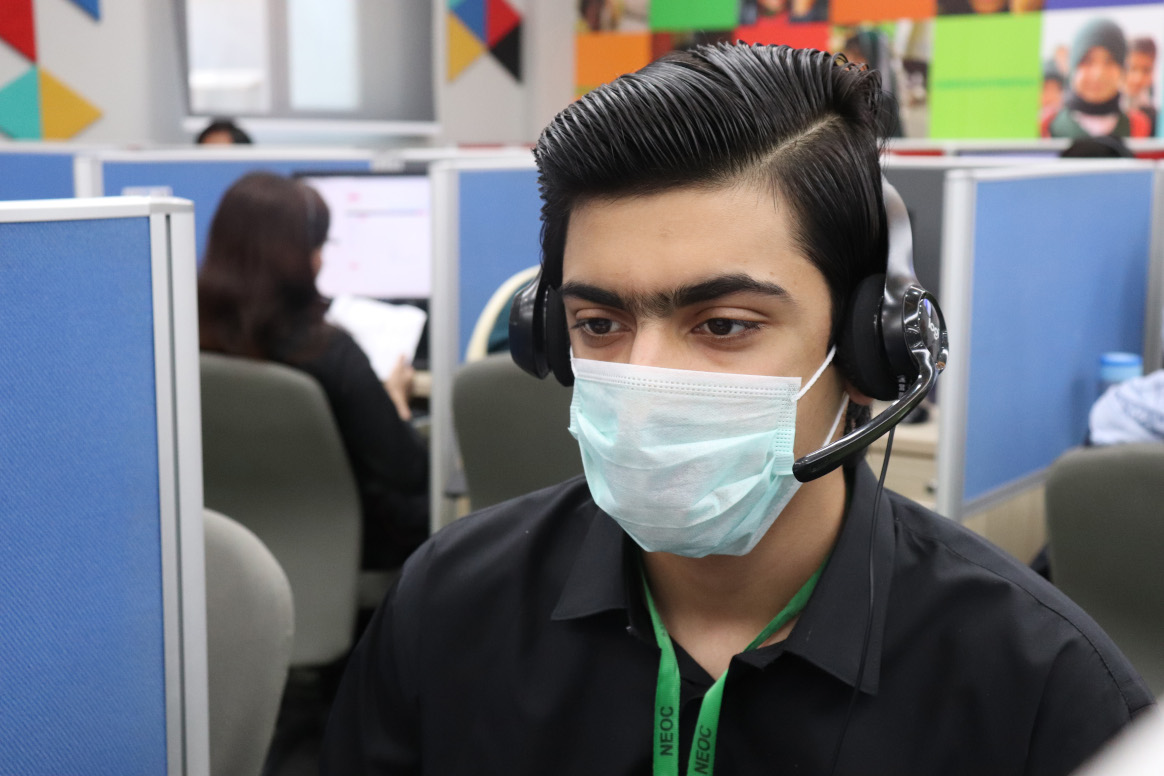

“How can I help you?” Pause. “Have you travelled out of the country recently?” Pause. “Please stay on the line. I am connecting you to a doctor,” says a young woman reassuringly to someone at the other end of the line.

The call operator works at the ‘Sehat Tahaffuz 1166’ COVID-19 Helpline Centre at the National Emergency Operations Centre (NEOC) for Polio Eradication in Islamabad, Pakistan.

Until last month, Sehat Tahaffuz 1166 was a polio eradication helpline to help caregivers share concerns and receive accurate information about polio and other vaccines. As the pandemic spread, the Government expanded the centre to fight COVID-19.

A vital support system during a difficult time

Like many other countries, the global outbreak of COVID-19 poses an enormous challenge to health services in Pakistan. The Sehat Tahaffuz 1166 call centre is increasingly becoming an important platform to listen to the concerns of people, provide correct information, and connect them to a doctor when required.

“I received a phone call from a 75-year-old man this morning. He was so scared and confused because of the coronavirus situation. He asked if sunbathing could help him stay protected from the virus,” said Sadia Saleem, a 24 year old helpline agent. “I explained to him the symptoms of the virus, and the preventive measures. He seemed relieved and thanked me,” she added.

