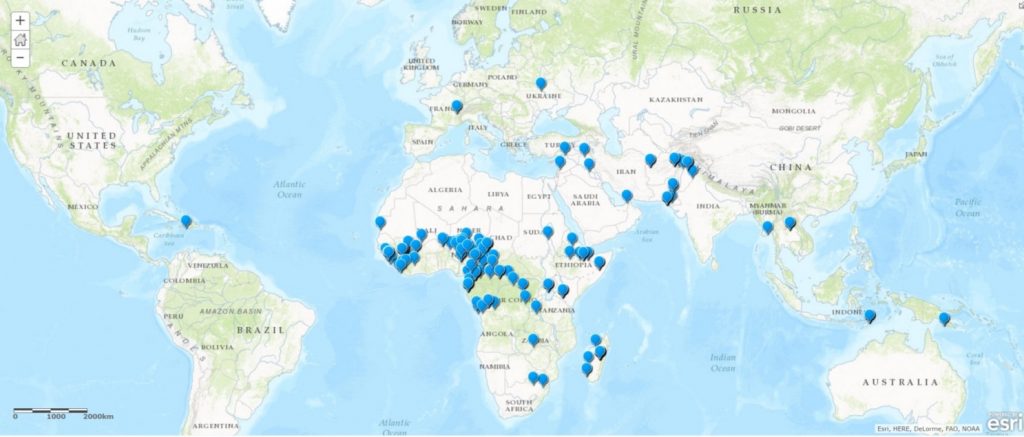

The nomads of the Lake Chad Basin account for 3%–5% of the population and are one of the most underserved communities when it comes to health.

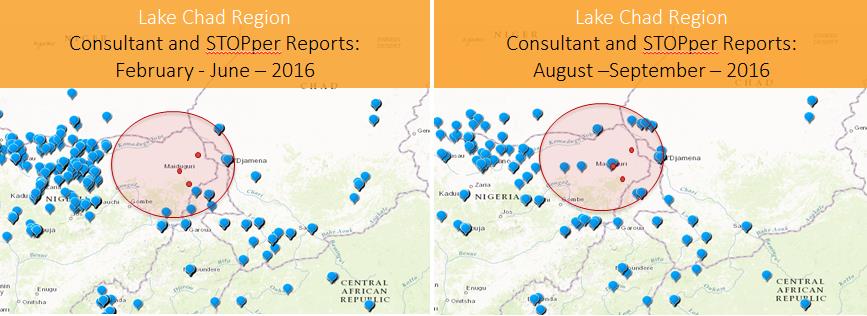

When Chad had to respond to the detection of wild poliovirus in Nigeria in 2016, it was crucial to vaccinate nomadic children. The World Health Organization, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and partners created a database of population numbers, movements, and immunization records. ‘Lake Chad response teams’, each with four specialists – an epidemiologist, a social mobilizer, a vaccinator and a data recorder – fanned out, data in hand, to reach every nomadic child with polio vaccines.

Often teams began by speaking to nomads in a market or on a road and then asking to follow them to their temporary camp. The Lake Chad Basin covers almost 8% of the African continent and trying to find groups amongst the vast expanse of semi-arid savannah was almost impossible without this kind of time-consuming work.

Upon arriving in a camp, the social mobilizer in each response team explained to family elders and parents the purpose of the vaccination and the benefits for their children. The response teams asked for permission to begin vaccination.

“They see themselves as neglected in society,” explains Ajiri Okpure Atagbaza, a GIS consultant in the WHO Regional Office for Africa Geographic Information System Centre, who spent three years as part of the Chad response team working with nomads. “When you came with aid, they welcomed you. As long as you spoke their language, they were open to it.”

Children received all immunizations for their age alongside polio vaccine, as part of an integrated approach to health delivery. The parents were given an immunization card recording which vaccines had been administered.

Each team carried a smartphone application used to capture the locations of the nomadic camps, the results of acute flaccid paralysis case surveillance, and information gained through conversations with the community, such as how long they had been in their current location, previous and future camp locations, the population size and vaccination rates. This information was uploaded to bolster the database to help plan future health services.

From April to August 2019, the Lake Chad response teams reached 1067 nomad groups in 17 districts in Chad alone and vaccinated more than 27,000 children. Across all five countries making up the Basin, more than 40,000 children in 3451 nomadic camps in 62 high-risk districts received their routine immunizations, including protection against polio. The information recorded during these activities will be used in routine immunization planning to ensure that children continue to receive all their vaccinations according to the schedule.