Sadia is one of the 55 call agents currently supporting the helpline, which operates in shifts, from 8am to midnight every day, seven days a week.

“I’ve been working for the 1166 helpline since its inception. It’s stressful work but I feel proud that I’m serving the people during this challenging time. In addition to receiving reliable information, I think most people feel some comfort just speaking with someone from the health system,” said Sadia of her experiences.

Alongside the agents, the government has assigned six doctors to support the Helpline. Dr. Rabia Basri is one of them.

“I am forwarded calls that are critical and need expert medical advice. Every day, I receive about forty calls, some twenty minutes long. These are difficult times for everyone. I often advise people about personal hygiene and physical distancing, and if they are having symptoms, help connect them with a hospital for the coronavirus test and further medical support,” said Dr. Rabia.

70,000 calls a day

“Initially, we were receiving about a thousand calls a day. During the National Polio Immunization Campaign in February 2020 for example, people were calling to report missed children, clarify doubts about vaccines and lodge complaints when health and vaccine services were not working,” said Huma Shaukat, the Helpline Liaison Officer.

However, since the outbreak of COVID-19, the call volume has increased dramatically, to about 70,000 calls a day.

“Each call agent responds to about 150 callers a day. To increase the capacity of the helpline, thirty more agents have joined to manage the growing number of calls,” added Huma.

Despite adding more agents, the call volume has become unmanageable for the helpline centre. The situation has prompted the government to assign additional resources. The Digital Pakistan initiative of the Prime Minister’s Office is helping recruit an additional 165 agents while the National Institute of Health is assigning ten more doctors to the technical team.

Managing the 1166 helpline centre

“Training and commitment of call agents are very important. Otherwise the helpline will not work,” said Huma. “We have four supervisors managing the team of call agents and support them when required as the work here is highly challenging, especially now with the high number of calls every day.”

All call agents undergo a comprehensive training on COVID-19 basic information and primary symptoms facilitated by the National Institute of Health, followed by sessions on the helpline technology and interpersonal communication.

“We generate a daily report and share with relevant sections and the helpline management team. This is very important as it helps us review and manage problems, to continue functioning as an efficient helpline supporting people in their time of need,” Huma explained.

With the leadership of the Government of Pakistan and the support of Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) partners – the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization (WHO) and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), the Sehat Tahaffuz 1166 Helpline has become an essential support system for the people of Pakistan.

“GPEI partners are supporting the Government in utilizing existing polio eradication resources for the COVID-19 response in Pakistan. We are striving together to support as much as we can to ensure the health and safety of all children and families in the country during this challenging time,” said Dennis Chimenya, the UNICEF C4D team lead supporting the helpline in Pakistan.

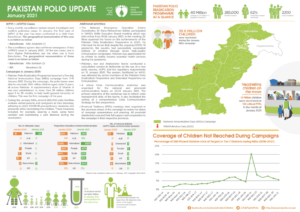

In February

The COVID -19 pandemic response requires worldwide solidarity. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) has a public health imperative to ensure that its resources are used to support countries in their preparedness and response. The COVID-19 emergency also means that polio eradication will be affected. We will continue to communicate on impact, plans and guidance as they evolve.

Urgent updated country and regional recommendations from the Polio Oversight Board – 26 May 2020

| English |

Use of bi-valent Oral Polio Vaccine supplied for polio Supplementary Immunization Activities in Routine Immunization activities | English | French |

Use of oral polio vaccine (OPV) to prevent SARS-CoV2 | English |

Safeguarding in-country mOPV2 stocks during COVID-19 pandemic pause | English |

Polio eradication programme continuity: implementation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic | English | French |

Interim guidelines for frontline workers on safe implementation of house-to-house vaccination campaigns |English| French |

Interim guidance for the polio surveillance network in the context of coronavirus (COVID-19) | English |

This story is also available in other languages: French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese and Spanish

Using the vast infrastructure developed to identify the poliovirus and deliver vaccination campaigns, the polio eradication programme is pitching in to protect the vulnerable from COVID-19, especially in polio-endemic countries. From Pakistan to Nigeria, the programme is drawing on years of experience fighting outbreaks to support governments as they respond to the new virus.

Pakistan

Few health programmes have as much practice tracking virus or reaching out to communities as the Pakistan polio eradication programme. This means the polio team is in a strong position to support the Government of Pakistan in COVID-19 preparedness and response.

Currently, the polio team is providing assistance across the entire country, with a special focus on strengthening surveillance and awareness raising. Working side-by-side with the Government of Pakistan, within three weeks the team has managed to train over 280 surveillance officers in COVID-19 surveillance. It has also supported the development of a new data system that’s fully integrated with existing data management system for polio. All polio surveillance staff are now doubling up and supporting disease surveillance for COVID-19. Through cascade trainings, they have sensitized over 6,260 health professionals on COVID-19, alongside their polio duties, in light of the national emergency. These efforts will continue unabated as the virus continues to spread.

Adding to the capacity of the government and WHO Emergency team, the polio team are also engaged in COVID-19 contact tracing and improving testing in six reference laboratories. They have been trained to support and supplement the current efforts, preparing for a sudden surge in cases and responding to the increase in travelers that need to be traced as a result of the rise in cases. The regional reference laboratory for polio in Islamabad is also providing technical support to COVID-19 testing and has been evolving to cater to the increased demands.

As this is a new disease, polio staff are lending their skills as health risk communicators – providing accurate information and listening to people’s concerns. The government of Pakistan extended a national help line originally used for polio-related calls to now cater to the public’s need for information on COVID-19. The help line was quickly adapted by the polio communication team once the first COVID-19 case was announced. The polio communications team is using strategies routinely used to promote polio vaccines to disseminate information about the COVID-19 virus, including working with Facebook, to ensure accurate information sharing, and airing television adverts. As time goes on, the teams will train more and more people ensuring the provision of positive health practices messages that can curb the transmission of the virus.

Afghanistan

Currently, community volunteers who work for the polio programme to report children with acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) are delivering messages on handwashing to reduce spread of COVID-19, in addition to polio. UNICEF is similarly using its Immunization Communication Network to disseminate information on personal hygiene.

Field staff have taken the initiative of using their routine visits to health facilities, during which they check for children with AFP, to check for and report people who may have COVID-19. Meanwhile, programme staff are building the capacity of health workers to respond to the novel coronavirus.

To coordinate approaches, the WHO Afghanistan polio team has a designated focal point connecting with the wider COVID-19 operation led by the Government of Afghanistan. The polio eradication teams at regional and provincial levels are working closely with the Ministry of Public Health, non-governmental organizations delivering Afghanistan’s Basic Package of Health Services and other partners to enhance Afghanistan’s preparedness.

Nigeria

“In the field, when there is an emergency, WHO’s first call for support to the state governments is the polio personnel,” says Fiona Braka, WHO polio team lead in Nigeria.

In Ogun and Lagos states, where two cases of COVID-19 have been detected, over 50 WHO polio programme medical staff are working flat out to mitigate further spread, using lessons learnt from their years battling the poliovirus. Staff are engaged in integrated disease surveillance, contact tracing, and data collection and analysis. Public health experts working for the Stop Transmission of Polio programme, supported by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, are using their skills to undertake COVID-19 case investigations.

The WHO Field Offices -which are usually used for polio eradication coordination- are doubling up as coordination hubs for WHO teams supporting the COVID-19 response. The programme is also lending phones, vehicles and administrative support to the COVID-19 effort.

In states where no cases of COVID-19 have been reported, polio staff are supporting preparedness activities. At a local level, polio programme infrastructure is being used to strengthen disease surveillance. Polio staff are working closely with government counterparts and facilitating capacity building on COVID-19 response protocols and are working to build awareness of the virus in the community. Specials efforts are being undertaken to train frontline workers as they are at high risk of contagion.

Beyond polio-endemic countries

Trained specialists in the STOP program, part of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, are actively supporting preparations or response to COVID-19 in 13 countries worldwide. The WHO Regional Office for Africa’s Rapid Response Team, who usually respond to polio outbreaks, are aiding COVID-19 preparedness in countries including Angola, Cameroon and the Central African Republic. Meanwhile, polio staff in other offices are ready to lend support, or are already lending support, to colleagues working to mitigate and respond to the new virus.

In our work to end polio, the programme sees the devastating impact that communicable diseases have. With this in mind, we are fully committed to supporting national health systems by engaging our expertise and assets to help mitigate and contain the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside continuing concerted efforts to eradicate polio.

For the latest information and advice on the COVID-19 disease outbreak visit the WHO website.

Thousands of women work in the Pakistan polio eradication programme as scientists of many specialties, managers, data experts, vaccinators, front-line team supervisors and social mobilizers. We asked a few of them about gender equality in their work.

Dr. Maryam Mallick: The Medical Rehabilitation Specialist

“Women face extra difficulties in trying to prove themselves and often compete in an outnumbered male dominated work environment. But with the right support, they persevere and excel in their tasks.”

Dr. Maryam Mallick is one of the first female technical advisors for disability and rehabilitation at the World Health Organization in Pakistan. Her job involves assessing children with polio paralysis to ensure that they receive medical and social rehabilitation care.

Dr. Mallick works to ensure that all children, especially girls, are given access to quality healthcare as well as equal opportunities in society.

“There were many instances where parents did not want their polio affected daughters to be sent to the schools. We need to start perceiving gender equality as a fundamental human right inherently linked to sustainable development, rather than just a women’s issue,” she says.

“Women’s empowerment in achieving sustainable development has now been globally recognized as the centrality of gender equality. It does not mean that men and women become the same, rather it means that everyone can have equal rights and equal opportunities”

Under Dr. Mallick’s supervision, one thousand children have been assisted by the Polio Rehabilitation Initiative since 2007.

Dr. Iman Gohar: The first female Provincial Rapid Response Unit Lead in Sindh province

“Many women in the programme have enormous talent and endless potential. These women are key to enabling success across the polio eradication effort.”

Dr. Iman Gohar joined the Pakistan polio eradication programme six years ago, working as a Polio Eradication Officer in Peshawar and then as the Divisional Surveillance Officer in Hyderabad. Today, Dr. Gohar is the first woman to lead the Provincial Rapid Response Unit in Sindh.

Dr. Gohar’s work involves leading investigations into suspected polio cases and organising case response campaigns. An increased number of environmental samples found positive for the poliovirus in Sindh in the 2019-2020 period has meant a busy workload.

“Polio eradication is an incredibly demanding job. I work for long hours and enjoy one day off in the week. While performing my job, I work hard to take complex goals and convert them into high quality deliverables,” she says.

“The programme has provided women with a very conducive environment to grow, learn and voice their opinion. For this, I am very grateful.”

When talking about how the programme can improve gender equality, Dr. Gohar stressed the role and support of her male colleagues.

“I believe for us to achieve true gender equality, it is essential that our male co-workers become advocates for equality. Men and women must both hold each other up, celebrate each other’s successes and recognize that each and every person, regardless of gender, is playing an important role in safeguarding the health of Pakistan’s children.”

Salma Bibi: A Health Worker in Killa Abdulla district, Balochistan province

“Nothing gives me greater satisfaction than knowing how I have helped people through my duties. I believe that creating opportunities for women is one of the best ways to empower them.”

Salma has been a community health worker for over a decade, working in Killa Abdullah district in Balochistan province. Around 90% of the district is overseen by male health workers, so Salma is one of the few women who go door to door to ensure that children are vaccinated.

Salma often feels greater resistance from community members than her male counterparts. “I hear a lot of negative comments from community members, especially when covering vaccine hesitant families. These words can sometimes de-motivate and de-moralize us from our duties,” she says.

Despite this challenging environment, Salma recognizes that her role is integral to get parents to understand the importance of vaccination.

“When our male colleagues cannot enter the homes, we play an important role in filling that gap. We go in and we sit with the mothers to help them understand that vaccinating against polio is the only way to protect their children. Often, the time spent talking to them is enough, and this makes us feel good, like we are truly helping our nation’s children.”

Saba Irshad: The first female Programme Data Assistant in Multan district, Punjab province

“The greatest challenge that the majority of the professional women face is the perception that they are not as qualified or competent as their male colleagues, irrespective of their experience, education, potential or achievements. Because of this, women often have to work twice as hard.”

Saba Irshad has worked with the Pakistan polio eradication programme for eight years. She is known by her colleagues for her quick problem-solving skills and meticulous work. As a Programme Data Assistant, Saba is responsible for collecting and analyzing data from campaigns implemented in Multan district, in Punjab province.

Saba emphasizes the need for the polio programme to continue to support and encourage their female workforce, and promote an inclusive work environment.

“On average, 62% of the vaccinator workforce in Pakistan are women. This shows just how important women are to polio eradication.”

“Without these women, the programme would be unable to reach thousands of children with the vaccine.”

To learn what the Global Polio Eradication Initiative is doing to promote gender equality, visit the gender section of our website.

Dr Faten Kamel is on a flying visit to the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Regional Hub, stopping for meetings and to deliver a lecture on the relationship between polio and patients with primary immunodeficiencies. Then she’s off again – to Pakistan to take part in a polio programme management review.

Dr. Faten has travelled to every country in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, and many more besides. Alongside working as a Senior Global Expert for the programme, she is a wife, a mother, grandmother, and an informal mentor to women in public health.

Growing up in Alexandria, Egypt, Dr. Faten was exposed to the life-altering effects of polio on the people around her and was inspired by the work of her father, a surgeon and a Rotarian.

“My father was my role model, he had great passion for helping others and was also a Rotary Club president in 1989. His project for that year was on polio eradication.”

“Polio was prevalent in Egypt in those days. A number of people around me were affected. I was touched by their suffering in a place which was not highly equipped for people with special needs at that time.”

Making rapid gains against polio

After graduating from her Medical Degree and Doctorate in Public Health, and lecturing for several years at Alexandria University, Dr. Faten moved into a role for WHO. She found her niche working in the immunization team. “Immunization is the most cost effective public health tool – it can prevent severe and deadly diseases with just two drops or a simple injection – I strongly believe in preventive medicine,” she explains.

“I became the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Medical Officer for polio eradication in 1998. At that time many countries were still endemic.”

The 1990s and early 2000s were years of rapid gains against the virus. However to fully eradicate polio, it was becoming clear that the programme would have to be more ingenious than any disease elimination or eradication project that had come before.

Dr. Faten took a leading role. She explains, “Strategies for immunization and disease surveillance were established, and these methods evolved over time. We pushed the boundaries to make the programme more effective – shifting to house to house vaccination, detailed microplanning and mapping, retrieval of missed children and independent monitoring.”

“We started as a small team – covering different aspects of work and supporting all the countries. My team started the regular analysis and publishing of data in “Poliofax”, we supported the shift to case based and active surveillance and gradually added different supplementary activities including environmental surveillance.”

“I was blessed to have the support of my parents, my husband and my son. As a married woman I think it is very important to have the support of your family. I also had wonderful supervisors who believed in my capabilities and gave me opportunities. I am similarly impressed with many of the young women in the programme today.”

Overcoming outbreaks

Sometimes the biggest challenges for Dr. Faten and her team came out of the blue, such as when the programme faced huge polio outbreaks in areas that had become free of the virus.

“We didn’t expect polio to cause large outbreaks, but we were faced with them. To overcome the situation we started to work together as partners on effective response strategies within and across regions. The virus does not stop at borders and we had to coordinate multi-country activities.”

“In the polio eradication programme we cannot be satisfied with 80% or 90% coverage – we need to reach each and every child no matter where they are, even in the hard to reach and insecure places. So there was always a lot of innovation and adaptive strategies, we were thinking how can we bridge this, and reach these children.”

“That’s how we came up with access analysis and negotiation, days of tranquility, using windows of opportunities and short interval campaigns, community involvement and collaboration with NGOs, intensifying work at exit points, thinking out of the box all the time.”

Tracking polio down unexpected paths

Dr. Faten was determined to possess firsthand information on polio cases, no matter where they occurred. Sometimes, this led her down unexpected paths – such as when she travelled 21 hours through the Sudanese bush to track down a polio case in a remote village.

“I’ll never forget when a wild poliovirus type 3 (WPV3) case appeared in a very faraway place in Sudan after years without WPV3. I said, “I have to see it myself”. This mission was one of my most challenging fieldtrips.”

“We faced many difficulties, it was the rainy season, the car slipped on its side on our way and we arrived after midnight.”

“I thought the virus must have been hiding in this place for years. But I found the disease surveillance to be very good. Then by investigating, we found there was a wedding, and relatives were coming from another province, so I could nearly point my finger to where the virus came from. The virus was detected in that area and we managed to curtail its spread.

A career spent getting ahead of the virus

In 2016, Dr. Faten set up the Rapid Response Unit in Pakistan – a dedicated ‘A team’ that can jump into an at-risk area to mitigate virus spread. Today, she is working with medical professionals to ensure that individuals with primary immunodeficiencies get tested for poliovirus, as some of them are at risk of prolonged virus shedding.

What keeps her awake at night?

“I care about where we are not reaching. Polio eradication is beyond health – it needs all the sectors to come together especially in a big country. In the last strongholds of the virus we have population movement across the border, some areas that are difficult to reach, and there are some misconceptions.”

“If someone comes and says this area is inaccessible, this is not an answer for me. I ask: What should we do to reach? I like to make use of the ideas and experience that come from local people. The virus strongholds are in certain areas, so let us work closely with the people in these areas, empower them, and allow them to change the situation.”

Dr Faten is proud to be part of the polio eradication programme and looks forward to the day when polio eradication is achieved, so she can spend more time with her family in Australia.

“As a grandmother, I am especially determined to finish the job. I want my grandkids to grow up in a world free of polio. This will be my contribution to their futures.”

The Secretary-General of the United Nations (UNSG) António Guterres yesterday visited a kindergarten school in Lahore during the first nationwide polio campaign of the year and vaccinated students with the polio vaccine. More than 39 million children across the country are set to be vaccinated during the February campaign.

The UNSG commented on the polio eradication efforts of the country, saying that, “Polio is one of the few diseases we can eradicate in the world in the next few years. This is a priority of the United Nations and I am extremely happy to see it is a clear priority for the Government of Pakistan.”

“My appeal to all leaders, religious leaders, community leaders, is to fully support the Government of Pakistan and other governments around the world to make sure that we will be able to fully eradicate polio.”

As part of his visit, Secretary-General Guterres met with frontline workers of the Pakistan Polio Eradication Programme and expressed his deep solidarity. There are currently 265,000 frontline workers who go door to door during campaigns to ensure that as many children as possible are vaccinated against polio. Almost 62% of these workers are female. Women are key to helping the programme rally community members, parents and caregivers in support of polio eradication.

Dr. Yasmin Rashid, the Health Minister for Punjab, welcomed Secretary-General Guterres to the school. Dr. Rashid briefed the UN mission on Pakistan’s progress in polio eradication, the remaining challenges faced by the country, and strategies being currently implemented to interrupt virus transmission. She further praised the efforts of the United Nations in assisting Pakistan to achieve a polio-free status.

“The Government of Pakistan thanks the United Nations for their support and commitment to end Pakistan’s battle against polio. We are committed to working as ‘one team under one roof’ and believe together, we can make Pakistan polio-free,” Dr. Yasmin Rashid said.

In 2019, Pakistan was confronted with a resurgence of polio beyond traditional strongholds of the virus. Wild poliovirus cases increased from 12 in 2018 to 144 by the end of 2019. There are 17 cases thus far in 2020. Secretary-General Guterres’ visit comes at a time when the Pakistan Polio Eradication Programme is re-thinking its operations to better respond to increased virus transmission.

WHO Pakistan Representative Dr Palitha Malipala emphasized the importance of incorporating high level commitment to polio eradication from across the political strata.

“Polio eradication remains a top priority for WHO and the global polio partnership. We will continue to support the Government of Pakistan, who spearhead this initiative in country, to overcome the challenges of the last year and put in place robust measures to ensure a polio-free world for future generations,” he said.

There is a long-standing relationship between the Global Polio Eradication Initiative and the Office of the UN Secretary-General. Two previous UNSGs – Kofi Annan and Ban Ki-Moon – were both strong advocates of global polio eradication as an important goal of the UN system. Secretary-General Guterres’ visit continues this collaboration and emphasizes his personal oversight and commitment to a polio-free world.

Pakistan and Afghanistan are the only countries worldwide where wild poliovirus is still endemic. The concerted commitment to improving operations shown by both countries will be key to eradicating the virus.